The Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency (JAXA) sponsors Suzaku with contributions from NASA and participation by the international scientific community.

Galaxy clusters are millions of light-years across, and most of their normal matter comes in the form of hot X-ray-emitting gas that fills the space between the galaxies.

“Understanding the content of normal matter in galaxy clusters is a key element for using these objects to study the evolution of the universe,” said Adam Mantz from NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland.

Clusters provide independent checks on cosmological values established by other means, such as galaxy surveys, exploding stars, and the cosmic microwave background, which is the remnant glow of the Big Bang. The cluster data and the other values didn’t agree.

NASA’s Wilkinson Microwave Anisotropy Probe (WMAP) explored the cosmic microwave background and established that baryons — what physicists call normal matter — make up only about 4.6 percent of the universe. Yet previous studies showed that galaxy clusters seemed to hold even fewer baryons than this amount.

Suzaku images of faint gas at the fringes of a nearby galaxy cluster have allowed astronomers to resolve this discrepancy for the first time.

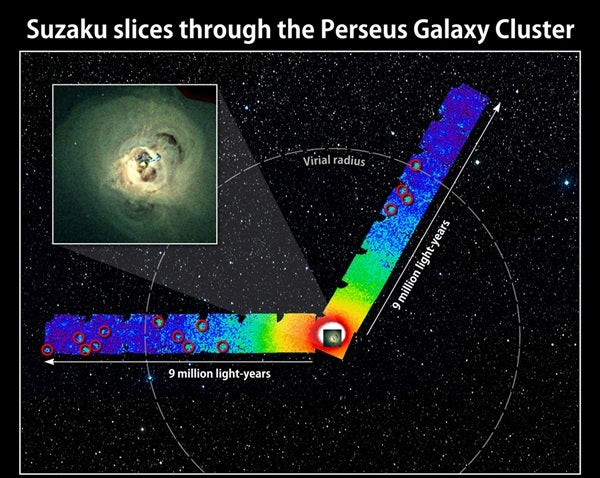

The satellite’s ideal target for this study was the Perseus Galaxy Cluster, which is located about 250 million light-years away and named for the constellation in which it resides. It is the brightest extended X-ray source beyond our own galaxy, and also the brightest and closest cluster in which Suzaku has attempted to map outlying gas.

In late 2009, Suzaku’s X-ray telescopes repeatedly observed the cluster by progressively imaging areas farther east and northwest of the center. Each set of images probed sky regions 2° across — equivalent to 4 times the apparent width of the Full Moon, or about 9 million light-years at the cluster’s distance. Staring at the cluster for about 3 days, the satellite mapped X-rays with energies hundreds of times greater than that of visible light.

From the data, researchers measured the density and temperature of the faint X-ray gas, which let them infer many other important quantities. One is the so-called virial radius, which essentially marks the edge of the cluster. Based on this measurement, the cluster is 11.6 million light-years across and contains more than 660 trillion times the mass of the Sun. That’s nearly a thousand times the mass of our Milky Way Galaxy.

The researchers also determined the ratio of the cluster’s gas mass to its total mass, including dark matter — the mysterious substance that makes up about 23 percent of the universe, according to WMAP. By virtue of their enormous size, galaxy clusters should contain a representative sample of cosmic matter, with normal-to-dark-matter ratios similar to WMAP’s. Yet the outer parts of the Perseus cluster seemed to contain too many baryons, the opposite of earlier studies, but still in conflict with WMAP.

To solve the problem, researchers had to understand the distribution of hot gas in the cluster. In the central regions, the gas is repeatedly whipped up and smoothed out by passing galaxies. But computer simulations show that fresh infalling gas at the cluster edge tends to form irregular clumps.

Not accounting for the clumping overestimates the density of the gas. This is what led to the apparent disagreement with the fraction of normal matter found in the cosmic microwave background.

“The distribution of these clumps and the fact that they are not immediately destroyed as they enter the cluster are important clues in understanding the physical processes that take place in these previously unexplored regions,” said Steve Allen at KIPAC.