One of the world’s most famous astronomical clocks looms over a side street in the old city of Prague, with a complex astronomical dial, multiple myths, and a recent scandal — all worth investigating.

The Gothic-style tower was built during the 14th century to warn townsfolk of danger ranging from fires to invasions, and later connected to the Old Town Hall. In the early 15th century, the sentinel expanded beyond just a tower when the clock and astronomical dial were added. Decorative statues and a calendar plate followed over the decades.

The astronomical clock has been repaired many times throughout the years, and the moving gears and components restored. On May 8, 1945, the tower nearly collapsed during Nazi attacks in World War II. The Old Town Hall and nearby buildings burnt, along with a few wooden sculptures adorning the tower. After three years, local citizens banded together to repair the machinery, add new sculptures, and set the Prague clock into motion once again.

The Apostle March

The astronomical clock tower, known as the Orloj (pronounced Or’-loy) by the local Czechs, is comprised of three sections: windows for the 12 Apostles to behold the public, an astronomical dial, and a calendar dial. Let’s examine each section in greater detail.

The 12 Apostles figures parade around the clock top every hour as two blue trapdoors open, allowing them to gaze upon people in the town square for a few moments. To see the figures – and inner portions of the astrolabe – up close, one can purchase tickets for a self-guided tour. This includes a climb to the top of the tower where one can observe the complex gears which rotate the Apostles, permitting two at once to behold the public.

The Astronomical Clock

The next section of the Orloj is the astronomical clock. The face is a series of complex dials and lines of positions, also known as an astrolabe, or a flattened planetarium. Astrolabes are mechanical instruments showcasing heavenly bodies’ positions, which enable navigators to measure their latitude on the surface of Earth, day or night. (While it may seem ancient, the concept is still used today: The author used U.S. Naval Observatory almanac tables to find the Sun, Moon, and Polaris via a sextant as an Air Force navigator.)

For the Prague astronomical tower, the Sun, Moon, and local horizons are displayed. Find the Moon’s line of position by the spotting the black hand with a silver and/or black orb – the color scheme represents the lunar phases. During a Full Moon, the orb will be completely silver. As the Moon rotates, more black phase will be shown until completely dark, as in a New Moon. The Moon also moves on the clock face counterclockwise and requires 24 hours, 50 minutes, and 28 seconds to travel once around the face, as the Moon rises each day nearly 50 minutes later.

The Sun, depicted as a brilliant star, travels around the face clockwise. The various colors on the dial represent daylight or nighttime: Blue represents day, while red on the face highlights sunrise on the left, and sunset on the right. Finally, black depicts nighttime, opposite the blue horizon.

Related: A brief history of time: What is it and how do we define it?

The clock face displays four different times, some recognizable and others ancient. Beginning on the outer edge of the dial, in deep blue, is Bohemian (or Old Czech) time shown in the Gothic numbers. The day consists of 24 hours and starts from the sunset (rather than midnight, as we’d use today). Bohemian time was utilized by Holy Roman Emperor Charles IV, and is pointed to here by the golden hand.

Next is Central European Time (CET) Zone, two sets of 12 hours shown in Roman numerals inside the Bohemian time numbers. CET is also indicated by the golden Sun hand.

Third is Babylonian (or Arabian) time, the oldest time displayed on the astronomical dial. Babylonian time, displayed in black Arabic numerals, separates the time between sunrise and sunset; that’s why there are only 12 hours.

Finally, we have star time, or sidereal time. Sidereal uses the time it takes Earth to rotate once on its axis and return facing a distant star. Its time is 23 hours and 56 minutes, four minutes shorter than a solar day. A solar day is defined by when the Sun is overhead at noon, which must account for the Earth tracking one degree, or day, along its orbit around the Sun and hence is longer. Follow the little golden star among the Roman numerals for sidereal time. Now you are prepared to tell time via the stars or even back in the Middle Ages.

Examining the astronomical clock further, one can spot a smaller dial within the entire face. The smaller circle is the zodiac, divided into 12 signs and connected with the position of the Sun. Thus, as the Sun voyages around the astronomical dial, our star also points out the current zodiacal sign.

This complex astronomical piece is an impressive feat of craftsmanship and science. Imagine establishing such an astronomical clock in a time with no computers, smartphones, or other displays – and keeping it operating for over 600 years! No wonder the Prague citizens are proud of their heavenly timepiece.

The Calendar

The final component of the Orloj is the calendar plate. On the blue outer circle is a Church calendar, listing each day with the names of 365 saints. Working inward, there are 12 symbolic monthly paintings. Next are smaller images representing zodiac signs, like Aquarius. In the middle is the city of Prague emblem.

Myths & Legends

There are numerous myths attributed to the Orloj. According to one myth, the skeleton located near the upper-right side of the astrolabe, represents an ominous omen. If the Orloj stops running for a lengthy time, Czechs will suffer bad times. The skeleton will nod its head. The only way to undo the situation is reset the Orloj into motion. Then a boy born on a New Year’s Eve must sprint from the Týn Church across the whole town square to the town hall. He has to run very swiftly to arrive before the last strike of the clock. If he makes it, he will quell the skeleton’s evil power.

A second myth highlights positive vibes – a hope. There are two small windows above the astronomical clock, the Apostle doors. The windows provided light leading to a medieval jail. According to the myth, a knight was captured and awaiting his execution. One day, the knight peered out of one window as the clock started to strike at top of the hour, and a sparrow flew towards the skeleton’s open mouth. When the skeleton closed his jaws, the bird became trapped inside. The sparrow had to wait an hour until the skeleton opened his jaw again, able to fly free. When the knight witnessed the sparrow fly free, he believed he would go free as well. Sure enough, the knight received a pardon just in time. Thus, the scary skeleton also became the symbol of hope.

Today, the skeleton rings a bell, acting as the grim reaper, reminding all we have limited time. Next to the astrolabe, other figures set in motion during the top of each hour. From left to right the are Vanity, Avarice, and Lust. They move either their hands or heads slightly, trying to ignore the grim reaper, stating they are not ready for the afterlife.

Scandalous updates to the Prague clock

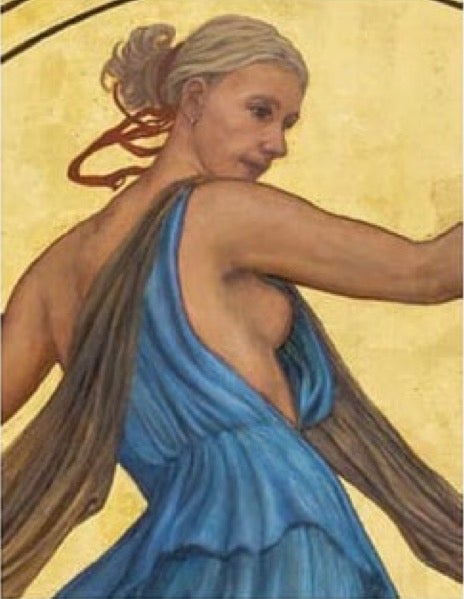

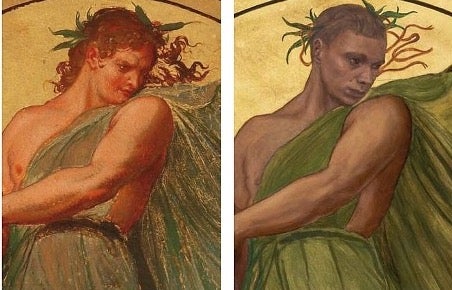

While the clock has been repaired many times over the years and all the moving components have been restored, nearly 75% are still original parts from the 15th century. But sometimes repairs and renovations bring shocking changes: In 2018, the calendar dial was reproduced by artist Stanislav Jirčík, following the original Josef Mánes paintings. However, the heritage group Club for Old Prague noticed some of the zodiac calendar paintings significantly changed, registering a complaint with the Czech culture ministry in 2022 and creating a scandal.

The artist was accused of “putting likenesses of friends and acquaintances on 15th-century clock, possibly as a joke” and “radically (changing) the appearance, ages, skin tone, dress and even genders of the figures.”

The controversy raised questions regarding the artist’s intentions, as well as how well conservationists and Prague City Hall checked his work, since it took four years before the concerns were raised. As of 2022, officials were discussing if a new calendar wheel that more faithfully re-creates the original artwork would be needed.

Renovation scandals aside, clock is a fascinating landmark from an artistic, engineering, and astronomical perspective. The tower also offers beautiful views of Prague, standing at 230 feet (70 meters). So if you have a few hours to spare in Prague, the tour of the Old Town Hall Tower and the Orloj is worth the – carefully measured – time.