“A widely accepted theory predicts that stars like this, with low mass and extremely low quantities of metals, shouldn’t exist because the clouds of material from which they formed could never have condensed,” said Elisabetta Caffau from University of Heidelberg, Germany, and the Observatory of Paris, France. “It was surprising to find, for the first time, a star in this ‘forbidden zone,’ and it means we may have to revisit some of the star formation models.”

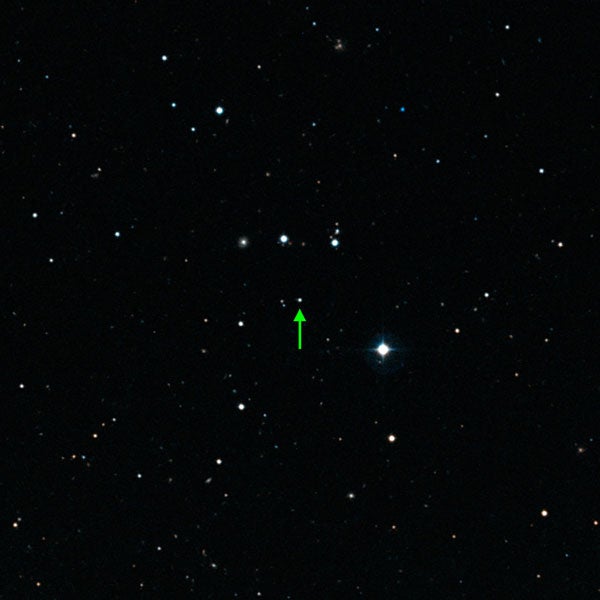

The team analyzed the properties of the star using the X-shooter and UVES instruments on the Very Large Telescope (VLT) in Atacama, Chile. This allowed them to measure how abundant the various chemical elements were in the star. They found that the proportion of metals in SDSS J102915+172927 is more than 20,000 times smaller than that of the Sun.

“The star is faint and so metal-poor that we could only detect the signature of one element heavier than helium — calcium — in our first observations,” said Piercarlo Bonifacio from the Observatory of Paris. “We had to ask for additional telescope time from The European Southern Observatory’s (ESO) director general to study the star’s light in even more detail, and with a long exposure time, to try to find other metals.”

Cosmologists believe that the lightest chemical elements — hydrogen and helium — were created shortly after the Big Bang, together with some lithium, while almost all other elements were formed later in stars. Supernova explosions spread the stellar material into the interstellar medium, making it rich in metals. New stars form from this enriched medium, so they have higher amounts of metals in their composition than the older stars; therefore, the proportion of metals in a star tells us how old it is.

“The star we have studied is extremely metal-poor, meaning it is very primitive,” said Lorenzo Monaco from ESO. “It could be one of the oldest stars ever found.”

Also very surprising was the lack of lithium in SDSS J102915+172927. Such an old star should have a composition similar to that of the universe shortly after the Big Bang, with a few more metals in it. But the team found that the proportion of lithium in the star was at least 50 times less than expected in the material produced by the Big Bang.

“It is a mystery how the lithium that formed just after the beginning of the universe was destroyed in this star,” Bonifacio added.

The researchers also point out that this freakish star is probably not unique. “We have identified several more candidate stars that might have metal levels similar to, or even lower than, those in SDSS J102915+172927. We are now planning to observe them with the VLT to see if this is the case,” said Caffau.

“A widely accepted theory predicts that stars like this, with low mass and extremely low quantities of metals, shouldn’t exist because the clouds of material from which they formed could never have condensed,” said Elisabetta Caffau from University of Heidelberg, Germany, and the Observatory of Paris, France. “It was surprising to find, for the first time, a star in this ‘forbidden zone,’ and it means we may have to revisit some of the star formation models.”

The team analyzed the properties of the star using the X-shooter and UVES instruments on the Very Large Telescope (VLT) in Atacama, Chile. This allowed them to measure how abundant the various chemical elements were in the star. They found that the proportion of metals in SDSS J102915+172927 is more than 20,000 times smaller than that of the Sun.

“The star is faint and so metal-poor that we could only detect the signature of one element heavier than helium — calcium — in our first observations,” said Piercarlo Bonifacio from the Observatory of Paris. “We had to ask for additional telescope time from The European Southern Observatory’s (ESO) director general to study the star’s light in even more detail, and with a long exposure time, to try to find other metals.”

Cosmologists believe that the lightest chemical elements — hydrogen and helium — were created shortly after the Big Bang, together with some lithium, while almost all other elements were formed later in stars. Supernova explosions spread the stellar material into the interstellar medium, making it rich in metals. New stars form from this enriched medium, so they have higher amounts of metals in their composition than the older stars; therefore, the proportion of metals in a star tells us how old it is.

“The star we have studied is extremely metal-poor, meaning it is very primitive,” said Lorenzo Monaco from ESO. “It could be one of the oldest stars ever found.”

Also very surprising was the lack of lithium in SDSS J102915+172927. Such an old star should have a composition similar to that of the universe shortly after the Big Bang, with a few more metals in it. But the team found that the proportion of lithium in the star was at least 50 times less than expected in the material produced by the Big Bang.

“It is a mystery how the lithium that formed just after the beginning of the universe was destroyed in this star,” Bonifacio added.

The researchers also point out that this freakish star is probably not unique. “We have identified several more candidate stars that might have metal levels similar to, or even lower than, those in SDSS J102915+172927. We are now planning to observe them with the VLT to see if this is the case,” said Caffau.