Astronomers using the NASA Swift Satellite are tracking a spectacular comet as it closes in on Earth and sheds gas and dust from its vaporized ice. Lulin will pass closest to Earth February 24.

The team, which is led by United Kingdom astronomers, is studying the comet to find out more about its chemistry and to gather clues about the origin of comets and the solar system. Swift is a NASA mission in collaboration with the Science and Technology Facilities Council (STFC) in the UK and the Italian Space Agency (ASI).

“Swift is the ideal spacecraft with which to observe this comet”, said Jenny Carter from the University of Leicester, United Kingdom, and lead investigator of the team studying the Lulin comet. “We won’t be able to send a space probe to Lulin, but Swift is giving us some of the information we would get from just such a mission.”

Dr. Julian Osborne, leader of the Swift project at Leicester said, “The wonderful ease of scheduling Swift and its joint UV and X-ray capability make Swift the observatory of choice for observations like these.”

“The comet is releasing a great amount of gas, which makes it an ideal target for X-ray observations,” said Andrew Read, also at Leicester.

“The comet is quite active,” said team member Dennis Bodewits from the Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland. “The UVOT data show that Lulin was shedding nearly 800 gallons of water each second.” That’s enough to fill an Olympic-size swimming pool in less than 15 minutes.

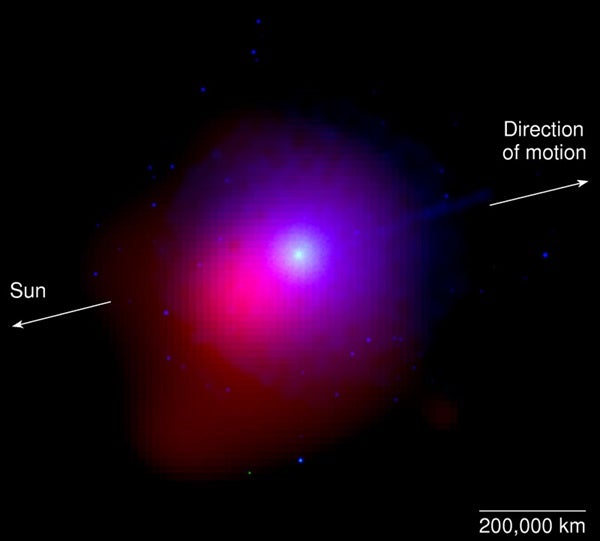

Swift can’t see water directly, but ultraviolet light from the Sun quickly breaks apart water molecules into hydrogen atoms and hydroxyl (OH) molecules. Swift’s UVOT detects the hydroxyl molecules, and its images of Lulin reveal a hydroxyl cloud spanning nearly 250,000 miles (402,000 kilometers), or slightly greater than the distance between Earth and the Moon.

In the Swift images, the comet’s tail extends off to the right. Solar radiation pushes icy grains away from the comet. As the grains gradually evaporate, they create a thin hydroxyl tail. Farther from the comet, even the hydroxyl molecule succumbs to solar ultraviolet radiation. It breaks into oxygen and hydrogen atoms

This interaction, called charge exchange, results in X rays from most comets when they pass within about three times Earth’s distance from the Sun. Because Lulin is so active, its atomic cloud is especially dense. As a result, the X-ray-emitting region extends far Sunward of the comet.

“We are looking forward to future observations of Comet Lulin, when we hope to get better X-ray data to help us determine its makeup,” said Carter. “They will allow us to build up a more complete 3-D picture of the comet during its flight through the solar system.”