One of the most important and massive parts of the galaxy is the galactic bulge. This huge central cloud of about 10,000 million stars spans thousands of light-years, but its structure and origin were not well understood.

Unfortunately, from our vantage point from within the galactic disk, the view of this central region — at about 27,000 light-years’ distance — is heavily obscured by dense clouds of gas and dust. Astronomers can only obtain a good view of the bulge by observing longer wavelength light, such as infrared radiation, which can penetrate the dust clouds.

Earlier observations from the 2MASS infrared sky survey had already hinted that the bulge had a mysterious X-shaped structure. Now two groups of scientists have used new observations from several of ESO’s telescopes to get a much clearer view of the bulge’s structure.

The first group, from the Max Planck Institute for Extraterrestrial Physics (MPE) in Garching, Germany, used the VVV near-infrared survey from the VISTA telescope at ESO’s Paranal Observatory in Chile. This new public survey can pick up stars 30 times fainter than previous bulge surveys. The team identified a total of 22 million stars belonging to a class of red giants whose well-known properties allow their distances to be calculated.

“The depth of the VISTA star catalog far exceeds previous work, and we can detect the entire population of these stars in all but the most highly obscured regions,” explained Christopher Wegg of MPE, who is lead author of the first study. “From this star distribution, we can then make a three-dimensional map of the galactic bulge. This is the first time that such a map has been made without assuming a model for the bulge’s shape.”

“We find that the inner region of our galaxy has the shape of a peanut in its shell from the side, and of a highly elongated bar from above,” added Ortwin Gerhard, the co-author of the first study and leader of the Dynamics Group at MPE. “It is the first time that we can see this clearly in our own Milky Way, and simulations in our group and by others show that this shape is characteristic of a barred galaxy that started out as a pure disc of stars.”

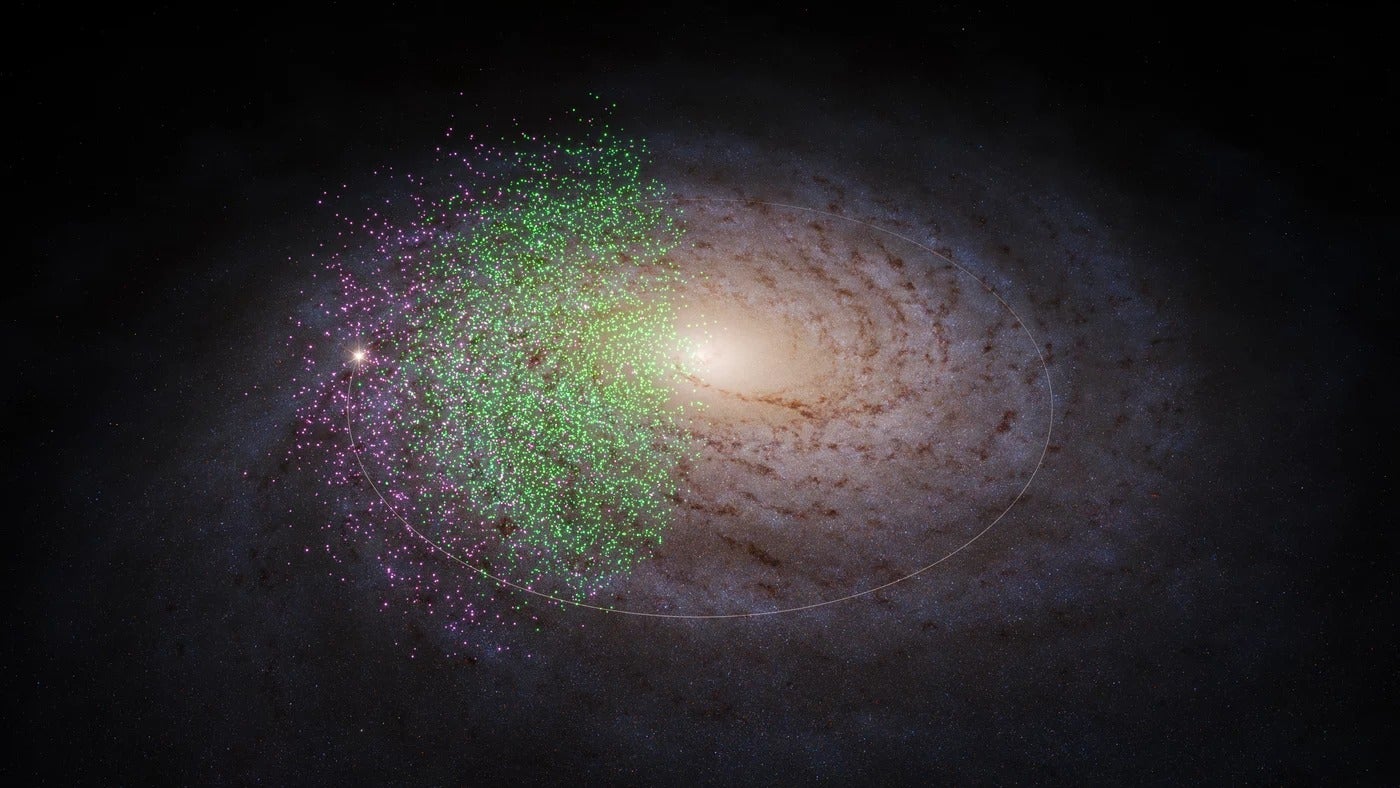

The second international team, led by Chilean Ph.D. student Sergio Vásquez of the Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile in Santiago took a different approach to pin down the structure of the bulge. By comparing images taken eleven years apart with the MPG/ESO 2.2-meter telescope, they could measure the tiny shifts due to the motions of the bulge stars across the sky. These were combined with measurements of the motions of the same stars toward or away from the Earth to map out the motions of more than 400 stars in three dimensions.

“This is the first time that a large number of velocities in three dimensions for individual stars from both sides of the bulge been obtained,” concluded Vásquez. “The stars we have observed seem to be streaming along the arms of the X-shaped bulge as their orbits take them up and down and out of the plane of the Milky Way. It all fits very well with predictions from state-of-the-art models!”

The astronomers think that the Milky Way was originally a pure disk of stars that formed a flat bar billions of years ago. The inner part of this then buckled to form the three-dimensional peanut shape seen in the new observations.