More than two dozen astronomers have aligned their research goals to use Chandra to image a set of dying stars in the neighborhood of the Sun. The resulting X-ray images of these dying stars — called planetary nebulae — are shedding light on the violent “end game” of a Sun-like star’s life.

The research team led by Joel Kastner from the Rochester Institute of Technology in New York won seven days of observing time with Chandra in 2011–12 to survey and image nearly two dozen relatively nearby planetary nebulae, resulting in the most comprehensive X-ray survey to date for such objects.

The same team recently won an eight-day time award with Chandra to continue its observing program, and they will begin collecting new X-ray data later this year.

Both the previous and upcoming series of observations are part of the Chandra X-ray Survey of Planetary Nebulae (ChanPlaNS). Leaders in planetary nebula astronomy from seven countries joined forces to win the large Chandra observing time awards.

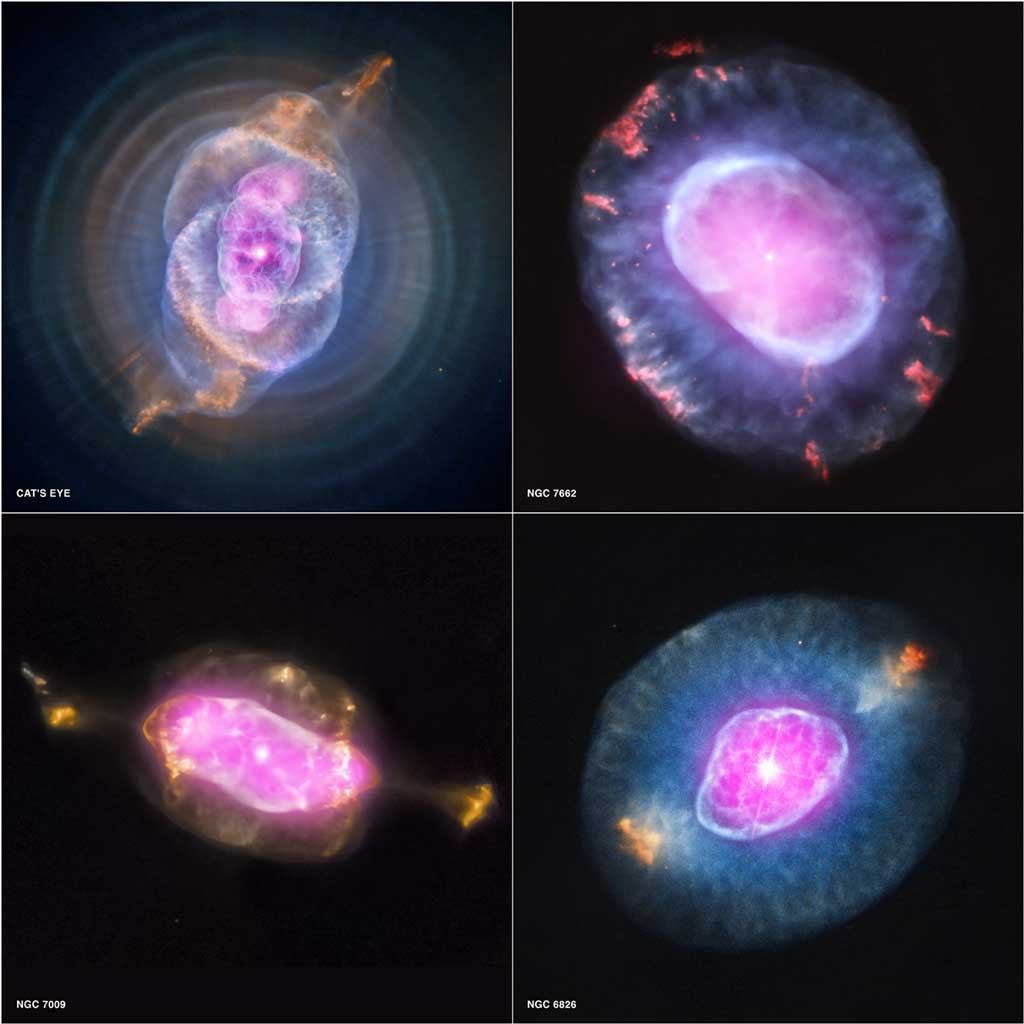

A planetary nebula is a dying star — recently a red giant — that has cast off its outer layers. The newly exposed hot core of the star, which will eventually become a white dwarf, illuminates these ejected layers, while the core’s fast winds sculpt the material into a variety of shapes. The resulting dazzling objects, bearing names like Cat’s Eye, Lemon Slice, and Blue Snowball, are favorite targets of optical and near-infrared telescopes.

“Planetary nebulae have provided astrophysicists with dying star laboratories for more than a century,” Kastner said. “They provide test beds for theories of stellar evolution and give us insight into the origin of heavy elements in the universe and on Earth. Yet we still don’t fully understand why they take on such a dazzling variety of shapes.”

The widespread debate among astrophysicists concerning the planetary-nebula-shaping process led Kastner and Rodolfo Montez Jr., also from the Rochester Institute of Technology, to organize their colleagues to request a large allocation of X-ray satellite observing time to investigate the processes of stellar death and wind collisions in X-rays.

“An X-ray survey of this kind is completely uncharted territory in the planetary nebula world,” Kastner said. “Astronomers working in this area agreed that we need large quantities of time to look at as many planetary nebulae as possible, specifically with Chandra.”

His team is using X-ray imaging to look “under the hood” of planetary nebulae. X-rays cut through the illuminated gas and dust, allowing astronomers to investigate the last tens of thousands of years of history of the dying star that threw off its outer sheaths.

“With Chandra’s exceptional X-ray vision, we can detect the million-degree plasma inside the discarded shells and probe the energies of the stellar winds that shape them,” Kastner said.

In the initial phase of the project, the team collected data for 35 planetary nebulae — 21 previously unobserved and 14 pulled from Chandra archival data — all within roughly 5,000 light-years of the Sun. The recent award will bump the study to a total of 59 objects from among the roughly 120 planetary nebulae identified within this distance.

“Because they all just happen to lie relatively nearby, we think this group of objects is fairly representative of planetary nebulae in general,” Kastner said.

The findings will give theorists material to refine models describing mechanisms that shape planetary nebulae, especially the potential influence of a stellar or even a planetary companion to the dying star.

“The ChanPlaNS study provides fresh new insights into the last dying gasps of stars like the Sun,” Kastner said. “We expect it will clarify what planetary nebulae can tell us about binary star astrophysics and stellar wind interactions.”

Early findings from the study include:

• The collision of the fast wind from the exposed core with the ejected atmosphere causes shock waves that produce the diffuse X-ray emission seen in about 30 percent of the full sample. The Chandra survey data shows that most planetary nebulae with diffuse X-ray emission have sharp-rimmed shells that were ejected less than 5,000 years ago; these compact inner shells are surrounded by fainter halos of material ejected tens of thousands of years earlier.

• About half of the planetary nebulae in the Chandra study show pointlike X-ray sources at their central stars. Many of these point sources show high-energy X-rays that may emanate from a previously undetected companion to the central star. This supports theories asserting that double stars are responsible for the nonspherical shapes of many planetary nebulae.

More than two dozen astronomers have aligned their research goals to use Chandra to image a set of dying stars in the neighborhood of the Sun. The resulting X-ray images of these dying stars — called planetary nebulae — are shedding light on the violent “end game” of a Sun-like star’s life.

The research team led by Joel Kastner from the Rochester Institute of Technology in New York won seven days of observing time with Chandra in 2011–12 to survey and image nearly two dozen relatively nearby planetary nebulae, resulting in the most comprehensive X-ray survey to date for such objects.

The same team recently won an eight-day time award with Chandra to continue its observing program, and they will begin collecting new X-ray data later this year.

Both the previous and upcoming series of observations are part of the Chandra X-ray Survey of Planetary Nebulae (ChanPlaNS). Leaders in planetary nebula astronomy from seven countries joined forces to win the large Chandra observing time awards.

A planetary nebula is a dying star — recently a red giant — that has cast off its outer layers. The newly exposed hot core of the star, which will eventually become a white dwarf, illuminates these ejected layers, while the core’s fast winds sculpt the material into a variety of shapes. The resulting dazzling objects, bearing names like Cat’s Eye, Lemon Slice, and Blue Snowball, are favorite targets of optical and near-infrared telescopes.

“Planetary nebulae have provided astrophysicists with dying star laboratories for more than a century,” Kastner said. “They provide test beds for theories of stellar evolution and give us insight into the origin of heavy elements in the universe and on Earth. Yet we still don’t fully understand why they take on such a dazzling variety of shapes.”

The widespread debate among astrophysicists concerning the planetary-nebula-shaping process led Kastner and Rodolfo Montez Jr., also from the Rochester Institute of Technology, to organize their colleagues to request a large allocation of X-ray satellite observing time to investigate the processes of stellar death and wind collisions in X-rays.

“An X-ray survey of this kind is completely uncharted territory in the planetary nebula world,” Kastner said. “Astronomers working in this area agreed that we need large quantities of time to look at as many planetary nebulae as possible, specifically with Chandra.”

His team is using X-ray imaging to look “under the hood” of planetary nebulae. X-rays cut through the illuminated gas and dust, allowing astronomers to investigate the last tens of thousands of years of history of the dying star that threw off its outer sheaths.

“With Chandra’s exceptional X-ray vision, we can detect the million-degree plasma inside the discarded shells and probe the energies of the stellar winds that shape them,” Kastner said.

In the initial phase of the project, the team collected data for 35 planetary nebulae — 21 previously unobserved and 14 pulled from Chandra archival data — all within roughly 5,000 light-years of the Sun. The recent award will bump the study to a total of 59 objects from among the roughly 120 planetary nebulae identified within this distance.

“Because they all just happen to lie relatively nearby, we think this group of objects is fairly representative of planetary nebulae in general,” Kastner said.

The findings will give theorists material to refine models describing mechanisms that shape planetary nebulae, especially the potential influence of a stellar or even a planetary companion to the dying star.

“The ChanPlaNS study provides fresh new insights into the last dying gasps of stars like the Sun,” Kastner said. “We expect it will clarify what planetary nebulae can tell us about binary star astrophysics and stellar wind interactions.”

Early findings from the study include:

• The collision of the fast wind from the exposed core with the ejected atmosphere causes shock waves that produce the diffuse X-ray emission seen in about 30 percent of the full sample. The Chandra survey data shows that most planetary nebulae with diffuse X-ray emission have sharp-rimmed shells that were ejected less than 5,000 years ago; these compact inner shells are surrounded by fainter halos of material ejected tens of thousands of years earlier.

• About half of the planetary nebulae in the Chandra study show pointlike X-ray sources at their central stars. Many of these point sources show high-energy X-rays that may emanate from a previously undetected companion to the central star. This supports theories asserting that double stars are responsible for the nonspherical shapes of many planetary nebulae.