In 2008, observations of the star WASP-12 detected a periodic dip in light as a large planet — cataloged as WASP-12b — passed in front of its host star. Planet hunting with transit instruments like SuperWASP allows astronomers to obtain a wealth of information about exoplanetary systems including their composition and size.

WASP-12b turns out to be one of the largest exoplanets found to date, and it completes each orbit around its parent star in just 26 hours. The planet is more than 155,000 miles (250,000 kilometers) across. With its atmosphere swollen by the intense heat it receives from the star, it makes it a “hot Jupiter.”

Hot Jupiters are similar to the planet Jupiter in our own solar system but located far closer to their host star — WASP-12b is 2.1 million miles (3.4 million km) away from WASP-12, which compares with the Earth-Sun distance of 93 million miles (150 million km). With such a small distance between them, violent interactions between the star and the planet can take place.

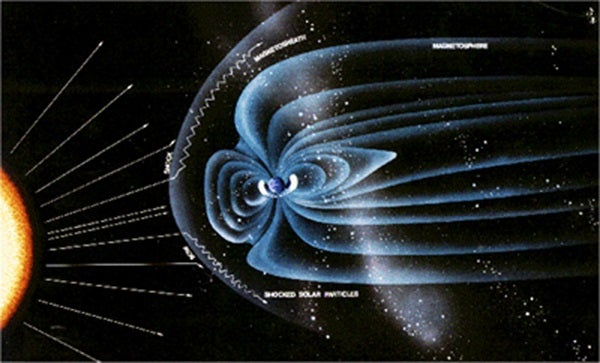

As one of the largest hot Jupiters discovered to date, WASP-12b also gives a unique opportunity to observe the interactions between the planetary magnetic field and the host star’s magnetic field. The very presence of a magnetic field reveals that the planet must have a conducting, rotating interior.

There is now tantalizing new evidence from Hubble Space Telescope data that a magnetosphere exists around WASP-12b. Observations of the planet taken in ultraviolet wavelengths by a team, including scientists from the Open University, reveal that the start of the dip in the light from the star during the transit of the planet is earlier in ultraviolet than visible light. Originally, material flowing from the planet onto the star was thought to have caused it. A University of St. Andrews, Scotland, group have, however, determined that the planet plows into a supersonic headwind and pushes a shock ahead of it — just like the one around a supersonic jet aircraft.

“The location of this bow shock provides us with an exciting new tool to measure the strength of planetary magnetic fields,” said Aline Vidotto from St. Andrews. “This is something that presently cannot be done in any other way.”

“Our models are able to reproduce the data from the Hubble Space Telescope for a range of wind speeds, implying that bow shocks could be far more commonplace than had been thought,” said Joe Llama from St. Andrews.

Bow shocks may also protect the atmospheres of hot Jupiters from their harsh environment. These planets are constantly bombarded with highly charged, energized particles from the wind from their parent stars, meaning that their atmosphere can be eroded. The presence of a magnetic field could greatly reduce the amount of stellar wind the planet is exposed to, effectively acting as a shield and helping the atmosphere survive.

“Although our model predicts a bow shock similar to that of the Earth, we are not expecting any messages from WASP-12b as it is too hot to support life,” said Joe Llama. “But the first hints that extrasolar planets have magnetosphere is a big step forward in understanding and identifying the habitable zones where we ultimately hope to find signs of life”.