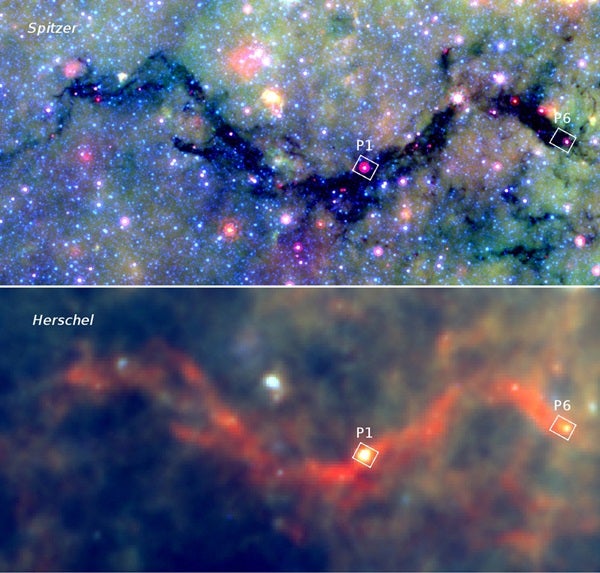

Stretching across almost 100 light-years of space, the Snake Nebula is located about 11,700 light-years from Earth in the direction of the constellation Ophiuchus. In images from NASA’s Spitzer Space Telescope, it appears as a sinuous dark tendril against the starry background. It was targeted because it shows the potential to form many massive stars (stars heavier than eight times our Sun).

“To learn how stars form, we have to catch them in their earliest phases, while they’re still deeply embedded in clouds of gas and dust, and the SMA is an excellent telescope to do so,” said Ke Wang of the European Southern Observatory (ESO).

The team studied two specific spots within the Snake Nebula, designated P1 and P6. Within those two regions, they detected a total of 23 cosmic “seeds” — faintly glowing spots that will eventually birth one or a few stars. The seeds generally weigh between five and 25 times the mass of the Sun, and each spans only a few thousand astronomical units — the average Earth-Sun distance. The sensitive high-resolution SMA images not only unveil the small seeds, but also differentiate them in age.

Previous theories proposed that high-mass stars form within massive isolated “cores” weighing at least 100 times the mass of the Sun. These new results show that that is not the case. The data also demonstrate that massive stars aren’t born alone but in groups.

“High-mass stars form in villages,” said Qizhou Zhang of the Center for Astrophysics in Cambridge, Massachusetts. “It’s a family affair.”

The team also was surprised to find that these two nebular patches had fragmented into individual star seeds so early in the star formation process.

They detected bipolar outflows and other signs of active, ongoing star formation. Eventually, the Snake Nebula will dissolve and shine as a chain of several star clusters.