New research, published today in Nature Astronomy, found that water may have formed in the first 200 million years of the universe’s lifetime. The life-giving molecule may have been created so quickly by the deaths of the universe’s first stars. The study also found that rocky planets could be built in the water-rich environment left behind, all before the first galaxies even existed.

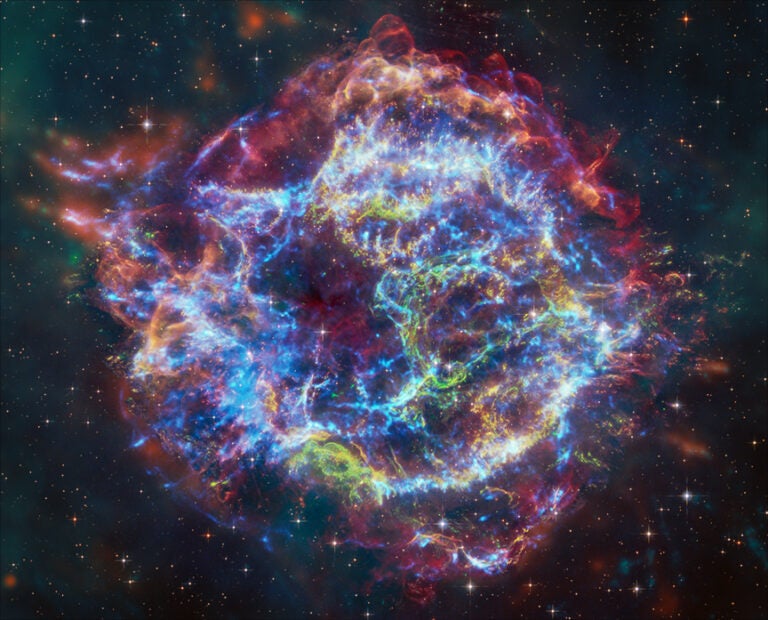

Principal investigator Daniel Whalen of Portsmouth University in the United Kingdom and his colleagues found that a rare type of supernova created only by the earliest stars formed enough water to drench the surrounding regions where the next generations of stars and their planets would be born.

The first stars

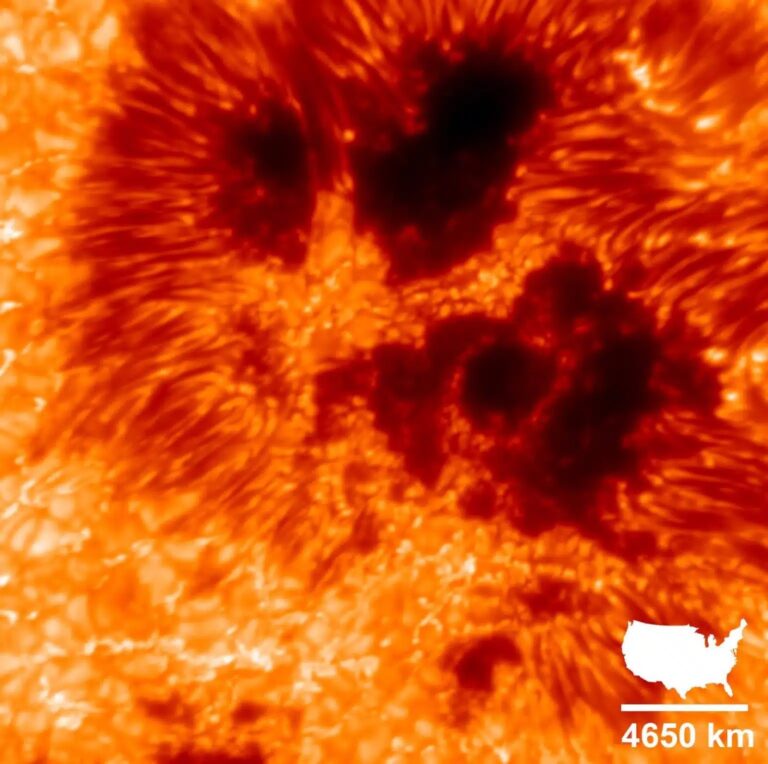

The very first stars formed from the hydrogen and helium that filled the universe after the Big Bang. These suns weren’t in galaxies — those didn’t exist yet — but instead at the intersections where cobweblike filaments of dark matter, strung between empty voids, met. Gravity drew gas to these intersections and when the density was high enough, the first stars were born.

These stars were huge, as much as 300 times as massive as our Sun. Their temperatures were high and they burned through their fuel quickly. And they died in supernovae that spewed new elements into their surroundings.

Whalen and his colleagues simulated two types of supernovae thought to be prevalent among the first generation of stars by following the lives of stars with 13 and 200 solar masses. “We watched primordial stars form … and then they blew up,” Whalen says.

The first type of supernova is a core-collapse supernova. These occur in stars at least eight to 10 times more massive the Sun. As stars age, they deplete the hydrogen in their core. They then evolve through consecutive cycles of fusion burning in an onionlike structure around the core, fusing ever-heavier elements into new ones in a series of thin layers.

Iron is the last element created, because iron cannot be fused to create energy. Then, in the ongoing struggle between gravity and nuclear fusion (which creates photons that hold the star up), gravity finally wins and the core collapses, creating a neutron star, which cannot be further compressed. The rest of the star comes crashing down; it hits the core and rebounds, creating a shock wave. Within the shock wave, even more fusion occurs, this time creating elements heavier than iron.

At the same time, the intense pressures in the core create neutrinos, which further energize the rebounding material, ultimately tearing the star apart. And all that material — including newly formed metals (astronomers refer to any elements other than hydrogen and helium as metals) — is hurled outward, leaving behind only the dense stellar core.

Alternatively, pair-instability supernovae occur only in stars well over 100 times the mass of the Sun. The cores of these stars can reach temperatures so hot that their photons turn into particles — pairs of electrons and positrons. The conversion of energy into matter abruptly reduces the pressure in the core so that it suddenly contracts. This releases enough energy to quickly kick off more thermonuclear burning that results in a shock wave that tears the star apart.

The effect is like that of a huge hydrogen bomb, Whalen says. The explosion is so powerful that it completely tears the star apart, leaving no core behind. Every trace of stellar material is hurled outward into space.

A pair-instability supernova can unleash as much as 100 times the energy of a core-collapse explosion. “They were the first super, super powerful factories of heavy elements in the universe,” Whalen says.

After the explosion

What happened after the supernovae amazed Whalen and his colleagues.

When the first stars exploded, they were surrounded by leftover hydrogen gas from the star. Whalen’s simulations showed that the leftover material included small clumps bound together by gravity. As hot ejecta from the supernova raced outward, the metals within it — including oxygen — mixed with the hydrogen, accelerating their gravitational collapse. The added metals also helped the clumps to cool, allowing the oxygen to combine with hydrogen to form water.

Things happened a little differently in the two cases, though. While material from a core-collapse supernova flowed relatively smoothly outward, the material hurled by a pair-instability supernova was chaotic, thanks to the more powerful explosion. The increased turbulence in the second case created more clumps — and because the ejecta didn’t have to travel as far, it also formed water significantly quicker. Additionally, the higher pressures and temperatures of the pair-instability supernova created material with more metals than the core-collapse event, allowing the clumps to cool even faster.

The result is a significant temporal difference. While core-collapse supernovae form water within 30 million to 90 million years after their explosion, pair-instability supernovae can hydrate their surroundings in only 3 million years.

The amount of metals also made a huge difference. A core-collapse supernova creates only a few tenths of a solar mass worth of metals, Whalen says. Pair-instability supernovae, on the other hand, makes closer to 100 solar masses of metals, including 30 to 50 solar masses of oxygen. That can produce a lot more water.

The clumps around a core-collapse supernova became 10 to 30 times as water-rich as diffuse clouds of gas in the Milky Way today. Pair-instability supernovae created even richer clumps, only a few times less water-rich than the solar system today.

Because they are more massive, the stars that generate pair-instability supernovae also got a head start on their cousins. These suns are born, burn, and die in about 2.5 million years. The stars that produce core-collapse supernovae take closer to 12 million years to evolve. So, water was seeded into the region around the most massive stars first.

The first planets?

In both cases, the clumps left behind are expected to form the next generation of stars. But what about planets? There has been doubt that planets could form from the debris created by the first stars. But some simulations do suggest that these clumps could indeed be the site of future planet formation.

Guideo De Marchi, an astronomer at the European Space Research and Technology Center who was not involved in the new study, has identified protoplanetary disks in environments similar to those in the early universe — specifically those with low metallicity (i.e., few heavy elements). In 2003, he says, Hubble found evidence a massive planet in a globular cluster with very low metallicity.

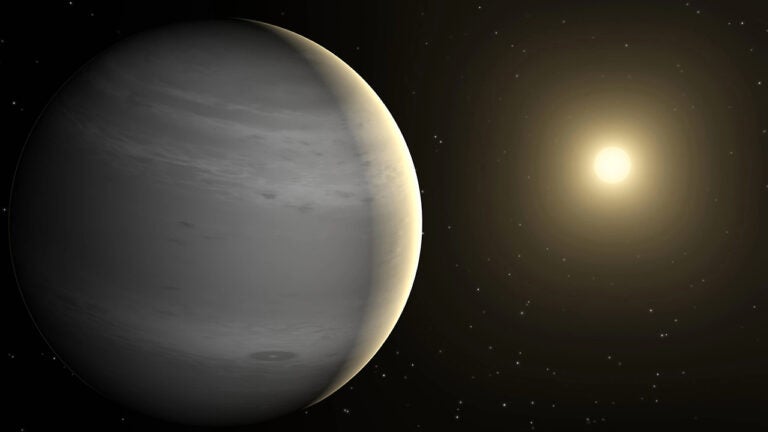

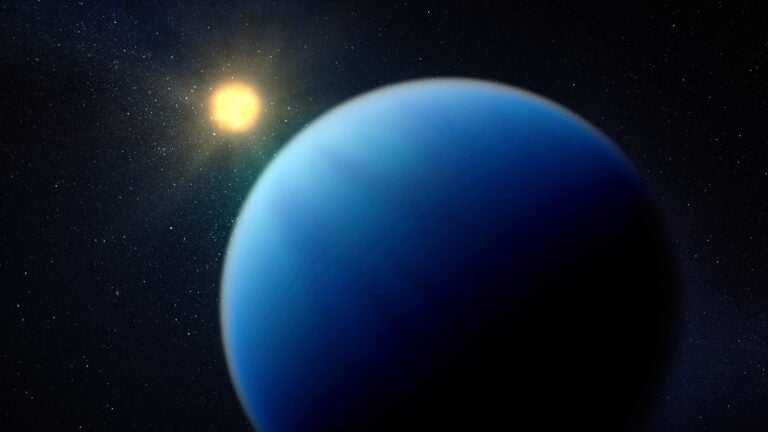

The type of supernova might also affect the type of planets that form. Gas giants are made up predominantly of hydrogen and helium in their outer layers, while rocky worlds need more silicates and other heavy elements to form. Because material created by a pair-instability supernova has higher metallicity (more complex elements) than that from a core-collapse supernova, stars born from a core-collapse supernova have sufficient material to create Jupiter-like planets, while the descendants of a pair-instability explosion could be surrounded by rocky worlds.

And all of this may have happened before the first galaxies ever formed.

Can we see it?

There is a caveat: Whalen and his colleagues only explored individual explosions. Most likely, several first-generation stars would form together where cosmic filaments intersect. Each star would bathe the entire region in radiation, which has the potential to shatter the newly formed water molecules. At the same time, each region would also contain dust, which would shield the water from that radiation.

“It is a delicate balance,” of those two forces, says De Marchi. But he remains optimistic. “The fact that we see the presence of water in protoplanetary disks in low metallicity environments [like] the Small Magellanic Cloud means that some of it can be preserved,” he says.

Hunting for observable signs of water in the early universe remains a challenge. So, too, does spotting the first generation of planets around single stars. Even clumps of stars would shine too dimly to be spotted with today’s instruments. So, Whalen and his colleagues are working to understand what sort of signal those first water-rich stars and planets might produce as a whole.

“An entire population [of water-rich stars and planets] in the early universe might create this hazy water … emission background,” Whalen says. That emission could potentially be detected in the coming decade by either the Atacama Large Millimeter Array in Chile or the Square Kilometer Array under construction in Australia and South Africa.