T his is the season when animals and insects, fully freed from winter somnolence, frolic around us. Is extraterrestrial life frolicking too? Astronomers keep searching.

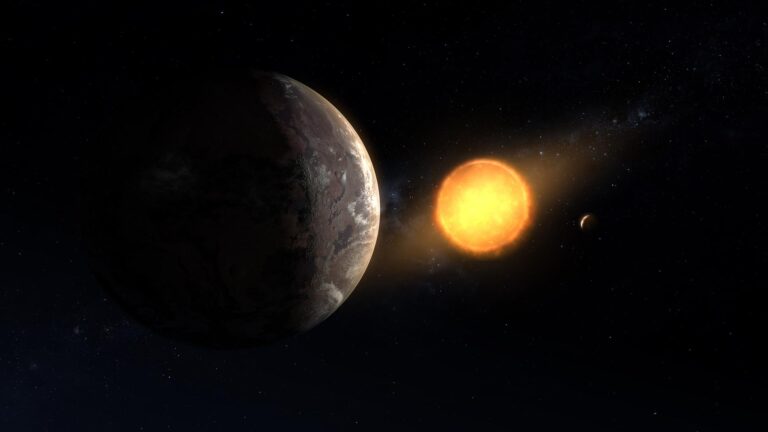

One recent estimate indicates our galaxy contains 8.8 billion Earth-sized planets located in their stars’ “habitable zones,” meaning the right distance for surface liquid water to exist. Logically, E.T.s seem certain.

But what do we really know?

It’s an old joke in research circles that if you want your presentation graph to show an impressive straight line, draw it using only two data points! Well, when it comes to seeking extraterrestrial life, science possesses one information point: Earth alone. What kind of graph can we draw given a single data point?

We desperately need another. So, if scientists find life under the martian surface or swimming through the oceans of Jupiter’s moon Europa, it would change everything. If life exists on two worlds in the same solar system, then the sky’s the limit. On the other hand, if Europa’s warm briny oceans, built-in energy source, and periodic influx of comets containing amino acids have failed to produce any life after billions of years of such friendly conditions, this too would be revelatory. Europa may thus be the key to the entire puzzle.

Europa brings up other issues as well. Astronomers always seek planets lying within their star’s habitable zone. Yet the realm of Jupiter, which lies far outside that friendly district, remains extraterrestrial life’s likeliest location. This suggests the whole habitable zone business may be a fiction borne of human unimaginativeness.

We may have handcuffed ourselves to additional fictions. Life inhabits Earth’s surface, so we seek out similar locations for extrasolar E.T.s. But why shouldn’t other worlds have their life teeming everywhere except the surface, where sterilizing radiation or a brutal vacuum is likeliest? Like that habitable zone restriction, this may be another Earth-centric prejudice. Moreover, any alien bodies that lack electrons — perhaps structured of dark matter — would be utterly invisible. We’d never see those critters.

A deeper and more controversial issue is the nature of life itself. This goes way beyond our carbon- and water-based biases. Our standard assumption is that the cosmos is a mixture of the living and the nonliving. But many primitive cultures such as early Native Americans, not to mention early Greeks like Aristotle, regarded the cosmos as eternal, animated, and alive. Could everything be a form of life? The Gaia hypothesis of Earth as a single intelligent entity has many adherents. Why stop there?

THE WHOLE HABITABLE ZONE BUSINESS MAY BE A FICTION BORNE OF HUMAN UNIMAGINATIVENESS.

Now, earlier civilizations that lived more “naturally” didn’t necessarily have monopolies on wisdom. Superstition often trumped perspicacity. The ancient widespread “all is one” viewpoint had undeniable aesthetic appeal, but until modern versions like stem cell and cloning guru Dr. Robert Lanza’s biocentrism came along, the notion that nature and the observer are intertwined lacked scientific support. This has changed somewhat in recent years.

Granted, it sounds wacky that the universe and awareness may be correlative. When famed 20th-century physicist John Wheeler said, “No phenomenon is a real phenomenon until it is an observed phenomenon,” he was giving voice to decades of increasing quantum mechanical uneasiness that started with the bewildering double-slit experiment, which questions whether the observer and the external world are truly independent.

George Berkeley, the 18th-century philosopher for whom the California city and campus were named, liked to say that the only things we can perceive are our perceptions. We merely assume a separate objective cosmos independent of our awareness. This issue fascinated Albert Einstein and his friends, too.

In the current Royal Astronomical Society of Canada’s Observer’s Handbook, physicist Roy Bishop says things like, “Our visual world with its brightness and colours occurs within our skull. … We are part of the rainbow, its most beautiful part.” And physiology textbooks state that all those objects you assume are visually “out there” in front of you, separate from your body, are actually located inside your brain. Yes, that’s the inside of your brain out there.

Unfortunately, our logic system cannot deal with this. You can easily visualize your skull dwelling within the universe, but can you picture the cosmos simultaneously existing within your skull? It’s a paradox that implies solipsism, a single living cosmos. But if true, then nothing is nonliving.

Whether you “get” all this, are stupefied by it, or perhaps dismiss it as a branch of metaphysics or philosophy, rest assured some no-nonsense physicists like Bishop and medical doctors like Lanza take it seriously enough to consider the cosmos as an aspect of life.

Just because this view jibes with half of the world’s religions, western mystics like William Blake, and many thinkers through the centuries doesn’t give it a free pass. They could all be wrong. We should, however, remain aware that there’s more to this extraterrestrial life business than such endlessly repeated issues as how many Earth-sized worlds are out there.

That’s just the topmost layer. Look deeper, and the subject gets wonderfully juicy.

Contact me about my strange universe by visiting http://skymanbob.com.