Astronomy was the basis of many key beliefs for the ancient Egyptians. They used skywatching to fix the dates of religious festivals, to predict the annual flooding of the Nile, and to count the hours of the night — when the god Ra would pilot his Sun boat on a dangerous journey through the underworld, warding off attacks and rising victorious in the east as the dawning of a new day.

But experts haven’t agreed how the ancient Egyptians saw one of the most striking features of our night sky: the dense stream of stars called the Milky Way, which we know to be the visible portion of our galaxy.

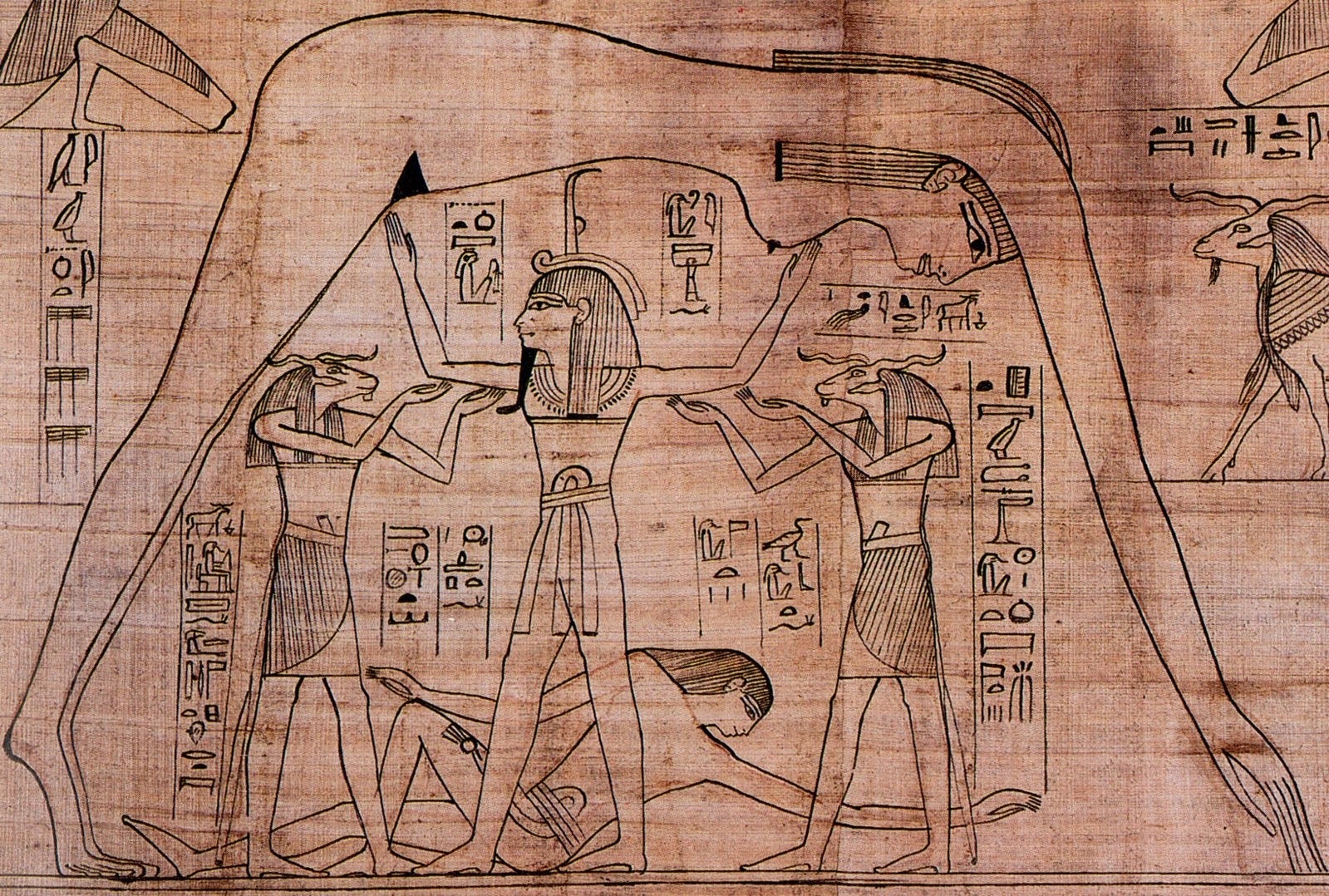

There’s evidence they associated it with the sky goddess Nut, who was often portrayed as a star-studded woman arched over her husband (and brother), the earth god Geb. But astronomers and Egyptologists have long debated just how Nut related to the Milky Way.

Now a new study steps beyond the debate and suggests that while Nut was associated with the Milky Way, her image wasn’t directly embodied there. Instead, the ancient Egyptians may have seen Nut’s outstretched arms in the Milky Way during the northern winter months, and seem to have believed it outlined her torso or backbone in summer.

“I would say that it’s a figurative association,” astrophysicist Or Graur tells Astronomy.

In a study published April 2 in the Journal of Astronomical History and Heritage, Graur argues the ancient Egyptians saw different aspects of Nut in the Milky Way in different seasons, and that there was no one-to-one map of her body onto the stars. “It’s a bit more subtle,” he says.

Graur, of the University of Portsmouth in the U.K., is the author of Supernova — his usual area of study — and encountered the myth of Nut during his research for Galaxies, a book to be published in August.

He says he realized Nut’s impact after visiting the Fitzwilliam Museum at the University of Cambridge with his young daughters, where they saw a portrayal of Nut on an ancient Egyptian coffin. Graur’s daughters were taken with Nut’s image, so to find out more, he researched the ancient Egyptian myths about the goddess.

Graur’s research turned up scientific papers about Nut and her association with the Milky Way, including one from 1992 by astronomer Ronald A. Wells. But Graur says he found the associations of Nut with particular parts of the sky in those papers unconvincing, mainly because they tried to associate Nut with specific stars; Wells, for example, suggests her head must have been near the constellation Gemini.

However, the ancient Egyptians believed Nut swallowed the Sun each sunset and gave birth to it each dawn, which meant that her head and loins always had to be at the western and eastern horizons respectively, Graur says.

And since the Milky Way changes positions in the sky over the course of a year, so that it effectively spans diagonally opposite horizons, Graur reasons that Nut’s head and loins couldn’t be associated with specific stars.

To investigate, Graur used the software planetariums Cartes du Ciel and Stellarium to reproduce the night sky seen from Giza in 1880 B.C.E. — roughly the time of the Middle Kingdom, which is considered a golden age of ancient Egyptian culture.

He then compared the star maps with ancient Egyptian texts, including the Pyramid Texts from early tombs at Saqqara, the Coffin Texts written mainly during the Middle Kingdom, and the Book of Nut, a relatively recent source at about 2,000 to 3,000 years old.

From these, Graur determined that while the ancient Egyptians linked Nut to the Milky Way, there wasn’t a direct association between parts of her body and parts of the sky.

Instead, he found the strongest association in their winter view of the Milky Way, when it spanned the night sky from the southeast to the northwest and was supposed to represent her outstretched arms leading the dead into the sky.

In summer, however, the Milky Way spanned the night sky from the northeast to the southwest; Graur says this may have represented Nut’s torso or backbone, the path by which she restored the Sun each morning — a link reinforced by some southern African legends.

“These different representations highlight specific attributes of the goddess,” he says. “You can think of the Milky Way as a spotlight, shining up in the sky and illuminating parts of her body.”

Astronomer E.C. Krupp, the director of the Griffith Observatory in Los Angeles and the author of Echoes of the Ancient Skies: The Astronomy of Lost Civilizations, says Graur brings “a fresh perspective to an enduring problem — the place of the Milky Way in the celestial metaphors of ancient Egypt — and provides some much-needed clarity.”

Krupp, who wasn’t involved in the study, adds Graur “wisely avoids turning Nut into some kind of astronomical acrobatic contortionist, to coordinate her different and sometimes contradictory aspects.”

Instead, he “leaves room for the goddess to breathe and renew the celestial realm through his treatment of the Milky Way as a visible sign of her presence and nature, and not as the actual goddess,” Krupp says.