Pitting young against old, conservative against radical, this cosmological showdown focused on two wildly different theories about the architecture of the universe. Though the conclusion was somewhat unfulfilling at the time, ultimately, the insights gained from the spirited debate helped fundamentally reshape how we view our place in the cosmos.

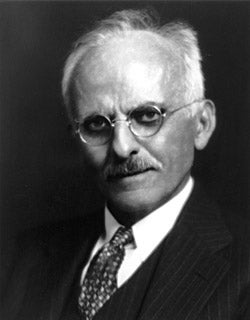

Neither the 30-something Shapley nor the balding, bespectacled Curtis came to fisticuffs on April 26, 1920. And their contest in the Guastavino-tiled opulence of the Smithsonian Institution’s Baird Auditorium was an unlikely fighting ring. But a clash of the scientific titans it most definitely was.

“There’s no question that Curtis was a gifted speaker,” John Mulchaey, director of the Carnegie Observatories at the Carnegie Institution for Science, tells Astronomy. “Shapley was much more uncomfortable in front of crowds, and that no doubt affected his performance.”

But Curtis also seized the opportunity for a sprightly debate with relish. “A good friendly scrap is an excellent thing, once in a while,” he quipped amiably in a letter to Shapley. “Sort of clears up the atmosphere.”

The topic of the Great Debate

Although little remembered, their Great Debate a century ago hinged on a lingering uncertainty about the extent of our Milky Way and whether it constituted the entire universe or was just one of many “island universes” that we now call galaxies. Former journalist Shapley, who joked that he decided to study astronomy only because he could pronounce it, proved the Milky Way was at least 10 times bigger than previously thought.

Furthermore, he showed our solar system resides not in the Milky Way’s heart, but far from its center.

Shapley believed that “spiral nebulae” like Andromeda (now known to be our closest galactic neighbor) were part of the Milky Way. To regard them as anything more was to admit the cosmos was larger than most astronomers in the early 20th century were willing to accept.

“He was really convinced the universe had to be the Milky Way,” explains Mulchaey, “because his estimate of the Milky Way suggested it was very big. Much too big for there to be much else besides it.”

Setting the stage for a cosmological showdown

Ideas to thrash out the issue were sown in 1919, when George Hale, head of Mount Wilson Observatory, proposed a debate at the National Academy of Sciences to consider the merits of either relativity or island universes. But academy secretary Charles Abbot was initially skeptical, fearing that the debate would fall flat because relativity had already been “done to death” by academics and audiences wouldn’t care about island universes.

Shapley also wanted to reframe the debate as a more gentlemanly discussion. Curtis countered with “we could be just as good friends if we did go at each other, hammer and tongs!”

Eventually, it was agreed that each speaker would get 40 minutes — hardly enough time to get warmed up, Curtis grumbled. And at 8:15 p.m. sharp on the last Monday of April 1920, the two men faced an audience of academics, members of the public, and, so the story goes, Albert Einstein.

“The two authors really talked around each other and were in some sense not even talking about the same thing,” says Mulchaey. “I suspect that Shapley’s concentration on the Milky Way also did not help his case, since everyone else was there to debate the island universes. This, combined with his underwhelming speaking abilities, probably led to Curtis being declared the winner, irrespective of the actual evidence.”

The results did no great harm to either scientist’s career, though; Shapley won the directorship of Harvard College Observatory, while Curtis took the helm of Allegheny Observatory.

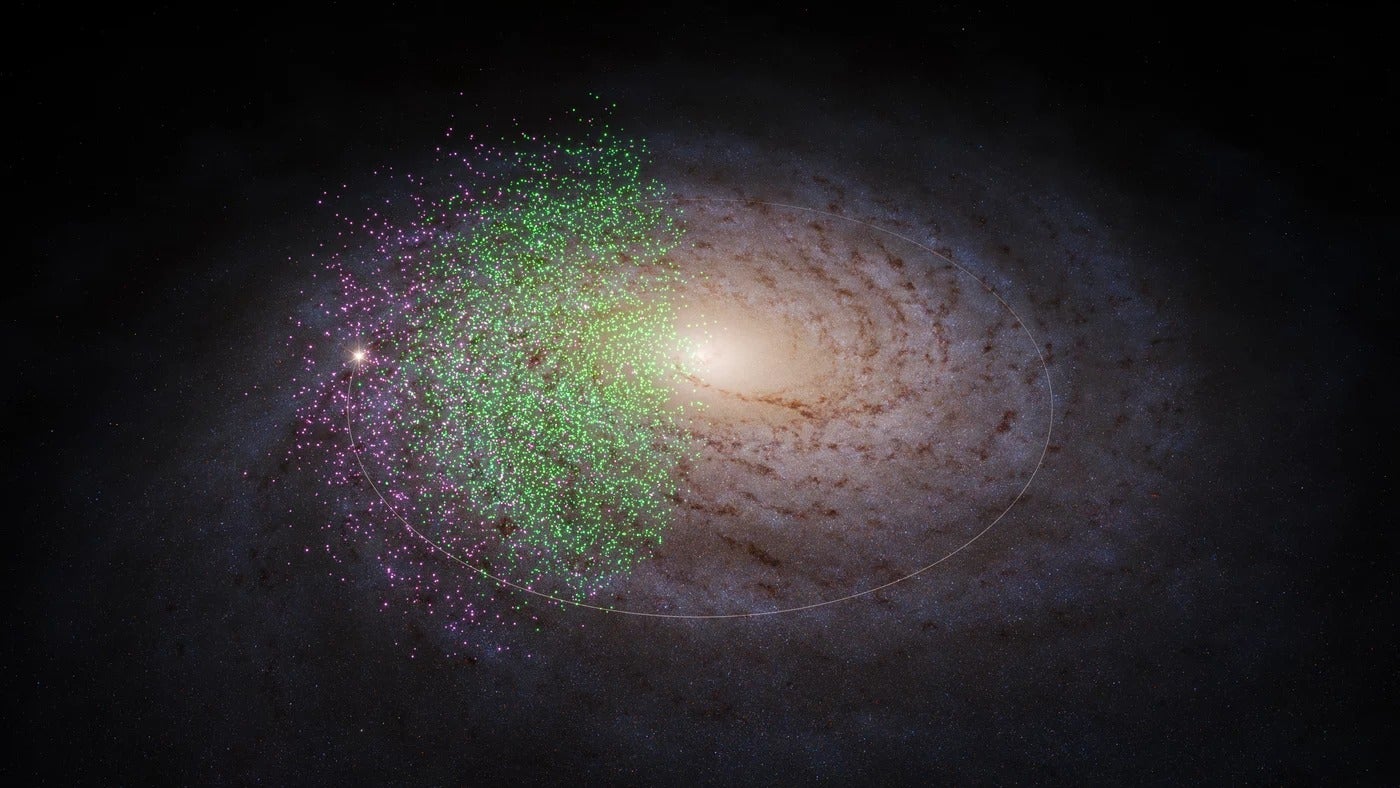

Later that decade, Edwin Hubble’s measurements of Cepheid variable stars proved that Andromeda did indeed lie outside the Milky Way, forever changing our understanding of the scale of the universe.

“The distance measurement to Andromeda was the most significant game changer since the work of Copernicus/Galileo,” asserts Mulchaey. “Hubble effectively discovered the universe. It’s hard to do much better.”

A century after the Great Debate

Nowadays, there are far fewer opinion-polarizing debates in astronomy. “I suspect this is more a reflection on how modern astronomical research works,” explains Mulchaey. “Back in 1920, most individuals worked alone and communication about new results or observations was fairly slow.

“These days, we all work in collaborations where ideas can be easily shared,” he says. “We can hear about new observations or results almost as they happen, as opposed to having to wait until a new scientific paper is completed. Because many papers have multiple authors, there is also a lot of extensive discussion going on before a paper is even written.”

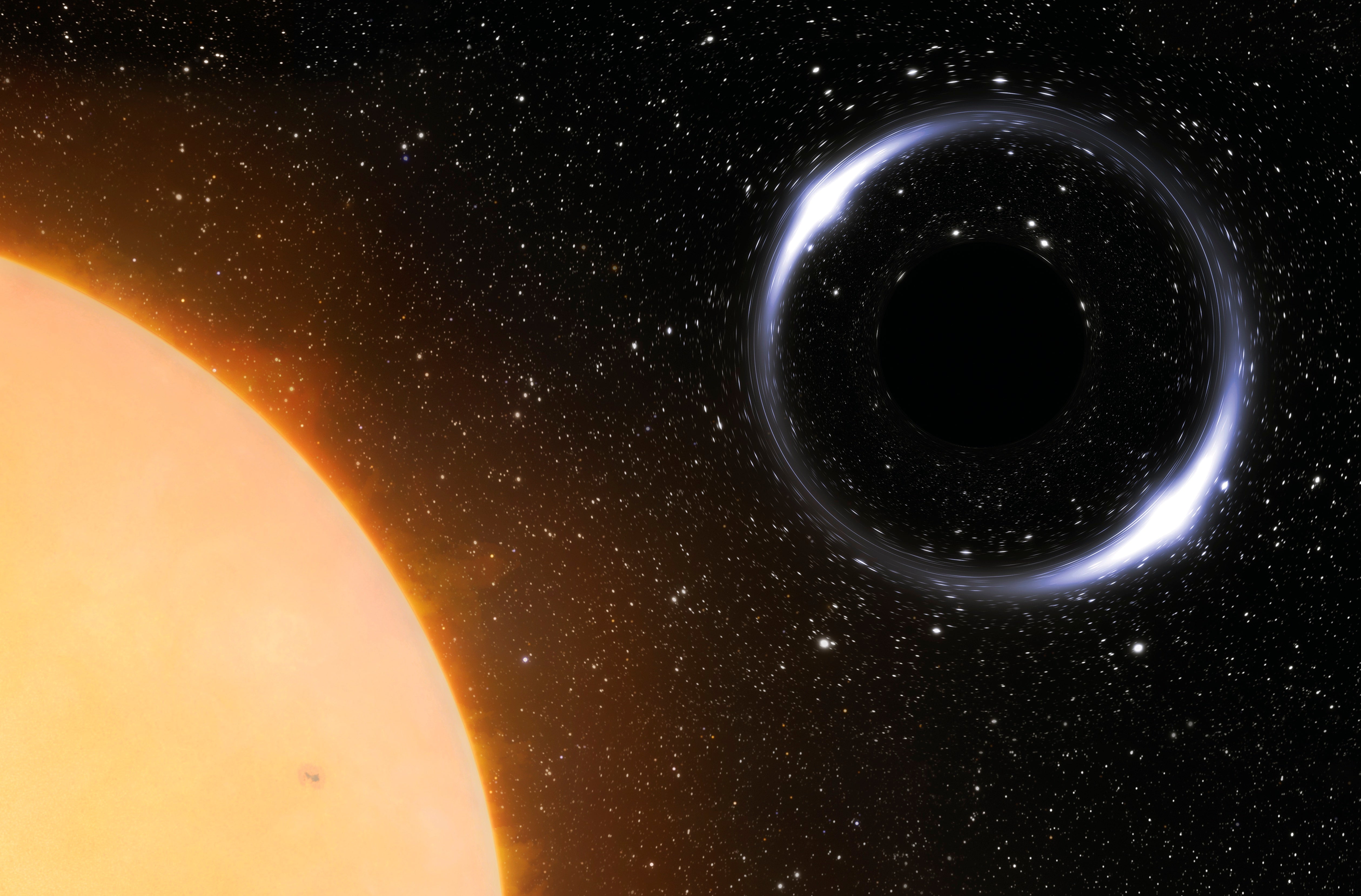

However, Mulchaey identified four modern-day astronomical unknowns with a wide range of possible explanations — dark matter, fast radio bursts, the fate of the universe, and extraterrestrial life. However, he remains unconvinced that they will be solved anytime soon.

“We’ve had the dark matter problem for decades now,” he says. “If you asked me back in 1990, I would have told you we will have an answer by 2020. The fact that we don’t suggests to me that we might be fundamentally missing something.”

And although a dark matter particle could be detected tomorrow and the search for life on Mars and in exoplanetary atmospheres continues, Mulchaey is pessimistic of a near-term breakthrough in these realms.

Fast radio bursts, though? We have a reasonable chance to figure those out in the not-too-distant future.

Get to know some of the key women who have overcome prejudice to make an impact in astronomy in our free downloadable eBook: Women in Astronomy.

The irony of the Shapley-Curtis debate is that it advanced our knowledge of the cosmos, while simultaneously revealing our insignificance on the grandest scales.

“We believe we have a good, basic understanding of how the universe works,” says Mulchaey. “I think that wasn’t the case in 1920. That’s really what the Great Debate was about. There was just not enough information to favor one idea over the other. It really took Hubble’s breakthrough observations of Andromeda to make a leap in our understanding and show that one model was clearly right.”

The author would like to express thanks to Dr. John Mulchaey — director and Crawford H. Greenewalt Chair of the Carnegie Observatories — for his insights in preparing this article.