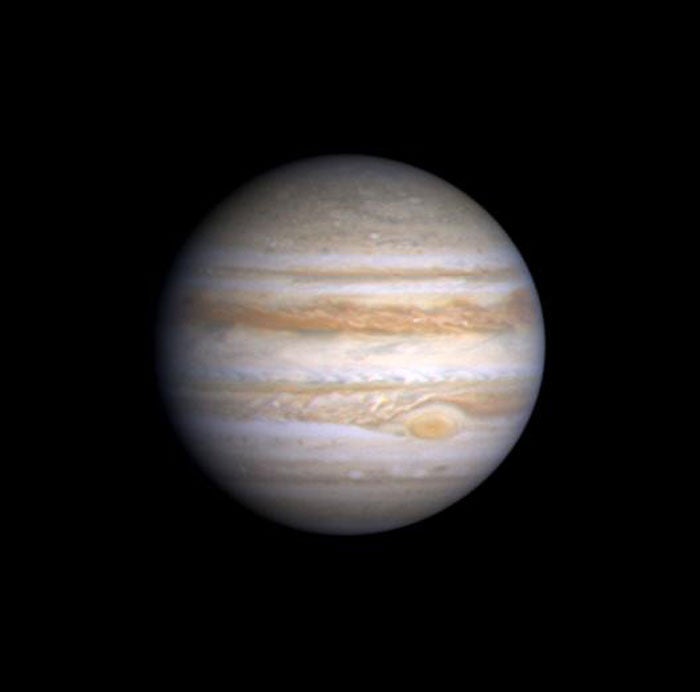

Earlier this year, amateur astronomers noticed that a long-standing dark-brown stripe, known as the South Equatorial Belt, just south of Jupiter’s equator, had turned white. In early November, amateur astronomer Christopher Go of Cebu City, Philippines, saw an unusually bright spot in the white area that was once the dark stripe. This phenomenon piqued the interest of scientists at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) in Pasadena, California, and elsewhere.

After follow-up observations in Hawaii with NASA’s Infrared Telescope Facility, the W.M. Keck Observatory, and the Gemini Observatory telescope, scientists now believe the vanished dark stripe is making a comeback.

“The reason Jupiter seemed to lose this band — camouflaging itself among the surrounding white bands — is that the usual down-welling winds that are dry and keep the region clear of clouds died down,” said Glenn Orton from JPL. “One of the things we were looking for in the infrared was evidence that the darker material emerging to the west of the bright spot was actually the start of clearing in the cloud deck, and that is precisely what we saw.”

This white cloud deck is made up of white ammonia ice. When the white clouds float at a higher altitude, they obscure the missing brown material, which floats at a lower altitude. Every few decades or so, the South Equatorial Belt turns completely white for perhaps 1 to 3 years, an event that has puzzled scientists for decades. This extreme change in appearance has only been seen with the South Equatorial Belt, making it unique to Jupiter and the entire solar system.

The white band wasn’t the only change on the big, gaseous planet. At the same time, Jupiter’s great red spot became a darker red color. Orton said the color of the spot — a giant storm on Jupiter that is 3 times the size of Earth and a century or more old — will likely brighten a bit again as the South Equatorial Belt makes its comeback.

The South Equatorial Belt underwent a slight brightening, known as a “fade,” just as NASA’s New Horizons spacecraft was flying by on its way to Pluto in 2007. Then there was a rapid revival of its usual dark color 3 to 4 months later. The last full fade and revival was a double-header event, starting with a fade in 1989, revival in 1990, then another fade and revival in 1993. Similar fades and revivals have been captured visually and photographically back to the early 20th century, and they are likely to be a long-term phenomenon in Jupiter’s atmosphere.

Scientists are particularly interested in observing this latest event because it’s the first time they’ve been able to use modern instruments to determine the details of the chemical and dynamical changes of this phenomenon. Observing this event carefully may help refine the scientific questions to be posed by NASA’s Juno spacecraft, due to arrive at Jupiter in 2016, and a larger proposed mission to orbit Jupiter and explore its satellite Europa after 2020.

The event also signifies another close collaboration between professional and amateur astronomers. The amateurs, located worldwide, are often well equipped with instrumentation and are able to track the rapid developments of planets in the solar system. These amateurs are collaborating with professionals to pursue further studies of the changes that are of great value to scientists and researchers everywhere.

“I was fortunate to catch the outburst,” said Christopher Go, referring to the first signs that the band was coming back. “I caught the outburst just in time as it was rising. Had I imaged earlier, I would not have caught it.” Go witnessed the disappearance of the stripe earlier this year, and in 2007 he was the first to catch the stripe’s return. “I was able to catch it early this time around because I knew exactly what to look for.”

Earlier this year, amateur astronomers noticed that a long-standing dark-brown stripe, known as the South Equatorial Belt, just south of Jupiter’s equator, had turned white. In early November, amateur astronomer Christopher Go of Cebu City, Philippines, saw an unusually bright spot in the white area that was once the dark stripe. This phenomenon piqued the interest of scientists at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) in Pasadena, California, and elsewhere.

After follow-up observations in Hawaii with NASA’s Infrared Telescope Facility, the W.M. Keck Observatory, and the Gemini Observatory telescope, scientists now believe the vanished dark stripe is making a comeback.

“The reason Jupiter seemed to lose this band — camouflaging itself among the surrounding white bands — is that the usual down-welling winds that are dry and keep the region clear of clouds died down,” said Glenn Orton from JPL. “One of the things we were looking for in the infrared was evidence that the darker material emerging to the west of the bright spot was actually the start of clearing in the cloud deck, and that is precisely what we saw.”

This white cloud deck is made up of white ammonia ice. When the white clouds float at a higher altitude, they obscure the missing brown material, which floats at a lower altitude. Every few decades or so, the South Equatorial Belt turns completely white for perhaps 1 to 3 years, an event that has puzzled scientists for decades. This extreme change in appearance has only been seen with the South Equatorial Belt, making it unique to Jupiter and the entire solar system.

The white band wasn’t the only change on the big, gaseous planet. At the same time, Jupiter’s great red spot became a darker red color. Orton said the color of the spot — a giant storm on Jupiter that is 3 times the size of Earth and a century or more old — will likely brighten a bit again as the South Equatorial Belt makes its comeback.

The South Equatorial Belt underwent a slight brightening, known as a “fade,” just as NASA’s New Horizons spacecraft was flying by on its way to Pluto in 2007. Then there was a rapid revival of its usual dark color 3 to 4 months later. The last full fade and revival was a double-header event, starting with a fade in 1989, revival in 1990, then another fade and revival in 1993. Similar fades and revivals have been captured visually and photographically back to the early 20th century, and they are likely to be a long-term phenomenon in Jupiter’s atmosphere.

Scientists are particularly interested in observing this latest event because it’s the first time they’ve been able to use modern instruments to determine the details of the chemical and dynamical changes of this phenomenon. Observing this event carefully may help refine the scientific questions to be posed by NASA’s Juno spacecraft, due to arrive at Jupiter in 2016, and a larger proposed mission to orbit Jupiter and explore its satellite Europa after 2020.

The event also signifies another close collaboration between professional and amateur astronomers. The amateurs, located worldwide, are often well equipped with instrumentation and are able to track the rapid developments of planets in the solar system. These amateurs are collaborating with professionals to pursue further studies of the changes that are of great value to scientists and researchers everywhere.

“I was fortunate to catch the outburst,” said Christopher Go, referring to the first signs that the band was coming back. “I caught the outburst just in time as it was rising. Had I imaged earlier, I would not have caught it.” Go witnessed the disappearance of the stripe earlier this year, and in 2007 he was the first to catch the stripe’s return. “I was able to catch it early this time around because I knew exactly what to look for.”