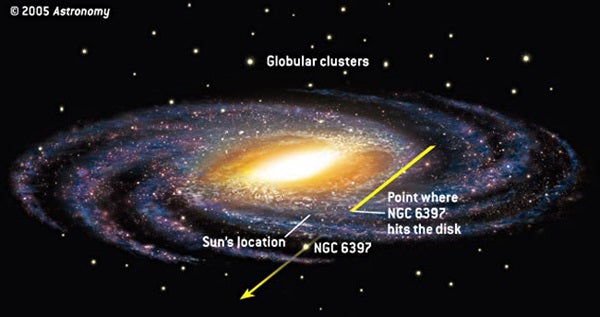

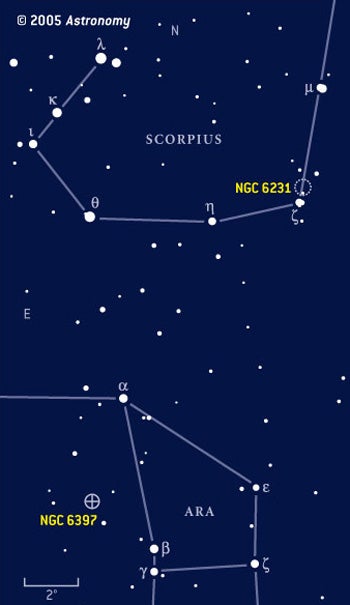

In 2004, Richard Rees of Westfield State College in Westfield, Massachusetts, and Kyle Cudworth of the University of Chicago’s Yerkes Observatory in Williams Bay, Wisconsin, announced they’d found just such an occurrence in our own Milky Way. The culprit is NGC 6397, a 12-billion-year-old globular cluster about 7,200 light-years away in the constellation Ara. The globular has a mass of about 250,000 Suns.

Rees, Cudworth, and colleagues studied photographs of NGC 6397 taken between 1893 and 1990 to determine how the cluster moved across the sky. Together with spectroscopic measurements, which revealed the cluster’s line-of-sight motion via the Doppler effect, the astronomers calculated where the cluster is headed — and where it had been. NGC 6397 plunged through the Milky Way’s disk about 4.5 million years ago. It now lies about 1,500 light-years beneath the galaxy’s disk and is moving into the halo.

Rees and Cudworth calculated where NGC 6397 hit the disk and tracked the impact point through 4.5 million years of our galaxy’s rotation. “When I looked at a map of that region of the sky, NGC 6231 jumped out at me,” explains Rees. NGC 6231 is an open star cluster less than 5 million years old and located between 5,200 and 6,500 light-years away in Scorpius. “I’m surprised we found something that easily,” he muses. The astronomers first presented their results at the January 2004 meeting of the American Astronomical Society in Atlanta, Georgia.

Using published motions of NGC 6231, Rees and Cudworth calculated its three-dimensional space velocity and extrapolated backward to see where the open cluster was when NGC 6397 struck the disk. “The biggest uncertainty is that we don’t know the distance to NGC 6231 very well,” says Rees. Its position at the time NGC 6397 hit the disk matches better if NGC 6231 is now at the far end of current distance estimates. “But even if it’s at the near end, they match tolerably well.” Rees plans to look for additional cases of star formation triggered by passing globular clusters.

Hearing about this study made John Wallin’s day. “It’s really nice when a crazy theory turns out to be true,” he says.