About 4 billion years ago, the young planet would have had enough water to cover its entire surface in a liquid layer about 460 feet (140 meters) deep, but it is more likely that the liquid would have pooled to form an ocean occupying almost half of Mars’s northern hemisphere and in some regions reaching depths greater than 1 mile (1.6 kilometers).

“Our study provides a solid estimate of how much water Mars once had by determining how much water was lost to space,” said Geronimo Villanueva from NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland. “With this work, we can better understand the history of water on Mars.”

The new estimate is based on detailed observations of two slightly different forms of water in Mars’s atmosphere. One is the familiar form of water made with two hydrogen atoms and one oxygen — H2O. The other is HDO, or semi-heavy water, a naturally occurring variation in which one hydrogen atom is replaced by a heavier form called deuterium.

As the deuterated form is heavier than normal water, it is less easily lost into space through evaporation. So the greater the water loss from the planet, the greater the ratio of HDO to H2O in the water that remains.

The researchers distinguished the chemical signatures of the two types of water using ESO’s VLT in Chile along with instruments at the W. M. Keck Observatory and the NASA Infrared Telescope Facility in Hawaii. By comparing the ratio of HDO to H2O, scientists can measure by how much the fraction of HDO has increased and thus determine how much water has escaped into space. This in turn allows the amount of water on Mars at earlier times to be estimated.

In the study, the team mapped the distribution of H2O and HDO repeatedly over nearly six Earth years — equal to about three Mars years — producing global snapshots of each, as well as their ratio. The maps reveal seasonal changes and microclimates, even though modern Mars is essentially a desert.

“I am again overwhelmed by how much power there is in remote sensing on other planets using astronomical telescopes,” said Ulli Kaeufl of ESO. “We found an ancient ocean more than 100 million kilometers [60 million miles] away!”

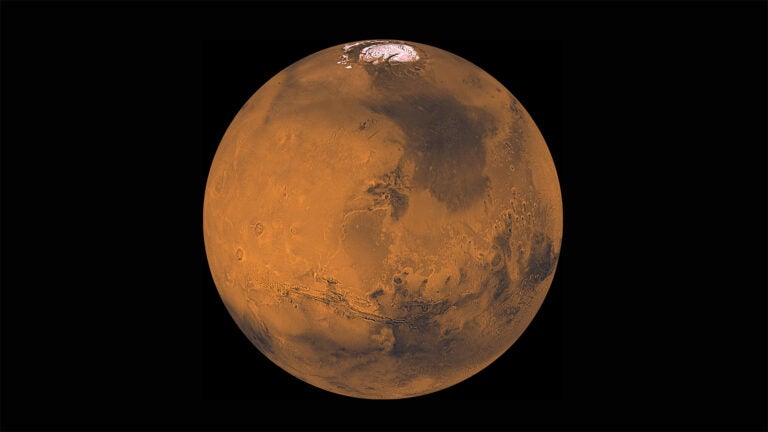

The team was especially interested in regions near the north and south poles because the polar ice caps are the planet’s largest known reservoir of water. The water stored there is thought to document the evolution of Mars’s water from the wet Noachian period, which ended about 3.7 billion years ago, to the present.

The new results show that atmospheric water in the near-polar region was enriched in HDO by a factor of seven relative to Earth’s ocean water, implying that water in Mars’ permanent ice caps is enriched eightfold. Mars must have lost a volume of water 6.5 times larger than the present polar caps to provide such a high level of enrichment. The volume of Mars’ early ocean must have been at least 4.8 million cubic miles (20 million cubic km).

Based on the surface of Mars today, a likely location for this water would be the Northern Plains, which have long been considered a good candidate because of their low-lying ground. An ancient ocean there would have covered 19 percent of the planet’s surface; by comparison, the Atlantic Ocean occupies 17 percent of the Earth’s surface.

“With Mars losing that much water, the planet was very likely wet for a longer period of time than previously thought, suggesting the planet might have been habitable for longer,” said Michael Mumma from Goddard Space Flight Center.

It is possible that Mars once had even more water, some of which may have been deposited below the surface. Because the new maps reveal microclimates and changes in the atmospheric water content over time, they may also prove to be useful in the continuing search for underground water.