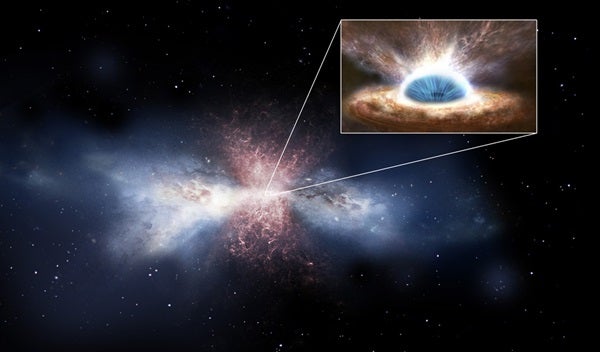

“This is the first study directly connecting a galaxy’s actively ‘feeding’ black hole to features found at much larger physical scales,” said Francesco Tombesi from NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland, and the University of Maryland, College Park (UMCP). “We detect the wind arising from the luminous disk of gas very close to the black hole, and we show that it’s responsible for blowing star-forming gas out of the galaxy’s central regions.”

Star formation takes place in cold, dense molecular clouds. By heating and dispersing gas that could one day make stars, the black hole wind forever alters a large portion of its galaxy.

Tombesi and his team report the connection in a galaxy known as IRAS F11119+3257 (F11119). The galaxy is so distant, its light has been traveling to us for 2.3 billion years, or about half the present age of our solar system.

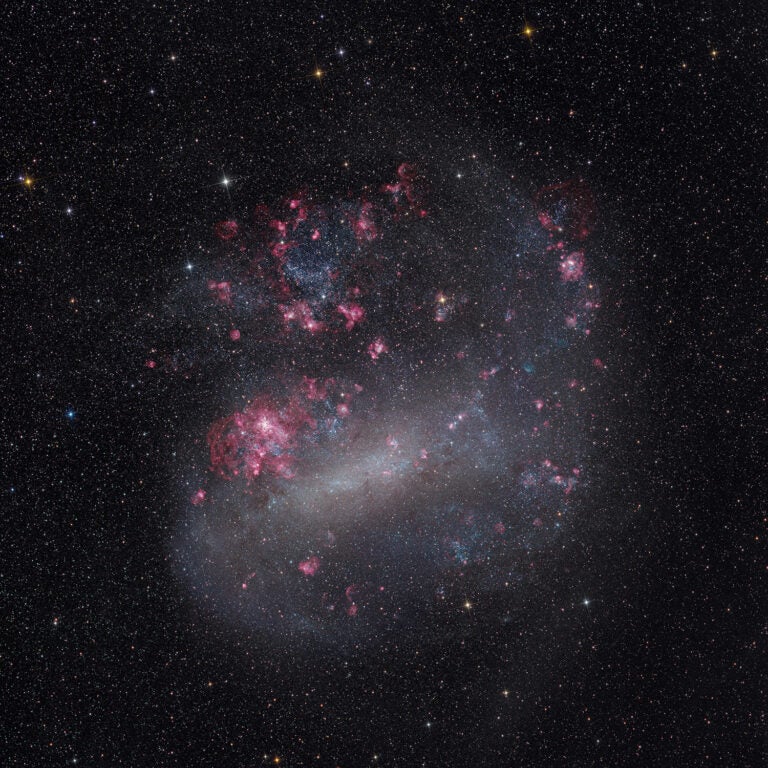

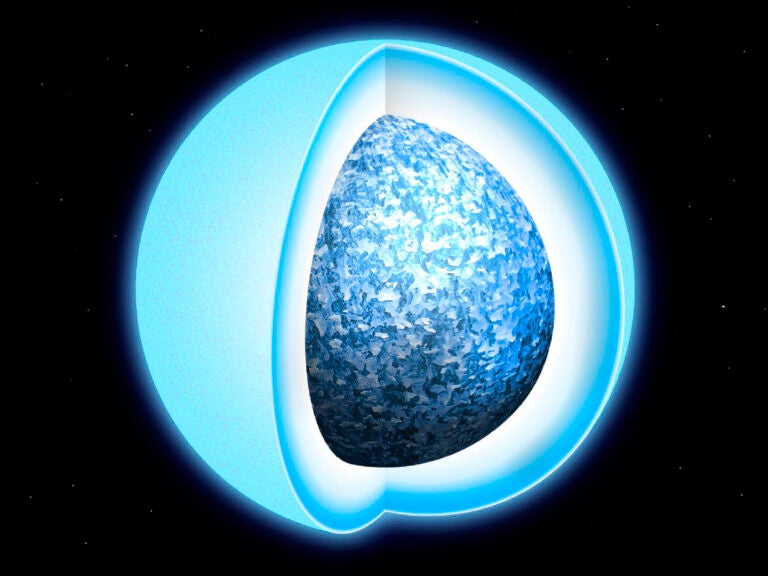

Like most galaxies, including our Milky Way, F11119 hosts a supersized black hole, one estimated at 16 million times the Sun’s mass. The black hole’s activity is fueled by a rotating collection of gas called an accretion disk, which is some hundreds of times the size of our planetary system. Closest to the black hole, the orbiting matter reaches temperatures of millions of degrees and is largely responsible for the galaxy’s enormous energy output, which exceeds the Sun’s by more than a trillion times. The galaxy is heavily enshrouded by dust, so most of this emission reaches us in the form of infrared light.

The new findings resolve a long-standing puzzle. Galaxies show a correlation between the mass of their central black holes and stellar properties across a much larger region called the galactic bulge. Galaxies with more massive black holes usually possess bulges with proportionately greater stellar mass and faster-moving stars.

Black holes grow the same way their host galaxies do by colliding and merging with their neighbors. But mergers disrupt galaxies, which leads to greatly enhanced star formation and sends a flood of gas toward the merged black hole. The process should scramble any simple relationship between the black hole’s growth and the galaxy’s evolution, yet it doesn’t.

“These connections suggested the black hole was providing some form of feedback that modulated star formation in the wider galaxy, but it was difficult to see how,” said team member Sylvain Veilleux from the UMCP. “With the discovery of powerful molecular outflows of cold gas in galaxies with active black holes, we began to uncover the connection.”

In 2013, Veilleux led a search for these outflows in a sample of active galaxies using the Herschel Space Observatory. In F11119, the researchers identified a strong outflow of hydroxyl molecules moving at about 2 million mph (3 million km/h). Other studies using different trace molecules found similar flows.

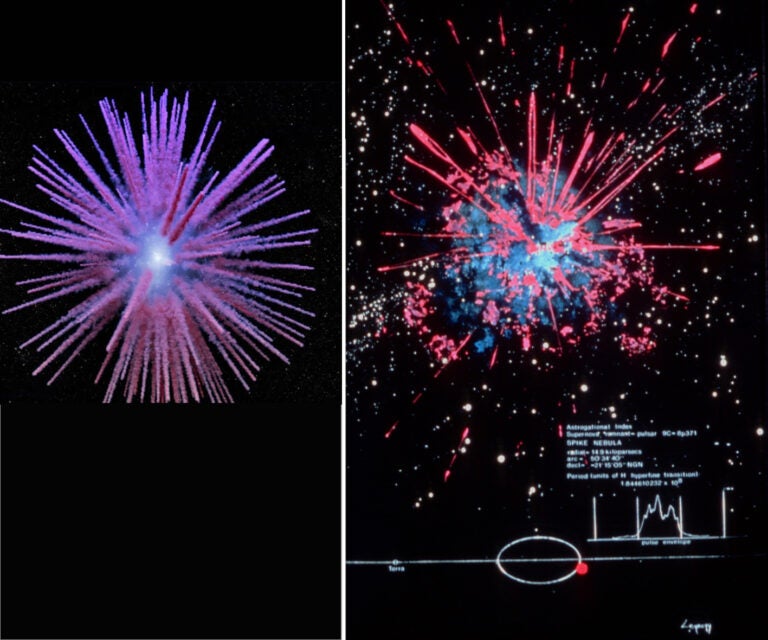

In the present study, Tombesi, Veilleux and their colleagues estimate that this outflow operates up to 1,000 light-years from the galaxy’s center and calculate that it removes enough gas to make 800 copies of our Sun.

In May 2013, the team observed F11119 using Suzaku’s X-ray Imaging Spectrometer, obtaining an effective exposure of nearly three days. The galaxy’s spectrum indicates that X-ray-absorbing gas is racing outward from the innermost accretion disk at 170 million mph (270 million km/h), or about a quarter the speed of light. The region is possibly half a billion miles (800 million km) from the brink of the black hole and about as close to the point where not even light can escape as Jupiter is from the Sun.

“The black hole is ingesting gas as fast as it can and is tremendously heating the accretion disk, allowing it to produce about 80 percent of the energy this galaxy emits,” said Marcio Meléndez from UMCP. “But the disk is so luminous, some of the gas accelerates away from it, creating the X-ray wind we observe.”

Taken together, the disk wind and the molecular outflow complete the picture of black hole feedback. The black hole wind sets cold gas and dust into motion, giving rise to the molecular outflow. It also heats dust enshrouding the galaxy, leading to the formation of an outward-moving shock wave that sweeps away additional gas and dust.

When the black hole shines at its brightest, the researchers say, it’s also effectively pushing away the dinner plate, clearing gas and dust from the galaxy’s central regions and shutting down star formation there. Once the dust has been cleared out, shorter-wavelength light from the disk can escape more easily.

Scientists think ultraluminous infrared galaxies like F11119 represent an early phase in the evolution of quasars, a type of black-hole-powered galaxy with extreme luminosity across a broad wavelength range. According to this picture, the black hole will eventually consume its surrounding gas and gradually end its spectacular activity. As it does so, it will evolve from a quasar to a gas-poor galaxy with a relatively low level of star formation.

The researchers hope to detect and study this process in other galaxies and look forward to the improved sensitivity of Suzaku’s successor, ASTRO-H. Expected to launch in 2016, ASTRO-H is being developed at the Institute of Space and Astronautical Science of the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency in collaboration with NASA Goddard and Japanese institutions.