Brown dwarfs, thought just a few years ago to be incapable of emitting any significant amounts of radio waves, have been discovered putting out extremely bright “lighthouse beams” of radio waves, much like pulsars. A team of astronomers made the discovery using the National Science Foundation’s Very Large Array (VLA) radio telescope.

“These beams rotate with the brown dwarf, and we see them when the beam passes over the Earth. This is the same way we see pulses from pulsars,” said Gregg Hallinan of the National University of Ireland, Galway. “We now think brown dwarfs may be a missing link between pulsars and planets in our own Solar System, which also emit, but more weakly,” he added.

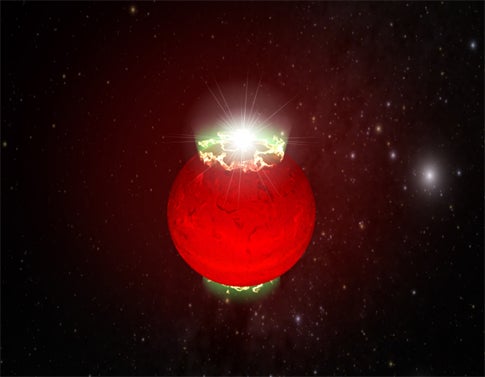

Brown dwarfs are enigmatic objects that are too small to be stars but too large to be planets. They are sometimes called “failed stars” because they have too little mass to trigger hydrogen fusion reactions at their cores, the source of the energy output in larger stars. With roughly 15 to 80 times the mass of Jupiter, the largest planet in our Solar System, brown dwarfs were long thought to exist. However, it was not until 1995 that astronomers were able to actually find one. A few dozen are known today.

In 2001, a group of summer students at the National Radio Astronomy Observatory used the VLA to observe a brown dwarf, even though seasoned astronomers had told them that brown dwarfs were not observable at radio wavelengths. Their discovery of a strong flare of radio emission from the object surprised astronomers, and the students’ scientific paper on the discovery was published in the prestigious scientific journal Nature.

Hallinan and his team observed a set of brown dwarfs with the VLA last year, and found that three of the objects emit extremely strong, repeating pulses of radio waves. They concluded that the pulses come from beams emitted from the magnetic poles of the brown dwarfs. This is similar to the beamed emission from pulsars, which are super dense neutron stars, and much more massive than brown dwarfs.

The characteristics of the beamed radio emission from the brown dwarfs suggest that it is produced by a mechanism also seen at work in planets, including Jupiter and Earth. This process involves electrons interacting with the planet’s magnetic field to produce radio waves that are amplified by natural masers, the same way a laser amplifies light waves.

“The brown dwarfs we observed are between planets and pulsars in the strength of their radio emissions,” said Aaron Golden, also of the National University of Ireland, Galway. “While we don’t think the mechanism that’s producing the radio waves in brown dwarfs is exactly the same as that producing pulsar radio emissions, we think there may be enough similarities that further study of brown dwarfs may help unlock some of the mysteries about how pulsars work,” he said.

While pulsars were discovered 40 years ago, scientists still do not understand the details of how their strong radio emissions are produced.

The brown dwarfs rotate at a much more leisurely pace than pulsars. While pulsars rotate and produce observed pulses several times a second to hundreds of times a second, the brown dwarfs observed with the VLA are showing pulses roughly once every two to three hours.