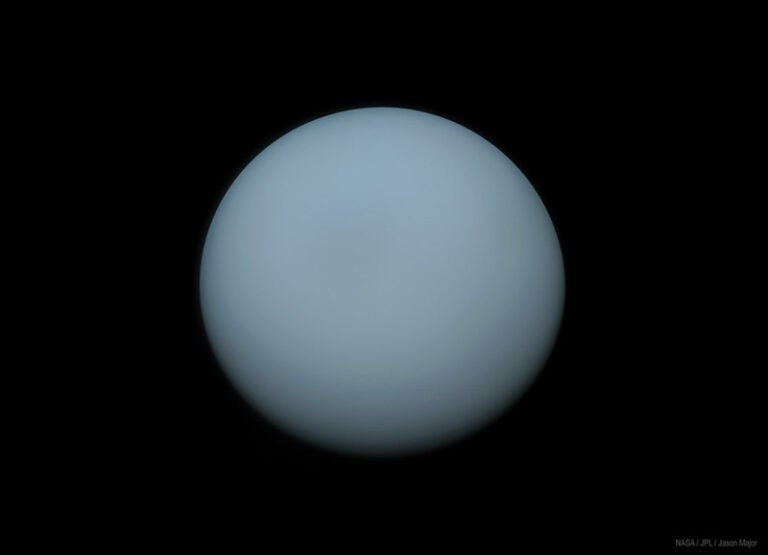

Uranus reached opposition and peak visibility near the end of October, and it remains a tempting target all this week. The outer planet appears in the eastern sky after darkness falls and climbs highest in the south around 10:30 p.m. local time. The magnitude 5.7 world lies in the southwestern corner of Aries, just over the border from Pisces, some 2.1° northeast of 4th-magnitude Omicron () Piscium. Although Uranus shines brightly enough to glimpse with the naked eye under a dark sky, use binoculars to locate it initially. Don’t confuse the planet with the magnitude 5.9 star SAO 92659. This evening, Uranus passes 14′ due south of this star. The easiest way to tell the two apart is to point a telescope at them. Only Uranus shows a disk, which spans 3.7″ and has a distinct blue-green hue.

Look for a two-day-old waxing Moon low in the southwest 30 to 45 minutes after sunset. Although the slim crescent appears only 6 percent lit, its unlit portion should show the faint illumination of earthshine. If you turn binoculars toward the Moon and lower them toward the horizon, you’ll also see Mercury 7° directly below it. Under excellent skies, you also might spot the fainter glow of the 1st-magnitude star Antares 2° to the planet’s lower left.

Saturday, November 10

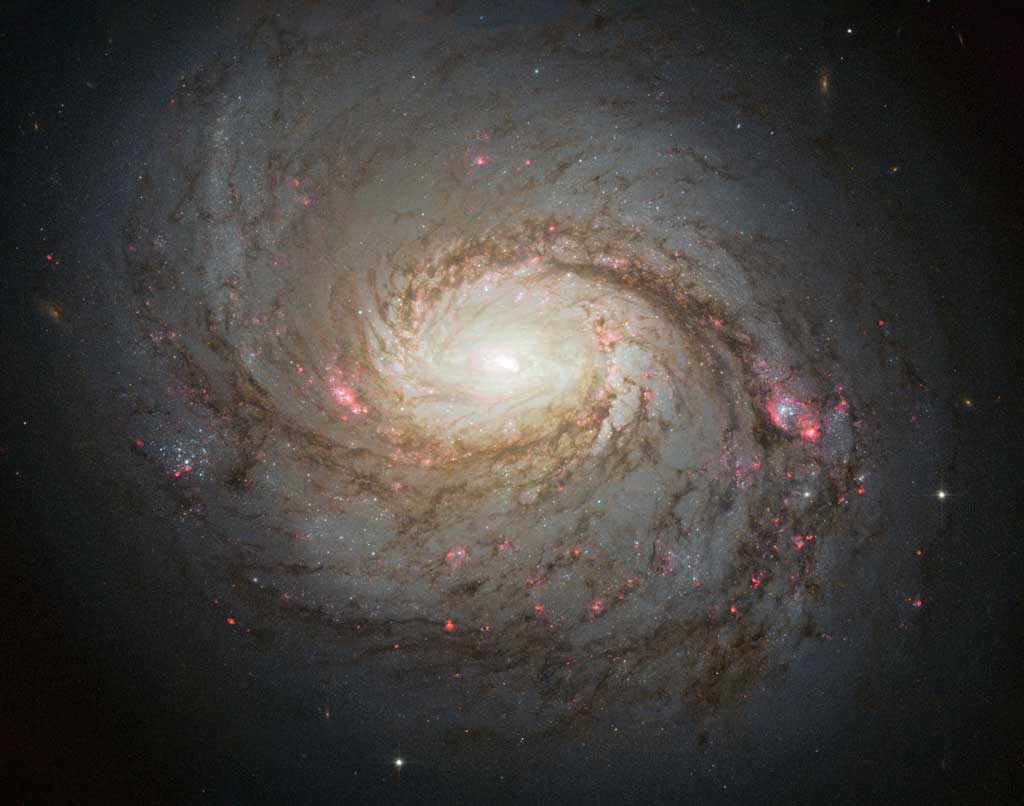

With the Moon out of the night sky, it’s a perfect time to explore some deep-sky objects. One of autumn’s finest galaxies lies just 0.9° east-southeast of the 4th-magnitude star Delta () Ceti. You can spot 9th-magnitude M77 through any telescope. At first glance, the barred spiral galaxy’s brilliant core will draw your attention. It appears conspicuous because gas is spiraling toward a supermassive black hole lurking in the galaxy’s heart. As this material settles into a disk, friction heats it to millions of degrees and causes it to shine brightly. You’ll likely need a 10-inch or larger scope to see M77’s spiral arms. To find more objects worth exploring these autumn nights, see “November’s 50 finest deep-sky objects” in the November issue of Astronomy.

The waxing crescent Moon appears 4° to Saturn’s upper left this evening. The two stand nearly 20° above the southwestern horizon an hour after sunset and will make a pretty pair with the naked eye and through binoculars. Of course, Saturn makes a tempting target any night this week. The ringed world shines at magnitude 0.6, more than a full magnitude brighter than any of the background stars in its host constellation, Sagittarius. The best views come through a telescope, however, which reveals a 16″-diameter globe surrounded by a spectacular ring system that spans 35″ and tilts 26° to our line of sight.

Monday, November 12

The variable star Algol in Perseus reaches minimum brightness at 8:10 p.m. EST, when it shines at magnitude 3.4. If you start watching it after darkness falls this evening, you can see it more than triple in brightness, to magnitude 2.1, over the course of several hours. This eclipsing binary star runs through a cycle from minimum to maximum and back every 2.87 days. Algol appears in the northeastern sky after sunset and passes nearly overhead around midnight local time.

Tuesday, November 13

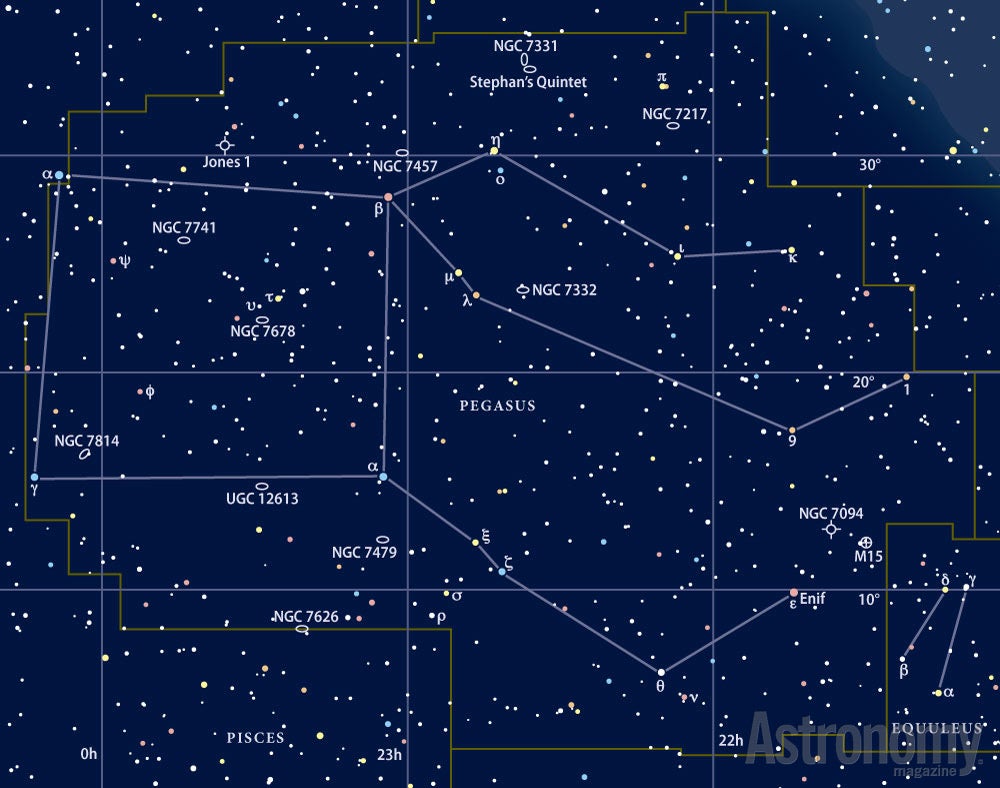

Look high in the southeast shortly after darkness falls this week, and you should see autumn’s most conspicuous star group. The Great Square of Pegasus stands out at this time of year, though in the early evening it is balanced on one corner and appears diamond-shaped. It looks more like a square when it climbs highest in the south around 8 p.m. local time. These four almost equally bright stars form the body of Pegasus the Winged Horse. The fainter stars that represent the rest of this constellation’s shape trail off to the square’s west.

Comet 64P/Swift-Gehrels currently glows between 9th and 10th magnitude and shows up nicely through 4-inch and larger telescopes. The comet should be particularly easy to find this evening because it appears less than 1° north of the 2nd-magnitude star Mirach (Beta [β] Andromedae). This region passes nearly overhead for observers at mid-northern latitudes between 9 and 10 p.m. local time. While you’re exploring this area, also look for the 10th-magnitude elliptical galaxy NGC 404, which lies a mere 7′ northwest of Mirach. Swift-Gehrels should appear more conspicuous than the galaxy.

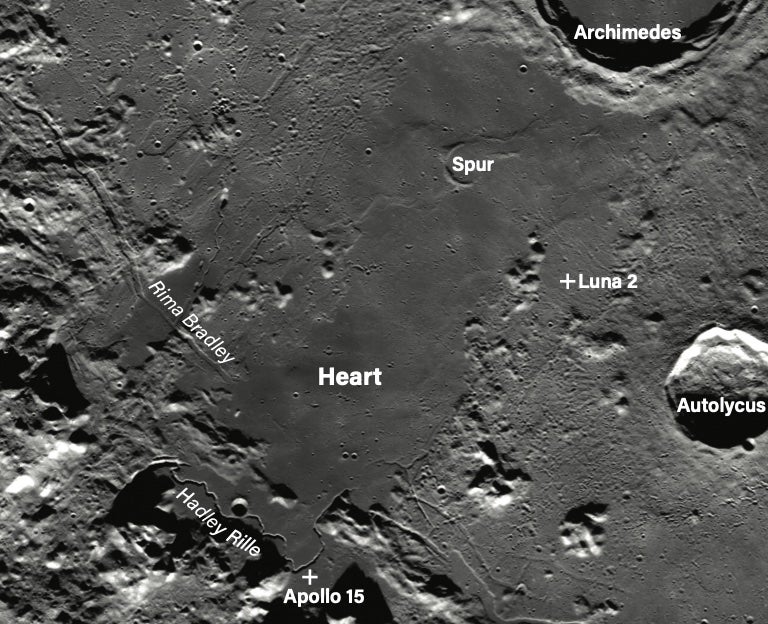

The Moon reaches apogee, the farthest point in its orbit around Earth, at 10:56 a.m. EST. It then lies 251,245 miles (404,339 kilometers) from Earth’s center.

Thursday, November 15

First Quarter Moon occurs at 9:54 a.m. EST. Once darkness settles over the Northern Hemisphere this evening, the half-lit Moon stands due south and nearly halfway from the horizon to the zenith. As you look toward the Moon, you can’t help but notice a bright orange object just above it. This is Mars, which currently shines at magnitude –0.3. Our satellite slides 1.0° (two Moon-widths) due south of the Red Planet at 11 p.m. EST. Although Mars looks impressive this evening, it stands out even more against the faint background stars of Aquarius the Water-bearer when the Moon isn’t nearby. Use a telescope to observe subtle surface markings on the planet’s 10.5″-diameter disk.

Friday, November 16

Asteroid 3 Juno puts on a grand performance this week. Although it reaches opposition tomorrow evening, it appears just as bright tonight. Glowing at magnitude 7.4 — easy to spot with binoculars under a reasonably dark sky and a cinch to locate through a telescope — it appears brighter than it has since October 1983. You can find Juno floating among the relatively faint background stars of northern Eridanus the River. This evening, it lies 0.4° south-southwest of the magnitude 4.7 star 32 Eridani.

Saturday, November 17

The annual Leonid meteor shower peaks tonight. With the waxing gibbous Moon setting before 2 a.m. local time and morning twilight beginning after 5 a.m., skywatchers have more than three hours for undisturbed viewing. The meteors radiate from the constellation Leo the Lion, which climbs more than 60° high in the southeast before dawn. Observers under a dark sky could see an average of between 15 and 20 meteors per hour. Leonid meteors come from tiny dust particles ejected by periodic comet 55P/Tempel-Tuttle during its innumerable passes through the inner solar system. When these bits of debris slam into Earth’s atmosphere at 44 miles per second, friction with air molecules incinerates them and produces the bright streaks.

If you are out before dawn viewing the Leonid meteor shower, you’ll be equally dazzled by Venus. The inner planet passed between the Sun and Earth just three weeks ago, but its rapid orbital motion has already brought it back to prominence. This morning, the planet rises 2.5 hours before the Sun and climbs 10° high in the east-southeast by the time morning twilight begins. Shining at magnitude –4.8, the brilliant world remains conspicuous even in bright twilight. Look carefully and you’ll also see 1st-magnitude Spica, Virgo the Maiden’s brightest star, less than 2° to the planet’s upper right. When viewed through a telescope, Venus displays a 50″-diameter disk that is just 14 percent lit.