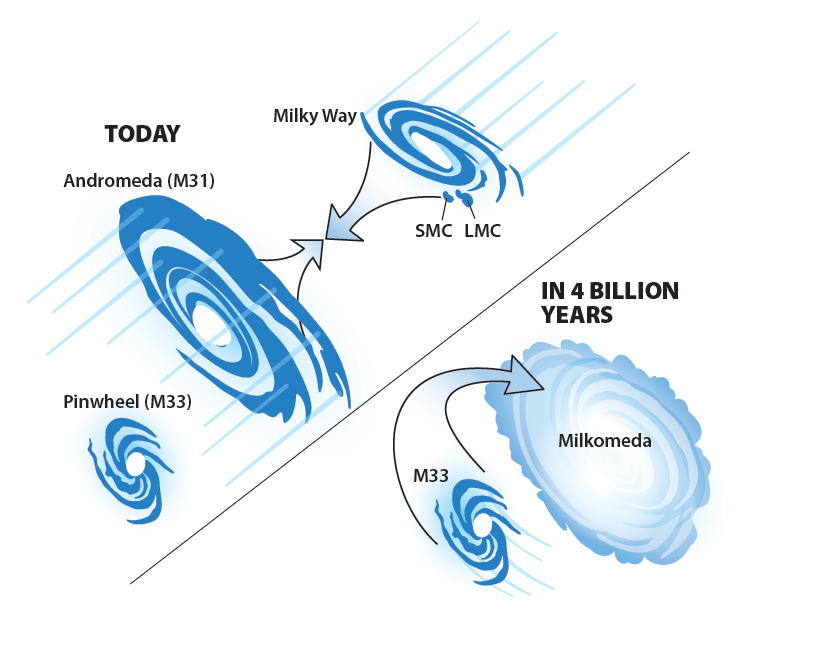

If you’ve ever attended a star party, it’s more than likely that the astronomer on site pointed out the Andromeda Galaxy (M31) — currently around 2.5 million light-years away — and mentioned that it’s expected to collide with the Milky Way Galaxy in about 4.5 billion years. But recently, an international team of astronomers posted a study on the arXiv preprint server stating that the merger of the two galaxies is far from guaranteed.

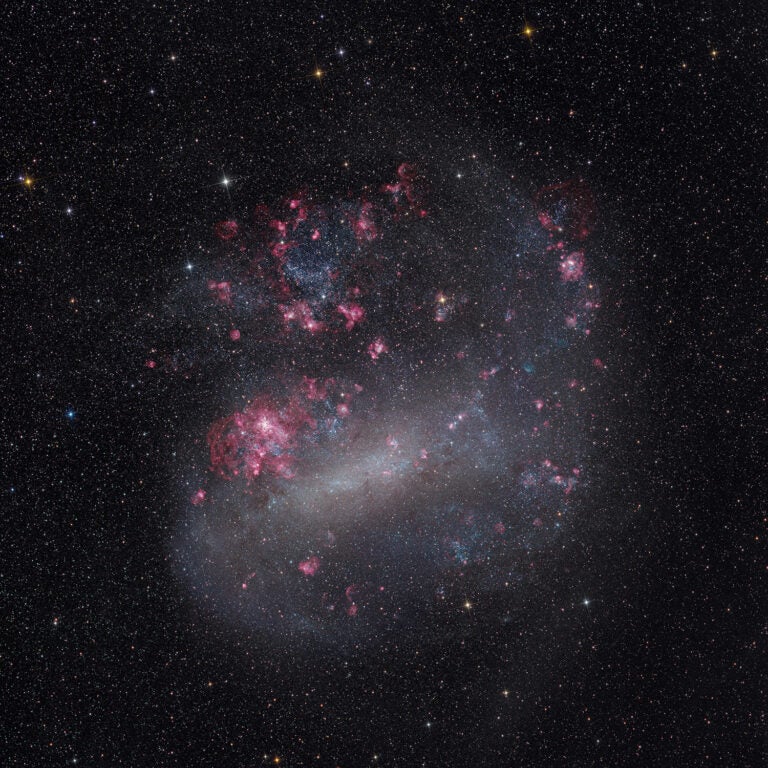

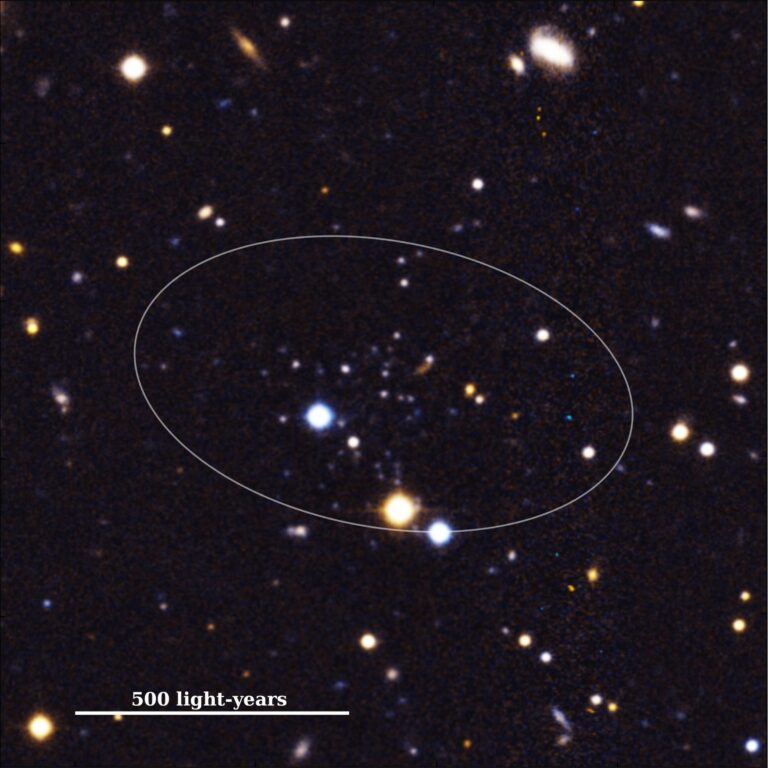

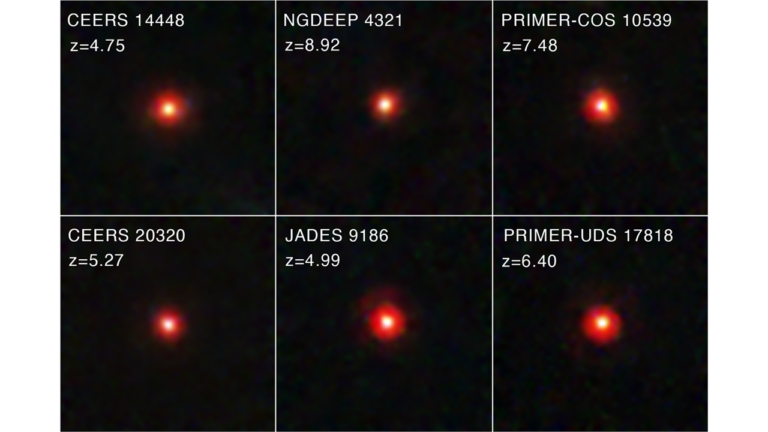

The team, led by Till Sawala of the University of Helsinki, ran simulations including four of the largest galaxies in the Local Group: Andromeda, the Milky Way, the Triangulum Galaxy (M33), and the Large Magellanic Cloud (LMC). Each combination of the multi-body system produced different results for the merger. The data came from the most updated measurements of each galaxy’s mass and proper motions made by Gaia and the Hubble Space Telescope.

Not so fast

Before Edwin Hubble determined that Andromeda was far outside the Milky way and a galaxy in its own right, it was one of many so-called spiral nebulae believed to lie within the Milky Way. But even before this discovery, astronomers had already realized that Andromeda was moving toward us. Since then, huge efforts have been made to produce the most accurate measurements of the galaxy’s properties and, in the past few decades, develop computer models to predict its titanic crash into our galaxy. Some say the first close encounter will happen in less than four billion years, while others say it’ll be after 4.5 billion years. But over the past decade or so, the consensus has hewed overwhelmingly toward a crash being inevitable.

Related: Our galaxy’s date with destruction

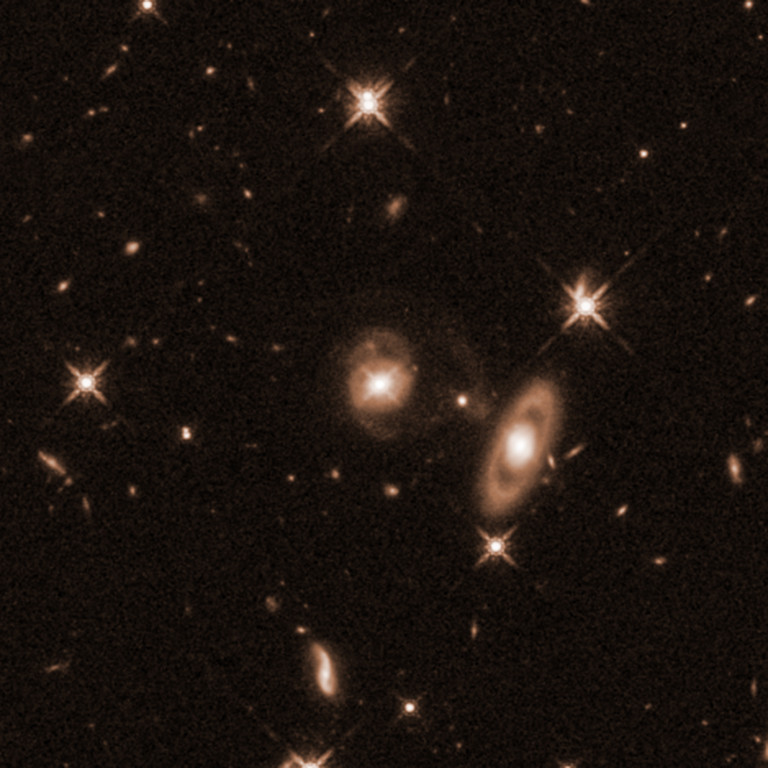

Not so fast, Sawala’s group says. The probability of the crash occurring at all — resulting in an elliptical galaxy dubbed Milkomeda — varies greatly depending on the inclusion or exclusion of either of the two other Local Group galaxies mentioned above.

The researchers chose to use a simulation developed by the Institute for Computational Cosmology at Durham University in England. The galaxies residing in the Local Group are gravitationally bound, so apart from each member’s individual parameters, the model also needs to include gravitational forces and dynamical friction — the transfer of energy through gravitational interactions, which is the dominating factor as the collision gets closer and leads to the decay of galactic orbits. However, it is important to note that even the “most accurate” measurements still have a wide range of uncertainty, so the team used a method known as Monte Carlo sampling to test tens of thousands of possibilities within those uncertainties.

It is this range of uncertainty, compounded by the inclusion of four different galaxies, that led Sawala’s group to throw up a yellow flag on a Milkomeda future.

Every little bit counts

Sawala’s team first ran the model with only the Milky Way and Andromeda, with masses of one trillion and 1.3 trillion solar masses, respectively. It showed that the two galaxies merged in less than half of the cases, mostly during the second-closest encounter. And depending on the closeness of that encounter, the time of collision was either 7.6 or eight billion years from now. “Based on the best current data, both outcomes are almost equally likely,” said the study.

To up the ante, they used a three-body system including the Triangulum Galaxy, and found that this increased the chances of collision to about two-thirds with a similar time frame as the two-body system. The model showed that M33 slowed Andromeda’s velocity relative to our galaxy, meaning that Andromeda wasn’t moving away fast enough to avoid merging.

But adding in the LMC changed things yet again, with or without M33. The simulation with just the Milky Way, Andromeda, and the LMC resulted in mergers in only a third of all the cases. But when all four of the galaxies were included in the model, the collision rate went back up to a coin toss occurring within the next 10 billion years.

Gravity — and time — will tell

Uncertainty is the biggest factor in, well, the uncertainty. The mass of the Milky Way is only known to within roughly 20 percent, and it’s only known to within 30 percent for the two smaller galaxies. Furthermore, while the individual contributions from the Local Group of galaxies’ smaller members is close to negligible, they are not when taken together, and calculating that effect is a daunting computational task — one not yet covered by Sawala’s team.

Weighing entire galaxies — their stars, dust, and invisible dark matter — and measuring their motions is a basic but still monumental task in astronomy. Gaia’s fourth data release, due in 2026, along with other new or updated surveys will help, but only to a point.

In spinning the possibilities out over eons of future time, even small ripples in the cosmic stream can have large effects. The only way to be sure might be to wait 10 billion years.