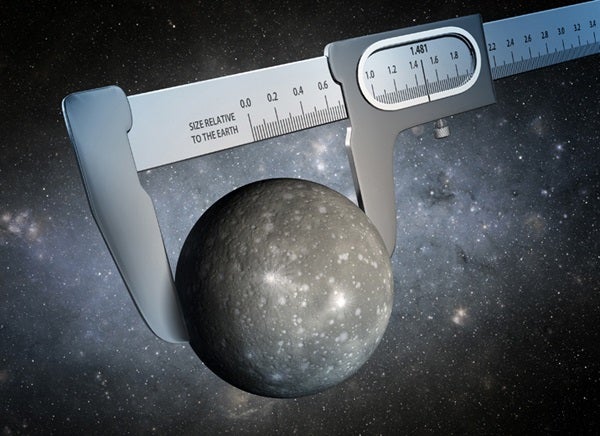

The findings confirm Kepler-93b as a “super-Earth” that is about 1.5 times the size of our planet. Although super-Earths are common in the galaxy, none exist in our solar system. Exoplanets like Kepler-93b are therefore our only laboratories to study this major class of planet.

With good limits on the sizes and masses of super-Earths, scientists can finally start to theorize about what makes up these weird worlds. Previous measurements by the Keck Observatory in Hawaii had put Kepler-93b’s mass at about 3.8 times that of Earth. The density of Kepler-93b, derived from its mass and newly obtained radius, indicates the planet is in fact very likely made of iron and rock, like Earth.

“With Kepler and Spitzer, we’ve captured the most precise measurement to date of an alien planet’s size, which is critical for understanding these far-off worlds,” said Sarah Ballard from the University of Washington in Seattle.

“The measurement is so precise that it’s literally like being able to measure the height of a 6-foot-tall person to within three-quarters of an inch — if that person were standing on Jupiter,” said Ballard.

Kepler-93b orbits a star located about 300 light-years away, with approximately 90 percent of the Sun’s mass and radius. The exoplanet’s orbital distance — only about one-sixth that of Mercury’s from the Sun — implies a scorching surface temperature around 1400° Fahrenheit (760° Celsius). Despite its newfound similarities in composition to Earth, Kepler-93b is far too hot for life.

To make the key measurement about this toasty exoplanet’s radius, the Kepler and Spitzer telescopes each watched Kepler-93b cross, or transit, the face of its star, eclipsing a tiny portion of starlight. Kepler’s unflinching gaze also simultaneously tracked the dimming of the star caused by seismic waves moving within its interior. These readings encode precise information about the star’s interior. The team leveraged them to narrowly gauge the star’s radius, which is crucial for measuring the planetary radius.

Spitzer, meanwhile, confirmed that the exoplanet’s transit looked the same in infrared light as in Kepler’s visible-light observations. These corroborating data from Spitzer, some of which were gathered in a new precision-observing mode, ruled out the possibility that Kepler’s detection of the exoplanet was bogus, or a so-called false positive.

Taken together, the data boast an error bar of just 1 percent of the radius of Kepler-93b. The measurements mean that the planet, estimated at about 11,700 miles (18,800 kilometers) in diameter, could be bigger or smaller by about 150 miles (240km), the approximate distance between Washington, D.C., and Philadelphia.

Spitzer racked up a total of seven transits of Kepler-93b between 2010 and 2011. Three of the transits were snapped using a “peak-up” observational technique. In 2011, Spitzer engineers repurposed the spacecraft’s peak-up camera, originally used to point the telescope precisely, to control where light lands on individual pixels within Spitzer’s infrared camera.

The upshot of this rejiggering: Ballard and her colleagues were able to cut in half the range of uncertainty of the Spitzer measurements of the exoplanet radius, improving the agreement between the Spitzer and Kepler measurements.

“Ballard and her team have made a major scientific advance while demonstrating the power of Spitzer’s new approach to exoplanet observations,” said Michael Werner from NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, California.