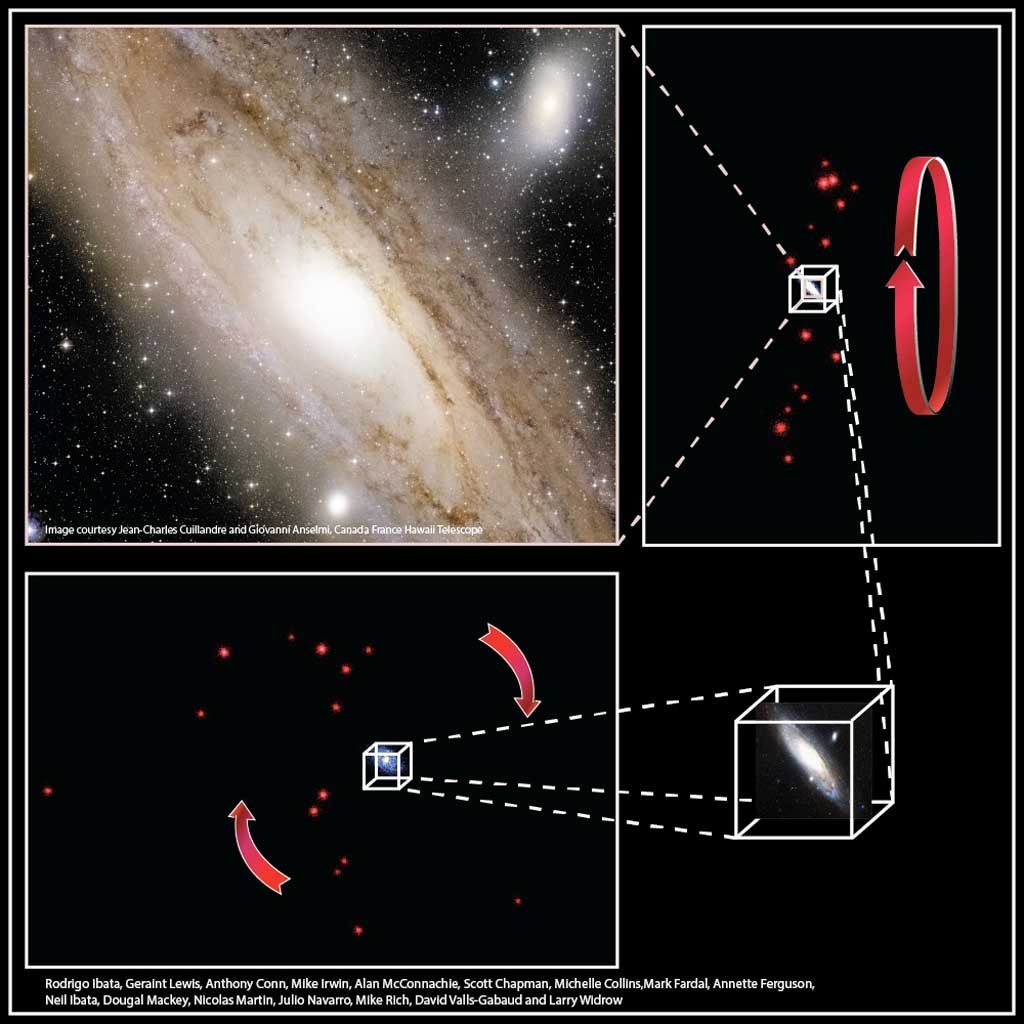

While Persian astronomers were the first to catalog the Andromeda Galaxy, it’s been only in the past five years that scientists have studied in detail the most distant suburbs of the Andromeda Galaxy via the Pan-Andromeda Archaeological Survey (PAndAS), undertaken with the Canada-France-Hawaii Telescope and measured with the Keck Observatory, providing our first panoramic view of our closest large companion in the cosmos.

The study culminates many years of effort by an international team of scientists who have discovered a large number of the satellite galaxies, developed new techniques to measure their distances, and have used the Keck Observatory with colleagues to measure their radial velocities, or Doppler shifts — the speed of the galaxy relative to the Sun. While earlier work had hinted at the existence of this structure, the new study has demonstrated its existence to a high level of statistical confidence — 99.998 percent.

The study reveals almost 30 dwarf galaxies orbiting the larger Andromeda Galaxy in this regular, solar system-like plane. The astronomers’ expectations were that these smaller galaxies should be buzzing around randomly like bees around a hive.

“This was completely unexpected,” said Geraint Lewis from the University of Sydney. “The chance of this happening randomly is next to nothing.” The fact that astronomers now see that a majority of these little systems in fact contrive to map out an immensely large — approximately 1 million light-years across — but extremely flattened structure implies that this understanding is grossly incorrect. Either something about how these galaxies formed or subsequently evolved must have led them to trace out this peculiar coherent structure.

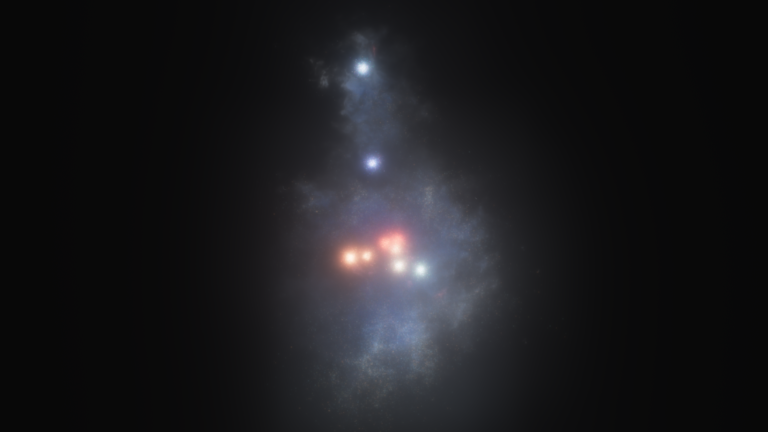

“We know of a number of galaxies that have experienced a collision, causing some of their stars to be expelled great distances, in sheets and tails. However, it’s unlikely that kind of event explains what we are observing,” said R. Michael Rich from the University of California, Los Angeles.

While dwarf galaxies are not massive, they are the most numerous galaxy type in the universe. Understanding this assemblage will undoubtedly shed new insight into the formation of galaxies at all masses.

For several decades, astronomers have used computer models to predict how dwarf galaxies should orbit large galaxies, and every time they found that dwarfs should be scattered randomly over the sky. Powered by supercomputers, these efforts have resulted in simulations of ever-increasing fidelity. None of these computer-created universes have generated dwarfs arranged in a revolving plane like that observed in Andromeda.

“It is very exciting for my work to reveal such a strange structure,” said Anthony Conn of Macquarie University, whose research proved key to this study. “It has left us scratching our heads as to what it means.”

There have been similar claims for an extensive plane of dwarf galaxies about our Milky Way Galaxy, with some claiming that the existence of such strange structures points to a failing in our understanding of the fundamental nature of the universe.

“We don’t yet know where this is pointing us” said Rodrigo Ibata of the Strasbourg Astronomical Observatory. “It flies in the face of our ideas about galaxy formation, but it surely is very exciting.”