The object’s curious properties make it a good match for a supermassive black hole ejected from its home galaxy after merging with another giant black hole. But astronomers can’t yet rule out an alternative possibility. The source, called SDSS1133, may be the remnant of a massive star that erupted for a record period of time before destroying itself in a supernova explosion.

“With the data we have in hand, we can’t yet distinguish between these two scenarios,” said lead researcher Michael Koss, an astronomer at ETH Zurich, the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology. “One exciting discovery made with NASA’s Swift is that the brightness of SDSS1133 has changed little in optical or ultraviolet light for a decade, which is not something typically seen in a young supernova remnant.”

Koss and his colleagues report that the source has brightened significantly in visible light during the past six months, a trend that, if maintained, would bolster the black hole interpretation. To analyze the object in greater detail, the team is planning ultraviolet observations with the Cosmic Origins Spectrograph aboard the Hubble Space Telescope in October 2015.

Whatever SDSS1133 is, it’s persistent. The team was able to detect it in astronomical surveys dating back more than 60 years.

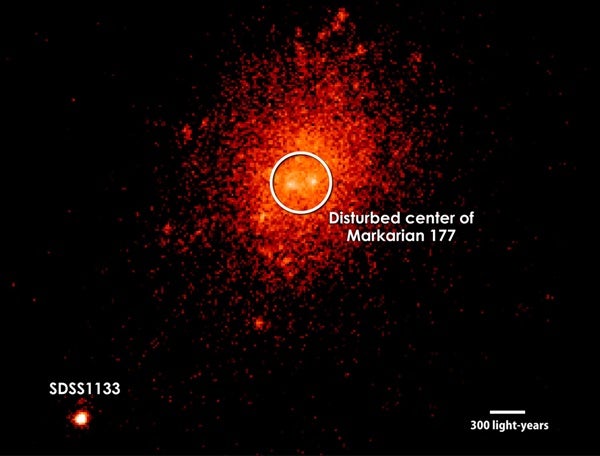

The mystery object is part of the dwarf galaxy Markarian 177, located in the bowl of the Big Dipper, a well-known star pattern within the constellation Ursa Major. Although supermassive black holes usually occupy galactic centers, SDSS1133 is located at least 2,600 light-years from its host galaxy’s core.

In June 2013, the researchers obtained high-resolution near-infrared images of the object using the 10-meter Keck II Telescope at the W. M. Keck Observatory in Hawaii. They reveal the emitting region of SDSS1133 is less than 40 light-years across and that the center of Markarian 177 shows evidence of intense star formation and other features indicating a recent disturbance.

“We suspect we’re seeing the aftermath of a merger of two small galaxies and their central black holes,” said Laura Blecha from the University of Maryland. “Astronomers searching for recoiling black holes have been unable to confirm a detection, so finding even one of these sources would be a major discovery.”

The collision and merger of two galaxies disrupts their shapes and results in new episodes of star formation. If each galaxy possesses a central supermassive black hole, they will form a bound binary pair at the center of the merged galaxy before ultimately coalescing themselves.

Merging black holes release a large amount of energy in the form of gravitational radiation, a consequence of Einstein’s theory of gravity. Waves in the fabric of space-time ripple outward in all directions from accelerating masses. If both black holes have equal masses and spins, their merger emits gravitational waves uniformly in all directions. More likely, the black hole masses and spins will be different, leading to lopsided gravitational wave emission that launches the black hole in the opposite direction.

The kick may be strong enough to hurl the black hole entirely out of its home galaxy, fating it to forever drift through intergalactic space. More typically, a kick will send the object into an elongated orbit. Despite its relocation, the ejected black hole will retain any hot gas trapped around it and continue to shine as it moves along its new path until all of the gas is consumed.

If SDSS1133 isn’t a black hole, then it might have been an unusual type of star known as a luminous blue variable (LBV). These massive stars undergo episodic eruptions that cast large amounts of mass into space long before they explode. Interpreted in this way, SDSS1133 would represent the longest period of LBV eruptions ever observed, followed by a terminal supernova explosion whose light reached Earth in 2001.

The nearest comparison in our galaxy is the massive binary system Eta Carinae, which includes an LBV containing about 90 times the Sun’s mass. Between 1838 and 1845, the system underwent an outburst that ejected at least 10 solar masses and made it the second-brightest star in the sky. It then followed up with a smaller eruption in the 1890s.

In this alternative scenario, SDSS1133 must have been in nearly continual eruption from at least 1950 to 2001, when it reached peak brightness and went supernova. The spatial resolution and sensitivity of telescopes prior to 1950 were insufficient to detect the source. But if this was an LBV eruption, the current record shows it to be the longest and most persistent one ever observed. An interaction between the ejected gas and the explosion’s blast wave could explain the object’s steady brightness in the ultraviolet.

Whether it’s a rogue supermassive black hole or the closing act of a rare star, it seems astronomers have never seen the likes of SDSS1133 before.