The Cosmic Web Imager was conceived and developed by Christopher Martin from Caltech in Pasadena, California. “I’ve been thinking about the intergalactic medium since I was a graduate student,” said Martin. “Not only does it comprise most of the normal matter in the universe, it is also the medium in which galaxies form and grow.”

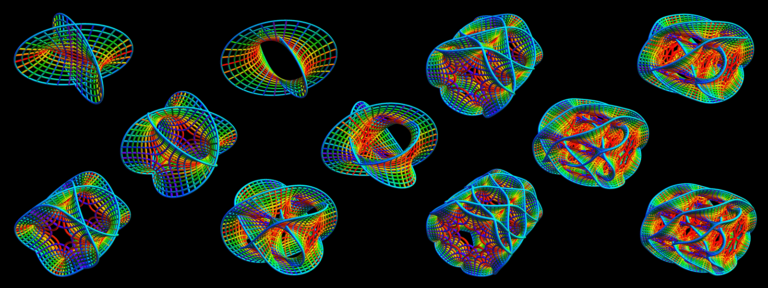

Since the late 1980s and early 1990s, theoreticians have predicted that primordial gas from the Big Bang is not spread uniformly throughout space, but is instead distributed in channels that span galaxies and flow between them. This “cosmic web” — the IGM — is a network of smaller and larger filaments crisscrossing one another across the vastness of space and back through time to an era when galaxies were first forming and stars were being produced at a rapid rate.

Martin describes the diffuse gas of the IGM as “dim matter” to distinguish it from the bright matter of stars and galaxies and the dark matter and energy that compose most of the universe. Though you might not think so on a bright sunny day or even a starlit night, fully 96 percent of the mass and energy in the universe is dark energy and dark matter, whose existence we know of only due to its effects on the remaining 4 percent that we can see — normal matter. Of this 4 percent that is normal matter, only one-quarter is made up of stars and galaxies, the bright objects that light our night sky. The remainder, which amounts to only about 3 percent of everything in the universe, is the IGM.

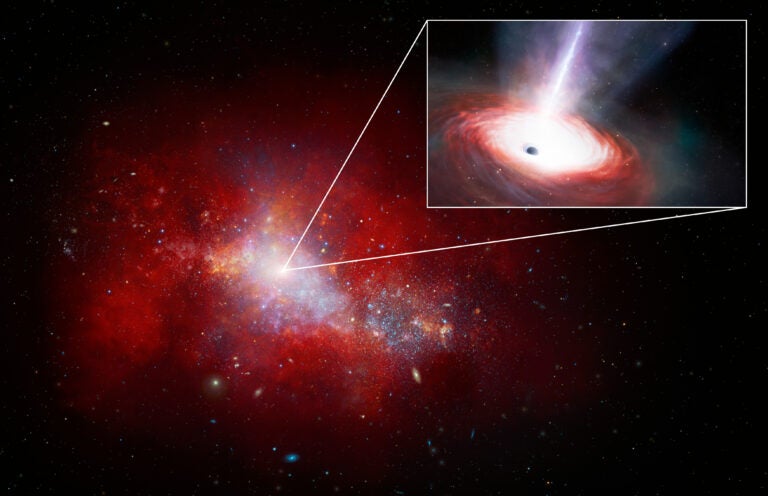

As Martin’s name for the IGM suggests, “dim matter” is hard to see. Prior to the development of the Cosmic Web Imager, the IGM was observed primarily via foreground absorption of light — indicating the presence of matter — occurring between Earth and a distant object such as a quasar — the nucleus of a young galaxy.

“When you look at the gas between us and a quasar, you have only one line of sight,” said Martin. “You know that there’s some gas farther away, there’s some gas closer in, and there’s some gas in the middle, but there’s no information about how that gas is distributed across three dimensions.”

Matt Matuszewski, a former graduate student at Caltech who helped build the Cosmic Web Imager and is now an instrument scientist at Caltech, likens this line-of-sight view to observing a complex cityscape through a few narrow slits in a wall: “All you would know is that there is some concrete, windows, metal, pavement, maybe an occasional flash of color. Only by opening the slit can you see that there are buildings and skyscrapers and roads and bridges and cars and people walking the streets. Only by taking a picture can you understand how all these components fit together and know that you are looking at a city.”

Martin and his team have now seen the first glimpse of the city of dim matter. It is not full of skyscrapers and bridges, but it is both visually and scientifically exciting.

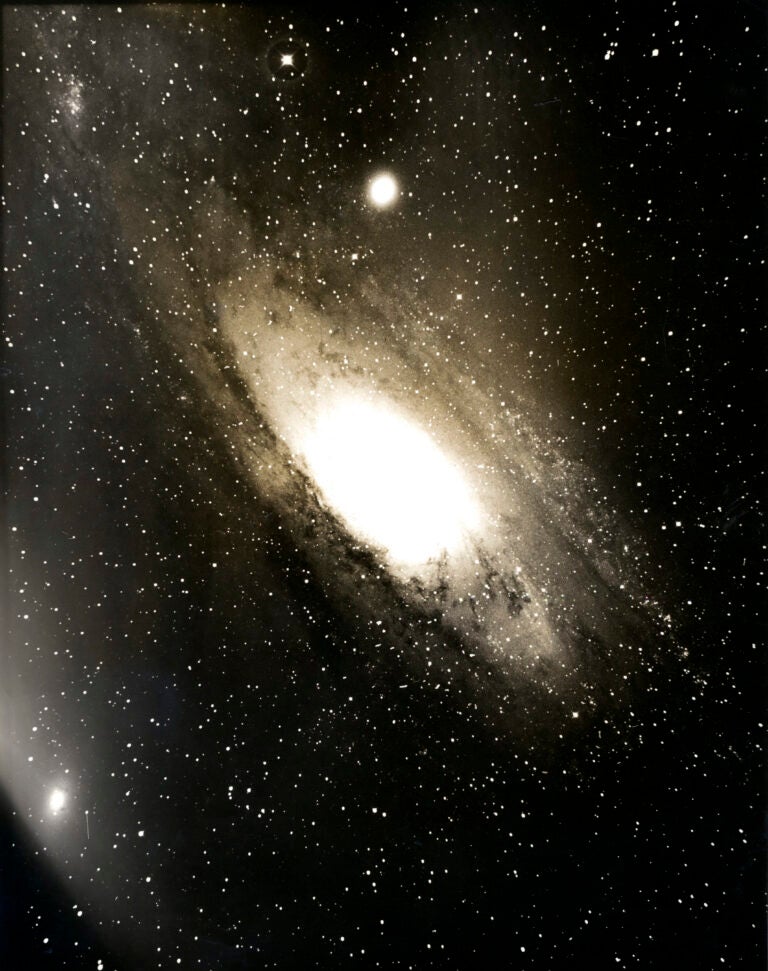

The first cosmic filaments observed by the Cosmic Web Imager are in the vicinity of two very bright objects: a quasar labeled QSO 1549+19 and a so-called Lyman-alpha blob in an emerging galaxy cluster known as SSA22. Martin chose these for initial observations because they are bright, lighting up the surrounding IGM and boosting its detectable signal.

Observations show a narrow filament, 1 million light-years long, flowing into the quasar, perhaps fueling the growth of the galaxy that hosts the quasar. Meanwhile, there are three filaments surrounding the Lyman-alpha blob with a measured spin that shows that the gas from these filaments is flowing into the blob and affecting its dynamics.

The Cosmic Web Imager is a spectrographic imager, taking pictures at many different wavelengths simultaneously. This is a powerful technique for investigating astronomical objects as it makes it possible not only to see these objects, but also to learn about their compositions, masses, and velocities. Under the conditions expected for cosmic web filaments, hydrogen is the dominant element and emits light at a specific ultraviolet wavelength called Lyman alpha. Earth’s atmosphere blocks light at ultraviolet wavelengths, so one needs to be outside Earth’s atmosphere observing from a satellite or a high-altitude balloon to observe the Lyman-alpha signal.

However, if the Lyman-alpha emission lies much farther away from us, that is, it comes to us from an earlier time in the universe, then it arrives at a longer wavelength — a phenomenon known as redshifting. This brings the Lyman-alpha signal into the visible spectrum such that it can pass through the atmosphere and be detected by ground-based telescopes like the Cosmic Web Imager.

The objects the Cosmic Web Imager has observed date to approximately 2 billion years after the Big Bang, a time of rapid star formation in galaxies. “In the case of the Lyman-alpha blob, I think we’re looking at a giant protogalactic disk,” said Martin. “It’s almost 300,000 light-years in diameter, three times the size of the Milky Way.”

The Cosmic Web Imager was funded by grants from the NSF and Caltech. Having successfully deployed the instrument at the Palomar Observatory, Martin’s group is now developing a more sensitive and versatile version of the Cosmic Web Imager for use at the W. M. Keck Observatory atop Mauna Kea in Hawaii. “The gaseous filaments and structures we see around the quasar and the Lyman-alpha blob are unusually bright. Our goal is to eventually be able to see the average intergalactic medium everywhere. It’s harder, but we’ll get there,” said Martin.

Plans are also underway for observations of the IGM from a telescope aboard a high-altitude balloon, FIREBALL (Faint Intergalactic Redshifted Emission Balloon), and from a satellite, ISTOS (Imaging Spectroscopic Telescope for Origins Surveys). By virtue of bypassing most, if not all, of our atmosphere, both instruments will enable observations of Lyman-alpha emission — and therefore the IGM — that are closer to us, that is, that are from more recent epochs of the universe.