Each September, almanacs start to appear across America. Most notable is The Old Farmer’s Almanac, which has been in print since 1792. Its cover states that it is “Useful, with a Pleasant Degree of Humor,” and the little book is filled with astronomical information, weather predictions, and more.

The U.S. government is also in the almanac business, and has been for more than 150 years. Its publications include The Nautical Almanac, The Air Almanac, and The Astronomical Almanac.

The website of the Astronomical Applications Department of the U.S. Naval Observatory notes: “Scientific research, timekeeping, calendars, and navigation have all depended upon the practical skills of positional astronomy for thousands of years.” Today, astronomical almanacs provide positions of the Sun, the Moon, and the planets. They guide automated telescopes, set planetariums, and help in navigation.

Early almanacs

For centuries, these almanacs were produced by astronomers through painstaking calculations. The process was difficult — and the resulting publications were often filled with errors from faulty instruments and poor observational skills.

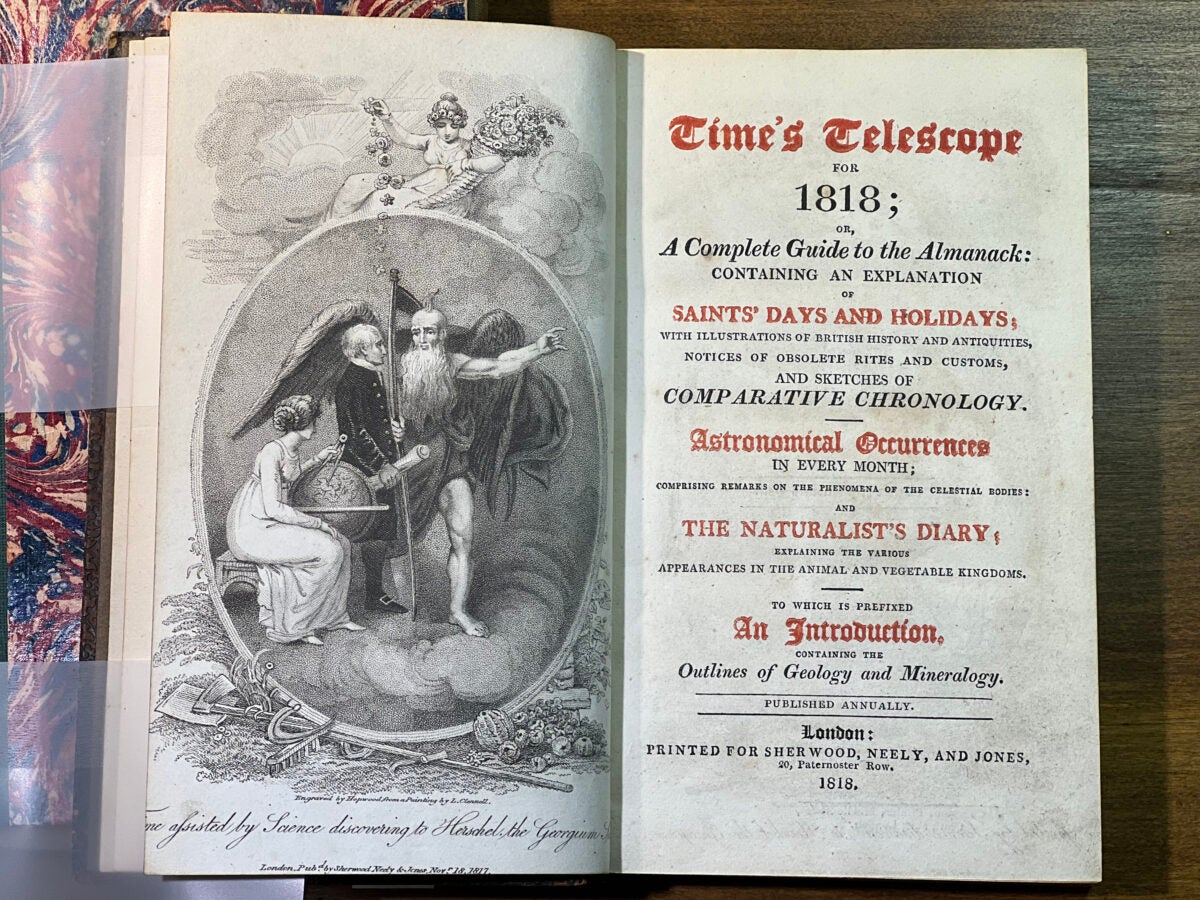

The basic format of modern almanacs took shape in Europe in the Middle Ages. Almanacs of saints’ days, church celebrations, and dates of Easter were produced by monasteries. The books provided practical information for everyday living, and included positions the Moon and planets.

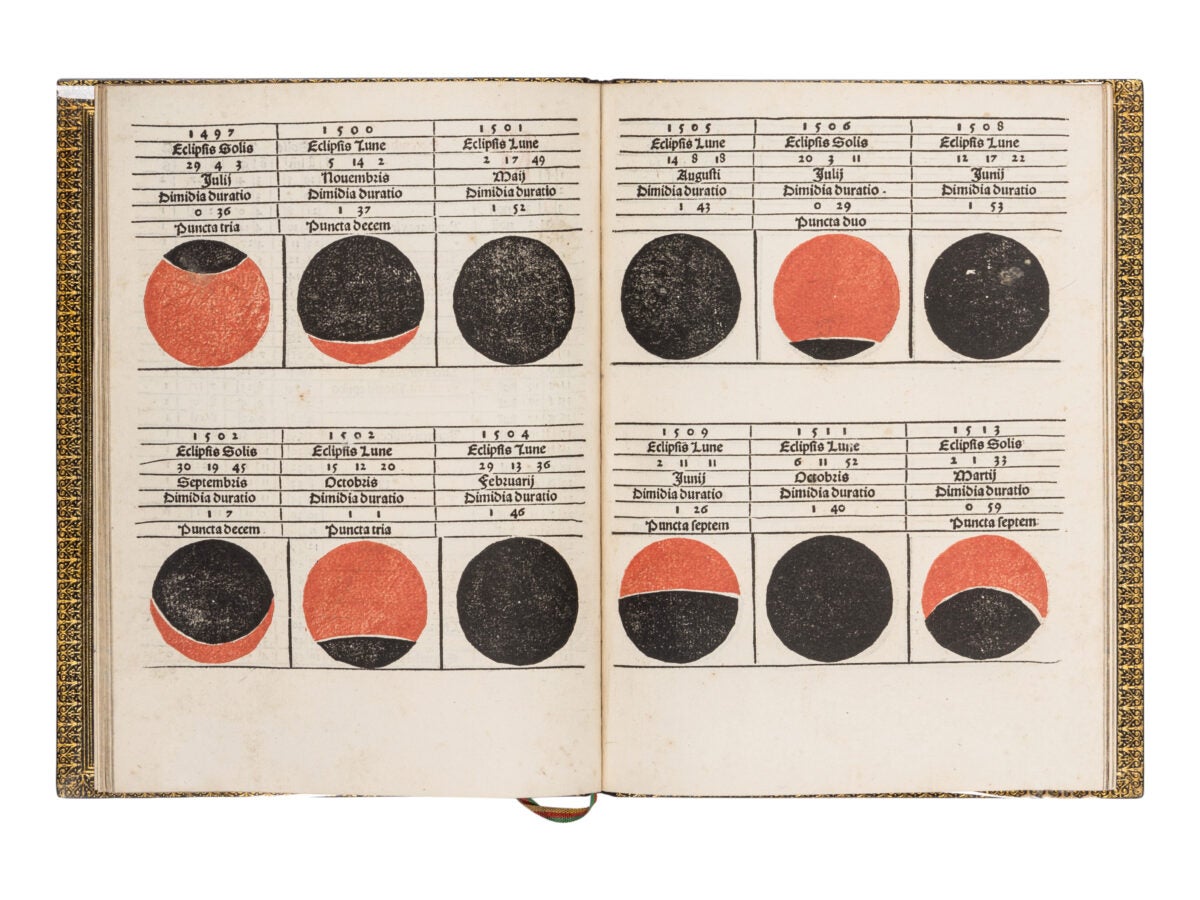

But the first true astronomical almanac was produced in the 15th century by Johannes Müller von Königsberg. Better known as Regiomontanus, the mathematician and astrologer produced his greatest work in 1474: the Calendarium and Ephemerides. Spanning over 700 pages, the massive almanac contained lunar and solar eclipse predictions, star and planet positions, and even usable paper astronomical instruments.

Regiomontanus’s almanac was intended for astrologers, but its astronomical data came in handy to sailors. On his fourth voyage to the Americas, Christopher Columbus had to beach his ships in Jamaica. The Indigenous peoples supplied food, but after six months, became fed up with the crew’s demands. Faced with starvation, Columbus consulted his copy of the Calendarium, which predicted a total lunar eclipse the night of Feb. 29, 1504. Columbus threatened to inflame the Moon if the locals didn’t cooperate. That night, the Moon rose and turned blood red, proving the “power” of Columbus and his God, and saving the Europeans.

Growth in Britain and America

In 1766, Britain commissioned the first Nautical Almanac and Astronomical Ephemeris. Since the beginning of the 18th century, the nation had been in a race to develop an accurate way to determine longitude at sea. In 1714, Parliament offered a prize of 20,000 pounds to anyone who could find a “simple and practical method for the precise determination of a ship’s longitude at sea.”

Astronomer Royal Nevil Maskelyne favored the lunar distance method. This involved measuring the angular separation between the Moon and a bright star and comparing the observation with an almanac based on Greenwich time. The key was an almanac that gave accurate positions of the Moon and bright stars.

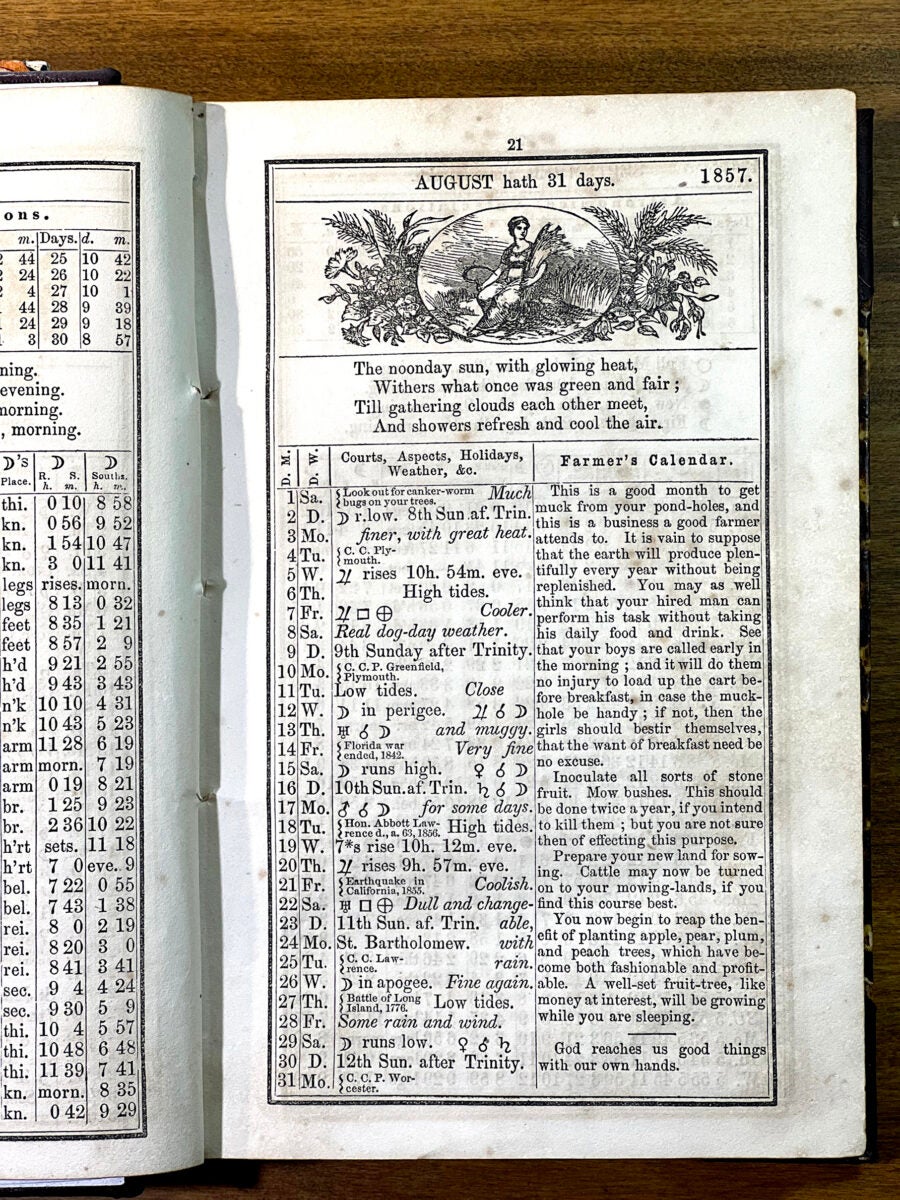

While astronomers were producing ever more accurate almanacs for navigation, there was also a need for information to help farmers, merchants, and others. As a result, publishers throughout Europe began to produce a growing number of almanacs. They ranged from books with a few pages to leatherbound volumes. By the early 19th century, these almanacs became indispensable.

Across the pond, the first colonial almanac, An Almanac for New England for the Year 1639, was written by William Pierce and printed at Harvard College. But Poor Richard’s Almanack, written and printed by Benjamin Franklin, is without a doubt the most famous American almanac. He may have gotten the idea while living in London, where he undoubtedly saw Rider’s British Merlin, a volume published in England since 1656.

Another important almanac came from Benjamin Banneker, who was born a free African American in 1731. A brilliant self-taught man most famous for surveying what would become the District of Columbia, he was also deeply interested in astronomy, and successfully predicted a solar eclipse in 1789. This may have inspired him to print the Pennsylvania, Delaware, Maryland, and Virginia Almanack and Ephemeris from 1792 to 1797.

The gold standard

The Old Farmer’s Almanac and others of its type provide lots of astronomical information, but astronomers require more.

The publication of England’s The Nautical Almanac began in 1767 in response to the need for better navigational accuracy. The American Ephemeris and Nautical Almanac appeared in 1855 and continued through 1980. In 1981, the U.S. and England joined forces to publish a single book, The Astronomical Almanac.

Most observatories and planetariums have a copy of The Astronomical Almanac on hand, or have an online subscription to its content. The amount of information it contains is staggering — more than what most people need on every aspect of astronomy.

Other astronomical almanacs are more useful to amateurs. One of the best is the Observer’s Handbook published by The Royal Astronomical Society of Canada. It contains information similar to The Astronomical Almanac, but with additional details that are helpful with planning observations.

An ephemeral guide

Almanacs are filled with astronomical data for observers, and they can serve the farmer or gardener in their yearly toil. By their nature, almanacs are ephemeral, tracing celestial movements and the passage of time.

The scholar George Lyman Kittredge wrote, “Nothing is more strictly contemporary than an almanac. … It is issued for the time being and becomes obsolete, by a natural and inevitable process, when its successor appears.” Almanacs provide insights into the past, information for the present, and a glimpse of the future.