(Editor’s note: This article was first published in 2014 and was titled The 10 most important eclipses in history. Ten years later, the author’s rankings are the same.)

Before I begin, let me make one thing clear: Despite the all-encompassing title, these are my choices for the top 10 most significant eclipses in history. Your list may vary, but I’m pretty sure it would include some of the ones I list below.

All 10 eclipses on this list are solar eclipses, though not necessarily total.

Ready? Here we go, in reverse order, making #1 — in my opinion — the most important eclipse of them all.

#10 — October 22, 2137 B.C. — Don’t drink and observe

Before I came to Astronomy, I spent years in the planetarium field. Every time there was a solar eclipse, I’d haul out the old tale of Hi (or Hsi) and Ho, the two Chinese Royal Astronomers (OK, astrologers) who lost their heads because they got drunk and failed to predict an eclipse. It’s a great, if grisly, tale about being diligent when it comes to science. And it’s probably true. Probably.

#9 — July 19, 418 — Proof that the Sun is bright

During the total phase of this eclipse, the Greek church historian Philostorgius made a sketch of stars and of a comet — the first one ever discovered during an eclipse.

#8 — July 17, 334 — Prominent discovery

The Latin writer and astrologer Julius Firmicus Maternus gave the earliest description of a prominence during this eclipse, which he observed from Sicily. Interestingly, this event was an annular eclipse and not a total one.

#7 — July 28, 1851 — Kodak moment

Russian photographer Berkowski (nobody knows his first name) takes the first successful image of totality during this eclipse. He mounted a 2.4-inch refractor atop one of the instruments at the Royal Observatory in Königsberg, Prussia (now Kalingrad, Russia), and exposed a daguerreotype plate for 84 seconds.

#6 — March 20, 71 — Crowning glory

The Greek philosopher Plutarch is the first to describe the corona, the thin outer atmosphere of the Sun, in his book De Facie in Orbe Lunae (On the face which appears in the Moon). Plutarch, through a character in the book named Lucien, says, “Even if the moon, however, does sometimes cover the sun entirely, the eclipse does not have duration or extension; but a kind of light is visible about the rim which keeps the shadow from being profound and absolute.”

#5 — May 22, 1724 — Corona lite

Although Plutarch described the corona some 17 centuries earlier, it was the Spanish astronomer José Joaquín de Ferrer who gave the phenomenon its name after viewing this total solar eclipse from Kinderhook, New York. Corona is Latin for “crown.” He also correctly surmised that the corona was part of the Sun rather than the Moon because of its size.

#4 — August 18, 1868 — Elementary, my dear astronomer

French astronomer Pierre Jules César Janssen and British astronomer J. Norman Lockyer independently discover an unknown line in the Sun’s spectrum. Lockyer proposed that the new line was due to the presence of a hitherto undiscovered element, which he named helium because in mythology Helios was the name of the Greek Sun god. This element — the second most abundant in the cosmos — would not be found on Earth for another 27 years.

#3 — May 15, 1836 — Baily’s beads

English astronomer Francis Baily provided the first explanation of why we see beads of sunlight just before and just after totality during solar eclipses (and also during some annular eclipses). He explained that it we were viewing the Moon’s irregular surface, especially hills and valleys, which alternately blocked or allowed sunlight to peek through to our eyes.

#2 — Various dates — Your first totality

Many of you reading this might have never seen a total solar eclipse. Rejoice! Your next chance is Monday, April 8, 2024. It will rank as the most spectacular thing you ever will see, and you’ll remember it for the rest of your lives. Those of us who have been fortunate enough to stand under the daytime shadow of the Moon always have the fondest memories about the first one we ever saw. But no matter what your “totality count” is, every one is special.

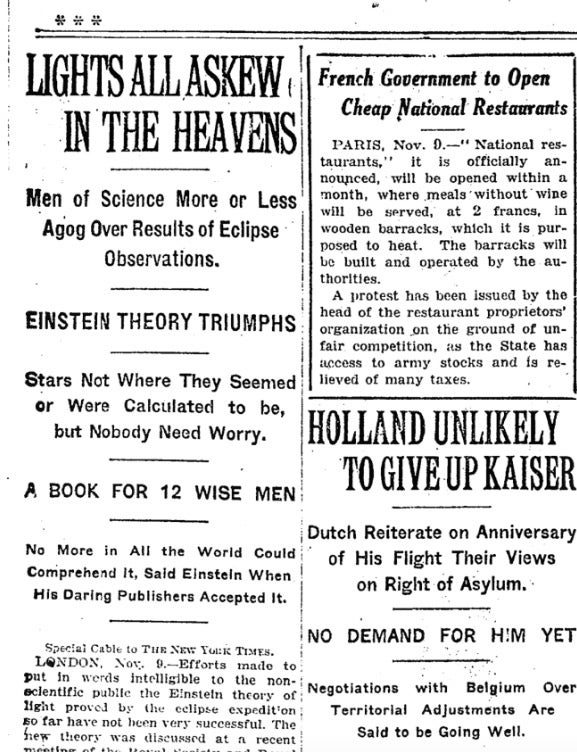

#1 — May 29, 1919 — The eclipse that proved general relativity

There is one eclipse, however, that tops even the first one you or I saw or will see. In 1916, German-born physicist Albert Einstein published the general theory of relativity. In it, Einstein said space could be curved by of the influence of the gravity of any body with mass. To prove this, English astrophysicist Arthur Eddington proposed a test during which observers would photograph the Sun during a solar eclipse’s totality to see if the Sun’s gravity made any stars visible that would not normally be seen. Indeed, during the May 29, 1919 eclipse, two teams of astronomers took pictures that showed conclusively that gravity warps space, and the name Albert Einstein became synonymous with “genius” from that point on.