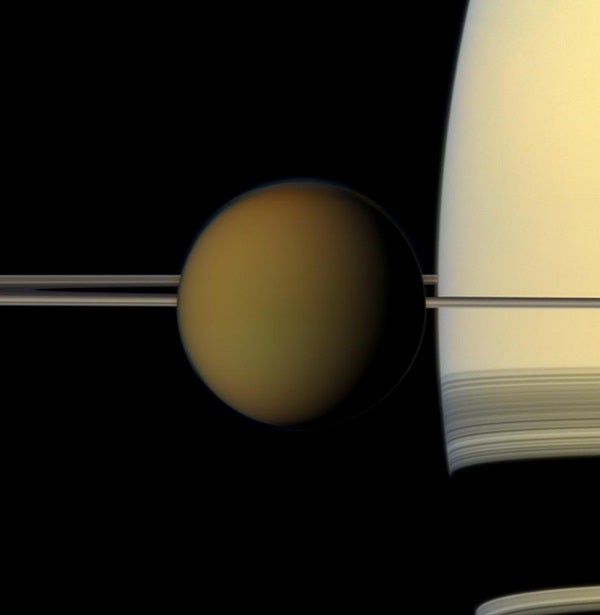

Saturn’s haze-enshrouded moon Titan turns out to have much in common with Earth in the way that weather and geology shape its terrain, according to two pieces of research to be presented at the XXVII General Assembly of the International Astronomical Union (IAU) in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. Wind, rain, volcanoes, tectonics, and other earthlike processes all sculpt features on Titan’s complex and varied surface in an environment more than 212° Fahrenheit (100° Celsius) colder on average than Antarctica.

“It is really surprising how closely Titan’s surface resembles Earth’s,” said Rosaly Lopes, a planetary geologist at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) in Pasadena, California. “In fact, Titan looks more like Earth than any other body in the solar system, despite the huge differences in temperature and other environmental conditions.”

The Cassini-Huygens mission has revealed details of Titan’s geologically young surface, showing few impact craters and featuring mountain chains, dunes, and even “lakes.” The radio detection and ranging (RADAR) instrument on the Cassini orbiter has now allowed scientists to image a third of Titan’s surface using radar beams that pierce the giant moon’s thick, smoggy atmosphere. There is still much terrain to cover, as the aptly named Titan is one of the biggest moons in the solar system, larger than the planet Mercury and approaching Mars in size.

Titan has long fascinated astronomers as the only moon known to possess a thick atmosphere and as the only celestial body other than Earth to have stable pools of liquid on its surface. The many lakes that pepper the northern polar latitudes, with a scattering appearing in the south as well, are thought to be filled with liquid hydrocarbons such as methane and ethane.

“With an average surface temperature hovering around -180°C (-356°F), water cannot exist on Titan except as deep-frozen ice as strong as rock,” Lopes said. On Titan, methane takes water’s place in the hydrological cycle of evaporation and precipitation (rain or snow) and can appear as a gas, a liquid, and a solid. Methane rain cuts channels and forms lakes on the surface and causes erosion, helping to erase the meteorite impact craters that pockmark most other rocky worlds, such as our own Moon and the planet Mercury.

Other new research points to current volcanic activity on Titan, but instead of scorching hot magma, scientists think these “cryovolcanoes” eject cold slurries of water-ice and ammonia. Scientists have spotted evidence for these outflows using another Cassini instrument called the Visual and Infrared Mapping Spectrometer (VIMS). This device can gather the infrared light from the Sun that is reflected back by Titan’s surface after passing through its atmosphere, giving clues about the identity of the chemical compounds found on Titan’s surface.

VIMS had previously detected an area, called Hotei Regio, with a varying infrared signature, suggesting the temporary presence of ammonia frosts that subsequently dissipated or were covered over. Although the ammonia does not stay exposed for long, models show that it exists in Titan’s interior, indicating that a process is at work delivering ammonia to the surface. RADAR imaging has indeed found structures that resemble terrestrial volcanoes near the site of suspected ammonia deposition.

At the IAU General Assembly, new infrared images of this region, with 10 times the resolution of prior mappings, will be unveiled. “These new results are the next advance in this exploration process,” said Robert M. Nelson, a senior research scientist at JPL. “The images provide further evidence suggesting that cryovolcanism has deposited ammonia onto Titan’s surface. It has not escaped our attention that ammonia, in association with methane and nitrogen, the principal species of Titan’s atmosphere, closely replicates the environment at the time that life first emerged on Earth. One exciting question is whether Titan’s chemical processes today support a prebiotic chemistry similar to that under which life evolved on Earth?”

Yet more terrestrial-type features on Titan include dunes formed by cold winds and mountain ranges. These mountains might have formed tectonically when Titan’s crust compressed as it went into a deep freeze, in contrast to the Earth’s crust, which continues to move today, producing earthquakes and rift valleys on our planet.

Many Titan researchers hope to observe Titan with Cassini for long enough to follow a change in seasons. The new image released by JPL shows what appears to be a dried-out lake at Titan’s south pole. Lopes thinks the hydrocarbons there likely evaporated because this hemisphere is experiencing summer. When the seasons change in several years and summer returns to the northern latitudes, the lakes so common there may evaporate and end up pooling in the south.