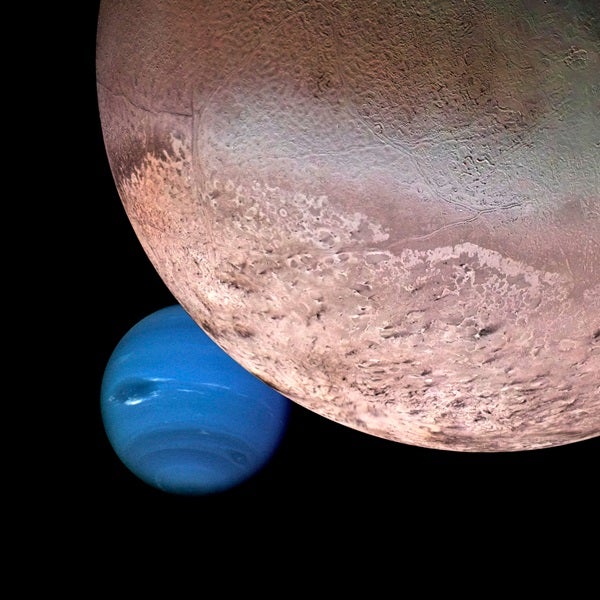

Scientists want to go back to get a better look.

“We’ve only seen part of its surface, and that was back in 1989,” says Louise Prockter, director of the Lunar and Planetary Institute, who’s leading the charge for a Triton mission called Trident. Her team discussed the mission at the Lunar and Planetary Science Conference in Houston earlier this month. “We think that (Triton) has an ocean. It’s in a highly inclined orbit, so it’s probably a captured Kuiper Belt Object.” She says that the activity of being captured and pulled into its current orbit could have warmed it. “All models suggest there’s an ocean beneath its surface … It indicates you could make an ocean world, rather than forming it in place.”

Little Mission with Big Returns

Prockter’s team is proposing the mission under NASA’s Discovery program for low-cost missions. But competition will be steep. Other proposed missions including exploring Venus or returning samples from Mars. And even if Trident is eventually selected, the development timeline means a launch wouldn’t happen until 2026, just in time for an arrival at Triton in 2038.

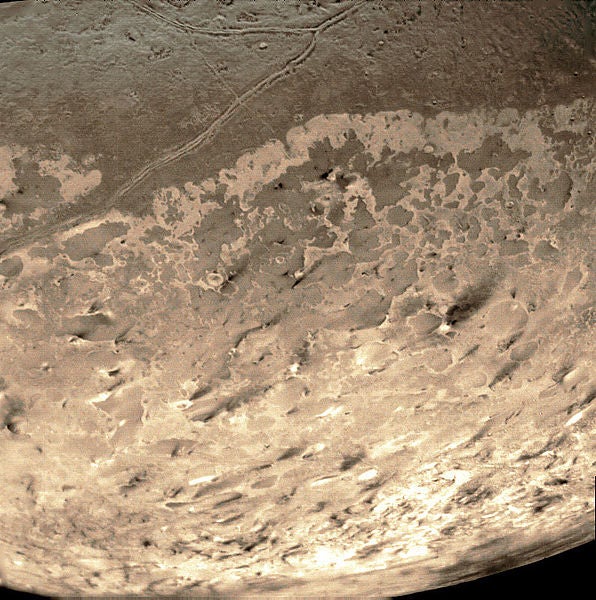

One of the prime mission goals is to understand the plumes Voyager spotted three decades ago. Mars and comets sometimes puff out material when the sun heats their surfaces, causing small explosions of warmed gases and materials. The volcanically active Jovian moon Io also spouts off material. But Triton’s plumes are more likely to imitate the icy moons Europa and Enceladus, and possibly be spouting material from its ocean interior.

Last time, the nitrogen-rich plumes occurred in Neptune’s southern hemisphere during summer, when the sun illuminated that area, possibly heating it and contributing to the activity. “We want to see those areas that Voyager saw, so we have to go before 2040,” Prockter says. After that, the sun will move north, and scientists will lose their best chance at repeating Voyager’s lucky observations. A 2026 launch also allows them a more or less straight shot out, with only a small gravity assist from Jupiter along the way. Since Triton’s seasonal cycle takes 80-plus years, such an opportunity won’t come back again for quite a while.

A Budget Mission

While New Horizons made an even longer journey to Pluto in nine years, it was a more ambitious mission, launched on a larger rocket. In order to meet Discovery-level costs, Trident would launch on a smaller vehicle at a more sedate speed. It would need all 12 years to get to Neptune’s orbit. But it will also be a smaller craft.

In addition to a smaller launch vehicle, part of the mission’s low cost will come from recycling equipment developed for other missions. “There are no miracles. We’re not doing anything fancy,” Prockter says. Instead, they’ll borrow from missions like JUICE (the JUpiter ICy moons Explorer), cobbling together a suite of instruments to essentially create a mission from off-the-rack components, instead of designing them from scratch.

Their design would produce a narrow angle camera that works like a telescope, so NASA could image the moon from a distance on approach and departure. It would also include a wide-angle camera that can see in low light for the flyby itself, to more carefully image the surface. They’ll have a spectrometer to study the composition of the moon and any plumes they spot. And Trident will also sport a magnetometer, an instrument the Galileo spacecraft used to detect underground oceans on Jupiter’s icy moons.

Prockter says their cameras, even with just a flyby, would be able to capture almost the entire surface of Triton. “We can still make out lots of geologic features,” she says. And she also points out that Triton’s surface is very new, second only to Io in the solar system. “It’s probably active today,” Prockter says. “Having an active body so far out in the solar system would be incredible … It’s such a strange and alien world. We want to go and figure it out.”