“These stars aren’t really there anymore, are they?”

I’ve frequently heard the same question from observatory visitors since 1982, whether at my own observatories, at the Storm King Academy where I taught, at the famous Millbrook School where I gave astro lectures, and elsewhere in these dark mountains of upstate New York.

I respect that question, even though the logic behind it isn’t correct. It reveals awareness that light has a finite speed and that we might see an image even if a star no longer exists. But the thinking is wrong because the 6,000 naked-eye stars have an average lifespan of over a billion years apiece, and their images’ travel time to Earth never exceeds a few thousand years. I’ve calculated roughly 200-to-1 odds that not even one of the night’s visible stars has died in the brief time its image was en route.

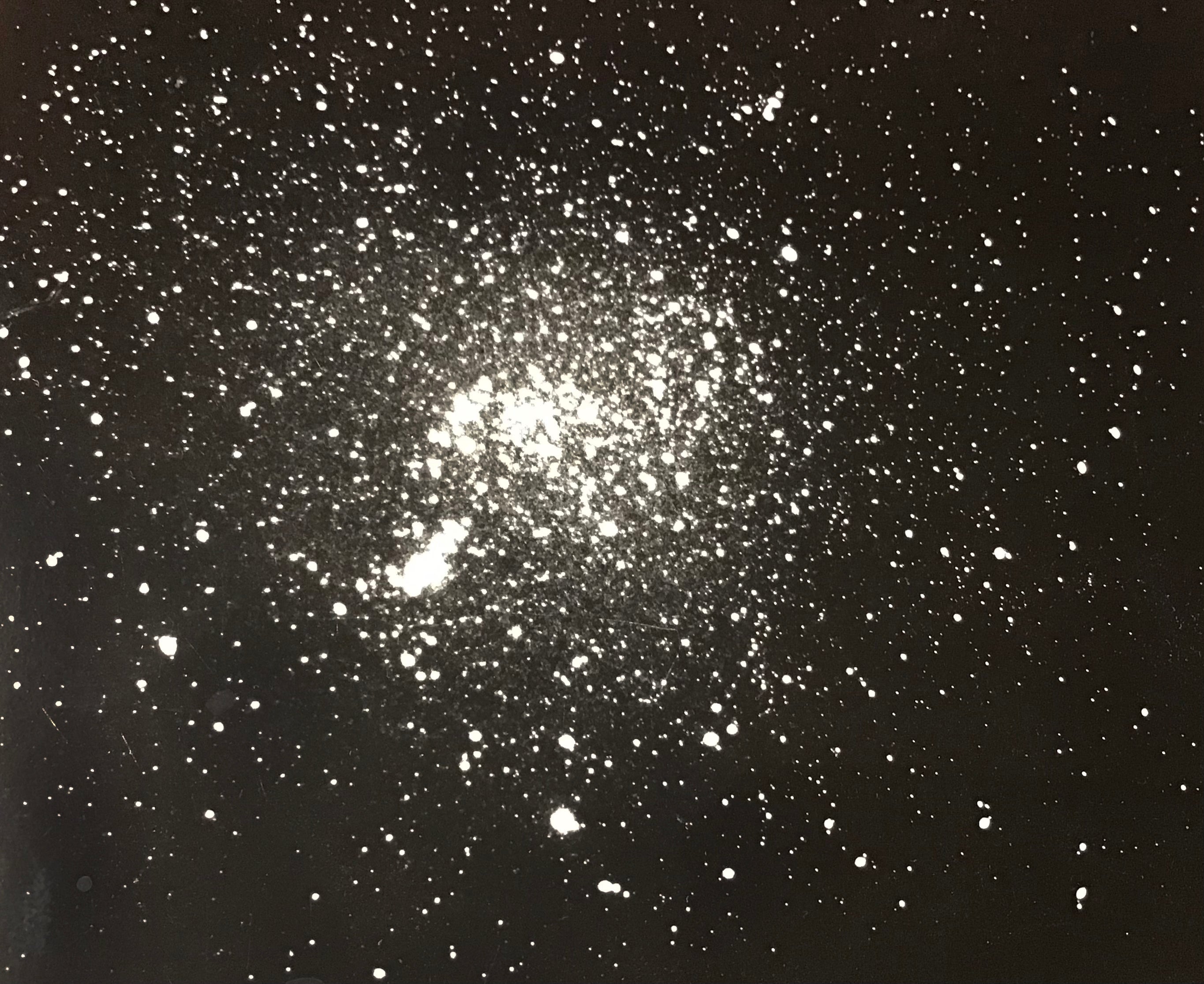

Seeking what’s real keeps us uncovering surprises and complexities. On this page is a photo I took four decades ago, of the constellation Orion. It appears as one big star cluster because the gas-hypered film I used was insensitive to the red nebulosity that wreaths that constellation and instead emphasized the star cluster centered on the Hunter’s belt. A different photographic technique would eighty-six the cluster while making the nebulosity pop out. And when viewed with the naked eye at a typical suburban site, Orion appears as neither a cluster nor a nebula, but as the familiar hourglass pattern of its brightest stars.

One takeaway, then, is that observers might want to be more open-minded about what’s “really there.”

A famous reality issue involves quantum theory. Physicists mostly disbelieve that objects exist with specific properties when no one observes them. Yet, do you know any astronomer who thinks the Moon’s not there when nobody’s viewing it? Albert Einstein used this exact example when questioning physicist Abraham Pais.

Another issue is an obsession of Canadian physicist Roy Bishop, with whom I sometimes correspond. He believes — as was also believed by Isaac Newton — that there are no colors in the universe. Instead, Bishop insists that external color is an illusion that afflicts 99.9 percent of all scientists and laypeople.

A common misapprehension is that our pupils and lenses are like clear windows letting in colors that, when detected by our retina’s cone cells, allow us to experience the supposedly multihued universe. In truth, the Moon’s reflected sunlight is solely composed of alternating magnetic and electrical fields. Though we are blind to these fields, their electromagnetic energy does excite retina cells to stimulate physiological architecture in the brain’s occipital lobe. There, hundreds of millions of neurons create the conscious experience of brightness and color.

But human vision is evolutionarily motivated by individual survival and species preservation, so this process has no reason to accurately replicate the full external world. So when we see the lovely emerald glow of the Cat’s Eye Nebula (NGC 6543), its green is no more “really there” than if we experienced Mars smelling like bacon. In fact, nature could have just as easily constructed our brains to make us perceive the Cat’s Eye as the aroma of a BLT with no color accompaniment whatsoever. That’s because colors are not external phenomena, but creations happening entirely within the skull.

Newton emphasized this some three centuries ago. It’s too bad astronomers aren’t more aware of visual physiology; perhaps they would then truly appreciate why a lunar eclipse looks reddish only when totality is approaching, as our Moon is bathed in increasingly longer wavelengths of electromagnetic radiation. These wavelengths are manifested by the physiological response of creating and experiencing redness, which very much involves our biological selves. Red in particular is a tricky hue to perceive: We are blind to it at low light levels, which is why average backyard scopes don’t show M42’s abundant reds. Lunar totality is the only celestial sight in which the brightness level is sufficient to stimulate our red-light-sensing cells into producing a major experience of nocturnal color vision.

Regardless of the reason why, we’ll keep enjoying our gorgeous visual astro-experiences even when they’re as real as laughter in a dream. They deliver pleasure and knowledge. But before we lecture anybody on what’s really there, we might take a deep breath, for we’re still toddlers in a playpen of surprises.