The nearby or “local” universe — an area that extends about 380 million light-years away — contains many galaxy clusters, i.e., gravitationally bound groups of about 100 to more than 1,000 galaxies. These clusters are connected with each other and make up a huge network of galaxies called the “large-scale structure” of the universe. Such configurations raise fundamental questions: When and how did these structures form in the history of the universe?

Astronomers think the universe started out as an almost homogeneous mass that spread uniformly. Small fluctuations in the initial mass distribution increased by gravity over the 13.7 billion years of the universe’s age and produced the recent array of clusters. Because clusters contain a larger number of old and massive galaxies than those found in isolated galaxies, astronomers speculate that developing clusters may significantly affect the evolution of their member galaxies. Therefore, understanding the details of cluster formation is an essential step in addressing key issues of structure formation and galaxy evolution. A necessary part of this process is an investigation of all stages of cluster formation from beginning to end, which is why the current team gave particular emphasis to studying the birth of clusters.

The team focused on this phase of cluster formation by searching distant galaxies that existed in the early universe. Such observations present challenges for a couple of reasons. First, the light from more distant galaxies is faint and difficult to detect. Second, protoclusters in the early universe are rare. The use of the Subaru Telescope allowed the team to overcome these difficulties. The telescope not only has an 8.2-meter primary mirror with large light-gathering power, but also offers the advantage of the Subaru Prime Focus Camera (Suprime-Cam) with a wide-field imaging capability. These features are particularly beneficial for discovering faint and rare objects in the distant universe.

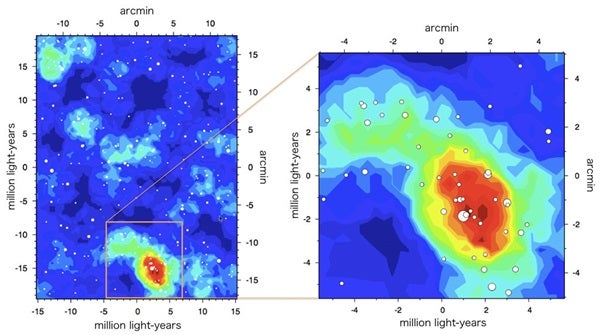

The team chose to observe the Subaru Deep Field, a 0.25-square-degree-wide field in the northern sky near the constellation Coma Barenices. The Subaru Deep Field is one of the most suitable regions for finding protoclusters in the early universe. The area not only is deep and wide, but also has been intensively observed with the Subaru Telescope, which has detected faint galaxies. When the team searched for distant galaxies in the Subaru Deep Field and investigated their distribution, they found a region with a surface number density five times greater than the average.

The astronomers then used Subaru’s Faint Object Camera and Spectrograph (FOCAS) to conduct a spectroscopic observation, which confirmed that most of the galaxies located in the highly dense region lie in a narrow area in the line of sight. This concentration of galaxies could not be explained by chance. On the basis of their observations with the Subaru Telescope, the team confirmed the existence of a protocluster 12.72 billion years ago — the most distant protocluster found with its distance established by spectroscopic observations. The astronomers were able to directly observe this cluster of galaxies at an early stage in galaxy evolution when structures were beginning to form in the early universe. This discovery will be an important step on the way to understanding structure formation and galaxy evolution.

Although the team also investigated the properties of the galaxies in the protocluster, they did not find a significant difference between the protocluster galaxies and other galaxies in the field. The astronomers speculate that the characteristic features of cluster galaxies in the nearby universe occurred in later stages of cluster development, not during their birth. Close examination of the internal structure of the protocluster showed that it could consist of subgroups of galaxies, merging together to form a more massive cluster.

The team will continue their research with the Subaru Telescope’s forthcoming Hyper-Suprime Camera (HSC), which has an imaging capability with a field of view seven times wider than Suprime-Cam. The astronomers expect to use HSC to reveal how many protoclusters existed in the early universe and to provide a better picture of protoclusters in general. “By continually working to find such distant protoclusters, we can understand cluster formation more clearly,” said Toshikawa.