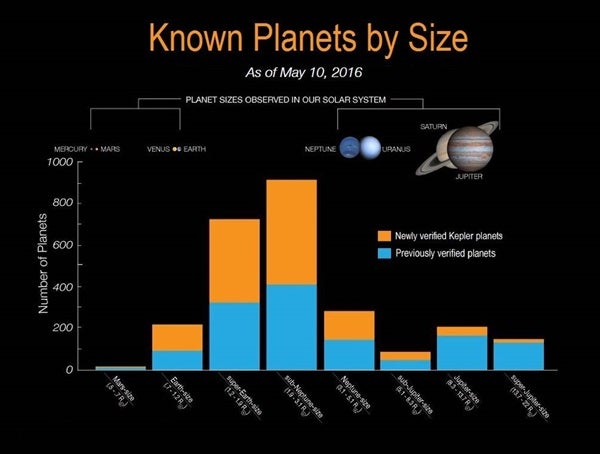

Today, researchers on NASA’s Kepler planet hunting mission didn’t announce one new interesting planet, as they usually do. Instead, they announced about 1,200 of them.

That more than doubles the number of confirmed planets in the catalog. As of yesterday, the listed number stood at 1,041 confirmations. The new planets aren’t a result of the K2 mission, though. Instead, it’s about new software that enabled Kepler researchers to parse out the signal from noise in candidate planets.

Jeff Coughlin, a SETI Institute researcher who helps NASA put together the Kepler catalog, said that the 1,284 new planets are validated to 99 percent certainty. This means that they are all almost certainly planets.

“Adding in these 1,200 really doubles our sample of really high confidence planets,” Coughlin says.

The refinement techniques account for any star in the region that might give a false transit signal, as well as accounting for the size of any transiting object to rule out image artifacts or flaws in Kepler’s imaging.

But the new software’s true strength is its ability to sort through hundreds of candidates at once.

“People have done this for single targets in the past, but it was very computationally intensive,” Coughlin said.

While Kepler has often touted finding the latest “most Earth-like planet,” or systems of planets in strange orbital configurations, the sheer volume means the researchers are still combing through the dataset for intriguing planets. The paper, published in the Astrophysical Journal today, puts the number of potentially habitable worlds in the dataset around nine total. Coughlin said the new catalog also includes long-period planets. One such planet, Kepler-1638b, has a period of 259 days, placing its year somewhere in between Venus and Earth.

Long-period planets are important because they’re more in line with what we know from our solar system. Kepler has a bias toward short period planets, those that complete an orbit within a few days. The original Kepler data set comes from a little under four years of observation. So if an alien civilization had been staring at our Sun with their own Kepler, they probably would have detected Mercury and Venus, maybe detected Earth and Mars, and not detected any of the larger planets, as some of the dips in light may have happened only twice, once, or not at all. Kepler requires three transits to prove a planet’s status as real. A total of 84 have orbital periods of longer than 100 days, with the longest orbital period at 510 days.

When something is hard to detect, “those are also the hardest ones to get telescope time to follow up on,” Coughlin says.

Natalie Batalha, a Kepler scientist with NASA Ames, said that there’s a bias toward the short periods as well just given the four year shelf life of the original Kepler data.

“The ranks start to thin as we go to longer period objects,” she said in the press conference.

Transiting planets are especially hard to find from the ground, with Timothy Morton, associate research scholar at Princeton University in New Jersey, saying, “It’s taken about 15 years of hard work for astronomers to confirm 200 transiting planets from the ground,” in a NASA press conference on the findings.

Kepler-452b, the “cousin planet” to Earth, was found by better sorting through data, allowing a 385-day-period planet to be extracted. In that case, the planet was not only Earth-like because it was similar in size, but because it had an Earth-like year. There may be others like it in the data.

“The real importance is the prime mission of Kepler, which is to find out how many planets like Earth are out there,” Coughlin says.

There’s still more work to do. For instance, there are more than 3,000 candidate planets left in the Kepler data that are believed to be possible planets. This is in addition to a list of “Kepler Objects of Interest” that’s sort of the roll call of candidates-to-be-candidates. Using the new method, 428 candidates were validated as very likely not being planets.

Most of the 1,284 validated planets are mini-Neptunes, planets at the lower limits of gas giant size. The next biggest sample is super-Earths, with some planets found that are roughly Earth sized and about as many roughly Neptune sized.

Batalha says the new refinements mark the beginning of the end for the Kepler dataset from the K1 mission.

“Kepler’s prime mission has entered its close-out stage,” she said in a press conference. “We have until October of next year to finalize our catalog.”

Further refinement techniques could find more truly Earth-sized objects, rather than the bevy of super-Earths (and mini-Neptunes and hot Jupiters) in the catalog. Both NASA’s TESS and ESA’s GAIA mission, the next generation of planet finders, will bolster the cases for some of these planets.

“This new methodology will be directly applicable to new exoplanet finders,” Batalha said.

But in the meantime, we have 1,200 more planetary neighbors. Say hi!