When Mariner 9 entered orbit in 1971, it painted a slightly brighter picture. Sure, there was no surface water right now, but signs of dry riverbeds hinted at water in the past. Scientists began to understand that, however sterile it currently appears, Mars is still an active world of dust storms, fog, and carbon dioxide hazes. There was more than meets the eye, and Vikings 1 and 2 intended to find out what that was.

Each Viking lander included an astrobiology lab. Three experiments were meant to test for microbial life on Mars. Two of the three showed nothing, but the third produced strange and inconclusive results, revealing trace evidence for some kind of metabolic activity despite the nil results from the other experiments.

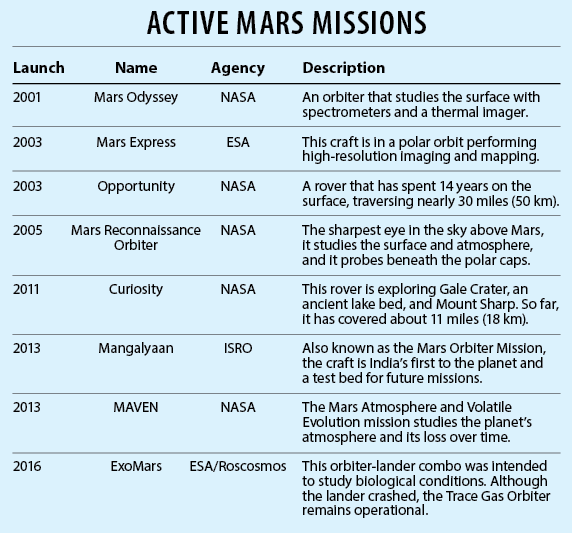

After the Viking successes of the mid-1970s, Mars exploration crept to a standstill for two decades. It’s a stark contrast to the situation today, when multiple missions are dissecting the planet from several angles.

Water, water everywhere

And it seems that every few years, these missions produce headlines declaring, “Water found on Mars.” Sometimes, a few months later, the scientific community and media turn heel: “Water not found on Mars after all.” A volley back and forth ensues. Often, the debate ends in a stalemate. But the gradual accumulation of evidence paints two different pictures for water on Mars: its past abundance, and its present possibility.

Mars Global Surveyor — which arrived in 1997, becoming the first successful mission to the planet since Viking — discovered gullies. On Earth, water typically carves such features. But Mars’ current atmosphere is much too thin for water to survive on the surface for long, so a contentious debate has developed as to what causes the gullies. Some scientists think dry ice or natural sedimentary movements could be at the root; others think seasonal flows of water could stick around just long enough to create the features. The orbiter also found evidence for subsurface glaciers and old lake beds.

Mars Odyssey and Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter (MRO), both still operating after more than a decade circling the planet, have discovered their share of intriguing geologic features. MRO famously found “recurring slope lineae,” brine-filled fluids that some researchers identify as seasonal flows of water, albeit in a salty slush that eventually dries into toxic salts — far from friendly to life. Odyssey has mapped several regions where water ice seems to exist just below the martian surface, out of reach of the Sun’s sublimating gaze.

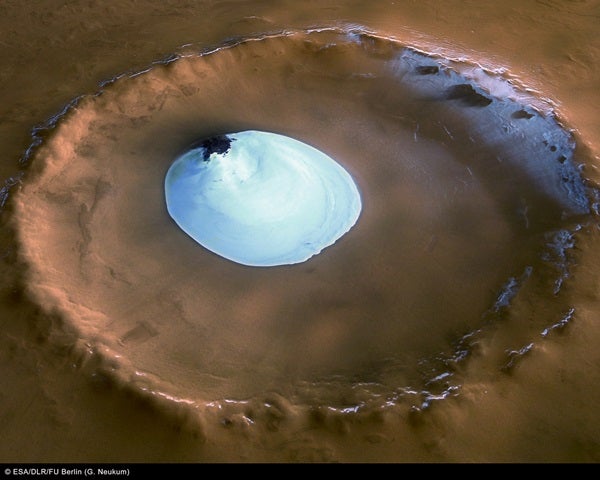

But the biggest gains arguably have come from landers and rovers. Despite some notable failures — Deep Space 2, Mars 96, Mars Polar Lander, and Beagle 2 — the bulk of the landing missions in the past 20 years have been unqualified successes. It started with Mars Pathfinder, whose Sojourner probe proved the viability of rovers on Mars in 1997. The Phoenix lander, which touched down in 2008, found abundant water ice near the north pole of Mars.

In 2007, the Spirit rover found bizarre structures made of opaline silica on the floor of Gusev Crater. On Earth, such features appear as microbial colonies near geysers, though scientists are loath to make the correlation without further evidence. The two most impressive rovers, the ongoing Opportunity and Curiosity, have spent several years exploring craters and ancient lake beds, all but confirming that Mars was a lush water world billions of years ago. In fact, Opportunity has been exploring Mars since 2004 after being given an initial 90-day mission. (Its twin, Spirit, lasted “only” until 2011.)

But where did the water go?

In order to have water on the surface, Mars needs a much thicker atmosphere. So what happened?

NASA’s MAVEN mission has gradually pieced the story together. The orbiter, which reached Mars in 2014, grazes the planet’s atmosphere to study its history. It has found that Mars likely lost its magnetic field long ago. Because of this, the solar wind had unlimited access to strip away much of the atmosphere. When that happened, some of the surface water froze underground, but most of it turned into vapor and escaped the planet entirely, turning it from a water world into a cold desert.

Besides the discovery of water and atmospheric loss, planetary probes have turned up other interesting bits about Mars in the past 45 years. For instance, while Mars’ two small moons, Phobos and Deimos, were once thought to be captured asteroids, some scientists now suspect they may have coalesced from debris launched into orbit after an asteroid impact with the planet. In addition, it appears Phobos one day will come close enough to Mars to get ripped apart and briefly form a ring around the planet.

What’s desperately needed is a new orbiter. The orbiters that serve as primary points of contact between Mars’ surface and Earth are 13 and 17 years old, and they are not guaranteed to survive far into the next decade.

All of these explorations are helping scientists build a comprehensive — and sometimes puzzling — picture of Mars. In some ways, we were already assembling our present view of Mars at Astronomy’s founding in 1973. But in so many other ways, we were just scratching the surface.