The discovery of the unusual behavior in NGC 5548 is the result of an intensive observing campaign using major European Space Agency and NASA observatories, including the NASA/ESA Hubble Space Telescope. In 2013 and 2014, the international team carried out the most extensive monitoring campaign of an active galaxy ever conducted.

There are other galaxies that show gas streams near a black hole, but this is the first time that a stream like this has been seen to move into the line of sight.

The researchers say that this is the first direct evidence for the long-predicted shielding process that is needed to accelerate powerful gas streams, or winds, to high speeds. “This is a milestone in understanding how supermassive black holes interact with their host galaxies,” said Jelle Kaastra of the SRON Netherlands Institute for Space Research. “We were very lucky. You don’t normally see this kind of event with objects like this. It tells us more about the powerful ionized winds that allow supermassive black holes in the nuclei of active galaxies to expel large amounts of matter. In larger quasars than NGC 5548, these winds can regulate the growth of both the black hole and its host galaxy.”

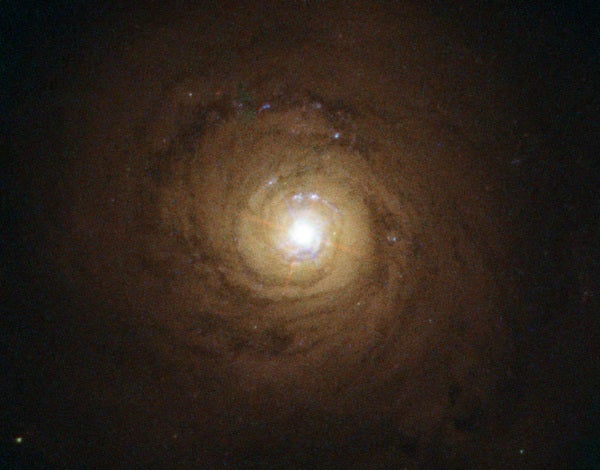

As matter spirals down into a black hole, it forms a flat disk known as an accretion disk. The disk is heated so much that it emits X-rays near the black hole and less energetic ultraviolet radiation farther out. The ultraviolet radiation can create winds strong enough to blow gas away from the black hole, which otherwise would have fallen into it. But the winds only come into existence if their starting point is shielded from X-rays.

Earlier observations had seen the effects of both X-rays and ultraviolet radiation on a region of warm gas far away from the black hole, but these most recent observations have shown the presence of a new gas stream between the disk and the original cloud. The newly discovered gas stream in the archetypal Seyfert galaxy (NGC 5548) — one of the best-studied sources of this type over the past half-century — absorbs most of the X-ray radiation before it reaches the original cloud, shielding it from X-rays and leaving only the ultraviolet radiation. The same stream shields gas closer to the accretion disk. This makes the strong winds possible, and it appears that the shielding has been going on for at least three years.

Directly after Hubble had observed NGC 5548 on June 22, 2013, the team discovered unexpected features in the data. “There were dramatic changes since the last observation with Hubble in 2011. We saw signatures of much colder gas than was present before, indicating that the wind had cooled down, due to a strong decrease in the ionizing X-ray radiation from the nucleus,” said team member Gerard Kriss of the Space Telescope Science Institute in Baltimore.

After combining and analyzing data from the six observatories involved, the team was able to put the pieces of the puzzle together. NGC 5548’s persistent wind, which scientists have known about for two decades, reaches velocities exceeding 2.2 million mph (3.5 million km/h). But a new wind has arisen that is much stronger and faster than the persistent wind.

“The new wind reaches speeds of up to 18 million km/h [11 million mph] but is much closer to the nucleus than the persistent wind,” said Kaastra. “The new gas outflow blocks 90 percent of the low-energy X-rays that come from close to the black hole, and it obscures up to a third of the region that emits the ultraviolet radiation at a distance of a few light-days from the black hole.”

Strong X-ray absorption by ionized gas has been seen in several other sources, and it has been attributed for instance to passing clouds. “However, in our case, thanks to the combined XMM-Newton and Hubble data, we know this is a fast stream of outflowing gas very close to the nucleus,” said Massimo Cappi of INAF-IASF Bologna. “It may even originate from the accretion disk,” added team member Pierre-Olivier Petrucci of CNRS, IPAG Grenoble.