As a space artist, I have had the thrill of participating in scientific discovery, often being the first artist to imagine what new objects might look like. Space artists usually work to the scientist’s directive, although sometimes they get it first. In the 1920s, Lucian Rudaux showed pinkish skies on Mars decades before Viking revealed them to us.

But I had not experienced that thrill of discovery itself — until recently.

Surrounded by spikes

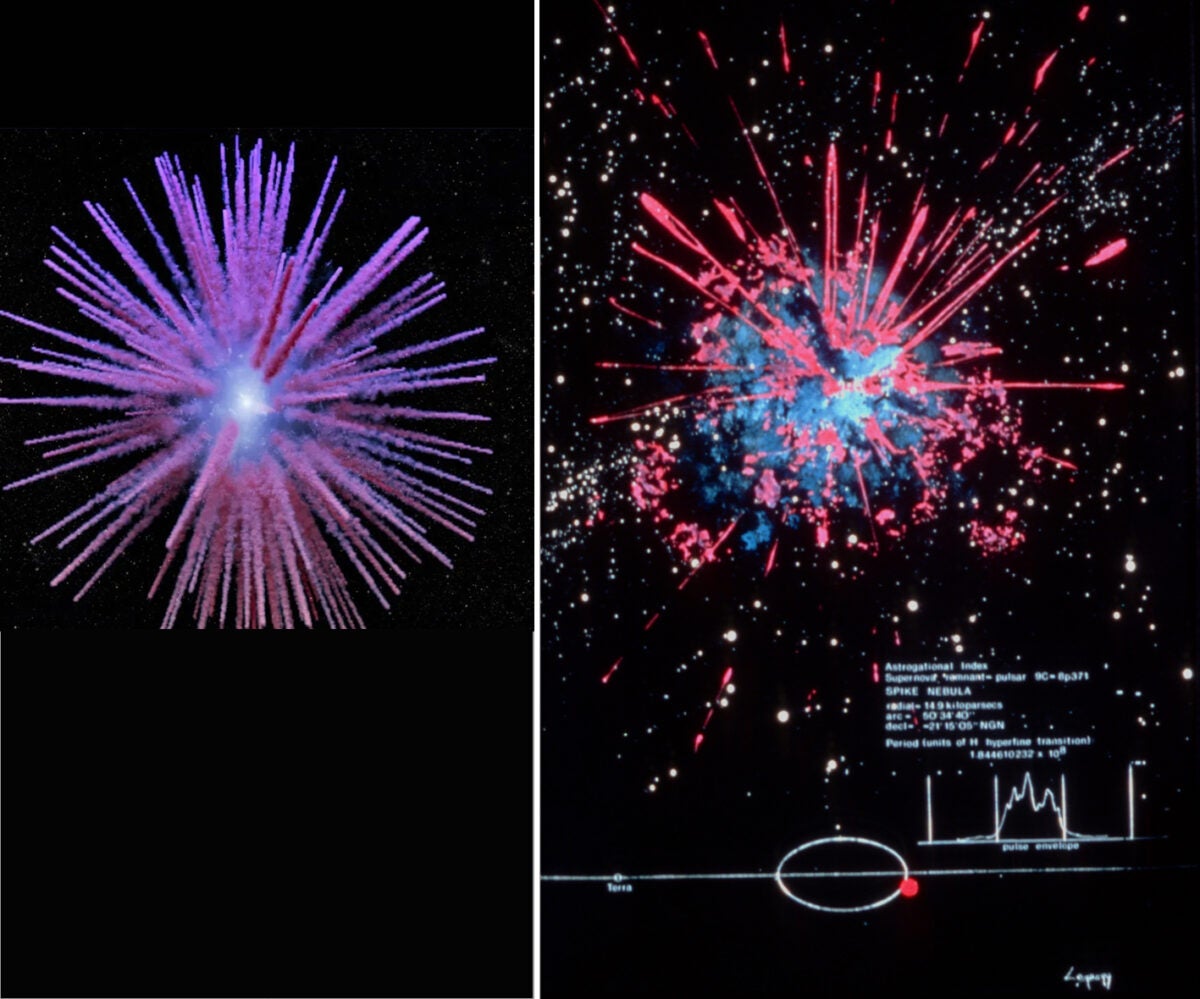

In 2024, Tim Cunningham at the Harvard Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics studied an unusual supernova remnant called SN 1181. It has a striking structure quite unlike any previously seen. Eight hundred years ago, astronomers in China and Japan recorded the supernova blazing in the night sky, and the remnant itself was discovered in 2013. Using the Keck Observatory in Hawaii, Cunningham and colleagues studied the debris from the explosion. They were able to make a model that revealed a unique network of spikes stretching up to 3 light-years from the original star, which was probably a white dwarf that blew up in what is called a type Ia supernova. What’s left is a structure of spiky filaments.

Nothing like it has been observed before.

But amazingly, I seem to have painted a similar object in 1975. I was then collaborating with Carl Sagan on several projects and spent a lot of time at Cornell University, where he was a professor. There I also met Frank Drake and Yervent Terzian, and had stimulating conversations with both of them. Terzian gave me a copy of his Optical Atlas of Galactic Supernova Remnants and explained his ideas on the morphology of these objects. Drake introduced me to some of the mysteries of pulsars, which at that time were still a fairly recent discovery. My work benefitted and was inspired by both of these astronomers.

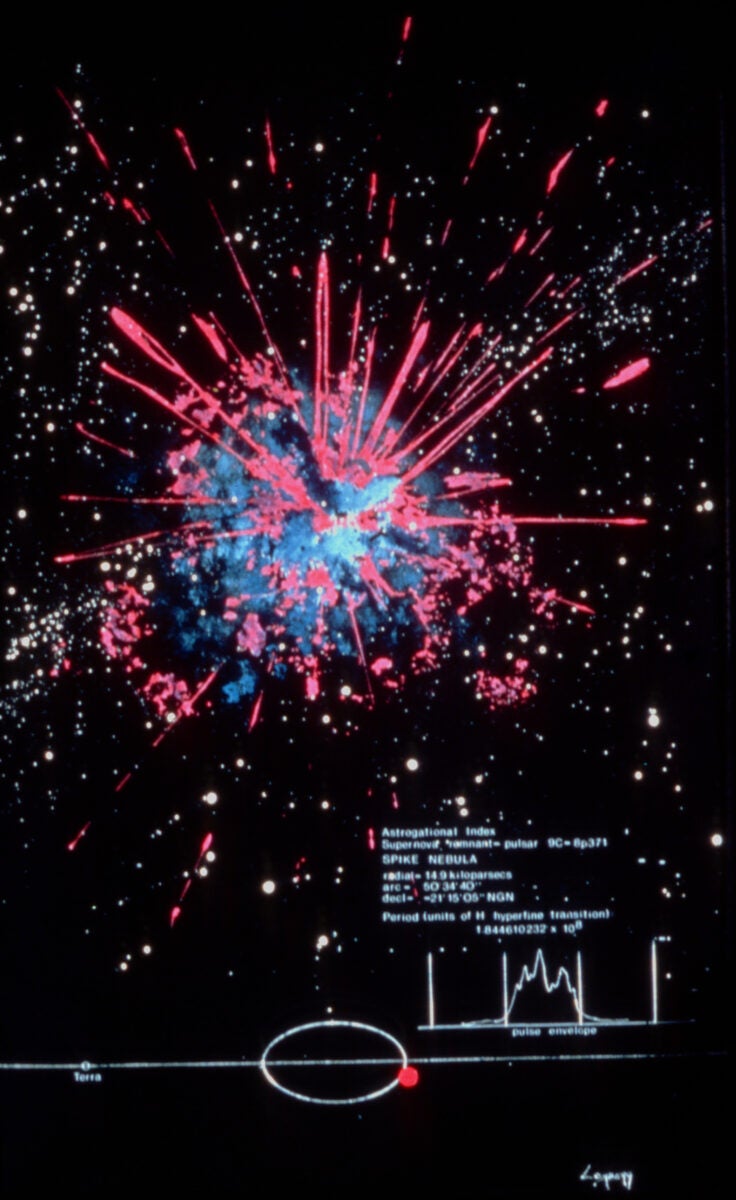

At the same time, I was working on a series of paintings based on Carl’s notion of an Encyclopedia Galactica (EG), a shared information repository among galactic civilizations. Frank commented that pulsars — natural beacons for astrogation — would certainly be included.

So I set out to do a painting of how such an object might appear in the EG. I was to work closely with both Frank and Carl a few years later on designing the Voyager Golden Record, which in fact contains just the sort of pulsar map we were discussing. Frank helped me with the details so I knew how to characterize the emission from the pulsar.

The first thing was to picture the supernova remnant surrounding the pulsar. I studied Terzian’s Atlas and decided to envision a recent supernova. I wondered what would happen if the exploding star were surrounded by a thick shell of gas and debris. (Since then, dusty disks have in fact been detected around white dwarfs.) I thought that maybe the explosion would break through the thinnest areas of the shell first, sending jets of material out through the holes and forming spikes. It also made the image look satisfyingly explosive. The text on the painting, supposedly the “printout” from the EG, reads as follows:

ASTROGATIONAL INDEX

SUPERNOVA REMNANT 9C-8P371

SPIKE NEBULA

The entry goes on to give its galactic location according to some alien system. The “9C” was an inside joke, referring to the 9th Cambridge Catalogue, a remote descendant of the 20th century’s 3rd Cambridge Catalogue (3C), which I also consulted at Frank’s suggestion. Carl liked the painting too.

When life mirrors art

Imagine my surprise 50 years later, when I saw the artist’s rendering of Cunningham’s data. Everything about the images matched up, except that no pulsar has been detected in this object.

When I showed him my painting, Cunningham wrote to me: “This is most interesting, in large part because the formation mechanism for the filaments in the SN 1181 remnant, has not be decisively established. Currently, the two contending theories are 1) a fast stellar wind producing cometary tails from clumps of dust, or 2) a reverse shock wave propagating from the outer edge of the nebula back toward the central star, sublimating dust, which then condenses into filaments.”

He went on to say: “I am curious to know what mechanism(s) you … envisioned in the creation of your animation … There is no denying that your animation bears a striking resemblance to the SN 1181 remnant.”

So, did I predict this object? In science you not only have to be right, you have to be right for the right reason. In 1912, Alfred Wegener proposed that the continents had drifted apart, somehow floating on the oceans, but he had no plausible mechanism to account for it. It wasn’t until 50 years later that plate tectonics revealed that mechanism. Wegener thought of it first, but for the wrong reason. Nevertheless he gets some credit for it.

The jury is still out on what causes the amazing spikes in SN 1181. Cunningham’s observational campaign continues, and he hopes soon to have a better reconstruction of the nebula using the Keck telescope. He has also proposed to study this remnant with the James Webb Space Telescope, and plans to propose for Hubble Space Telescope observations to gain exquisite images of this remarkable nebula.

I’ll be curious to see what further studies reveal, but as a space artist it is enormously gratifying to have imagined something close to what was found to exist.