“Bright X-ray novae are so rare that they’re essentially once-a-mission events, and this is the first one Swift has seen,” said Neil Gehrels from NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland. “This is really something we’ve been waiting for.”

An X-ray nova is a short-lived X-ray source that appears suddenly, reaches its emission peak in a few days, and then fades out over a period of months. The outburst arises when a torrent of stored gas suddenly rushes toward one of the most compact objects known, either a neutron star or a black hole.

The rapidly brightening source triggered Swift’s Burst Alert Telescope twice on the morning of September 16, and once again the next day.

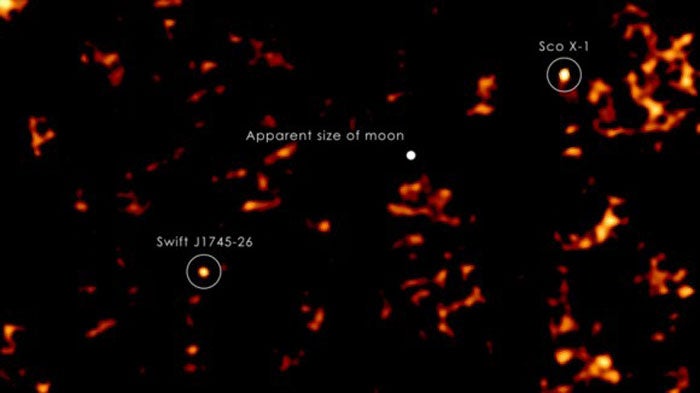

Named Swift J1745-26 after the coordinates of its sky position, the nova is located a few degrees from the center of our galaxy toward the constellation Sagittarius. While astronomers do not know its precise distance, they think the object resides about 20,000 to 30,000 light-years away in the galaxy’s inner region.

Ground-based observatories detected infrared and radio emissions, but thick clouds of obscuring dust have prevented astronomers from catching Swift J1745-26 in visible light.

The nova peaked in hard X-rays — energies above 10,000 electron volts, or several thousand times that of visible light — on September 18. It reached an intensity equivalent to that of the famous Crab Nebula, a supernova remnant that serves as a calibration target for high-energy observatories and is considered one of the brightest sources beyond the solar system at these energies.

Even as it dimmed at higher energies, the nova brightened in the lower-energy, or softer, emissions detected by Swift’s X-ray Telescope, a behavior typical of X-ray novae. By September 19, Swift J1745-26 was 30 times brighter in soft X-rays than when it was discovered, and it continued to brighten.

“The pattern we’re seeing is observed in X-ray novae where the central object is a black hole. Once the X-rays fade away, we hope to measure its mass and confirm its black hole status,” said Boris Sbarufatti from Brera Observatory in Milan, Italy, who currently is working with other Swift team members at Penn State in University Park.

The black hole must be a member of a low-mass X-ray binary (LMXB) system, which includes a normal Sun-like star. A stream of gas flows from the normal star and enters into a storage disk around the black hole. In most LMXBs, the gas in the disk spirals inward, heats up as it heads toward the black hole, and produces a steady stream of X-rays.

But under certain conditions, stable flow within the disk depends on the rate of matter flowing into it from the companion star. At certain rates, the disk fails to maintain a steady internal flow and instead flips between two dramatically different conditions — a cooler, less-ionized state where gas simply collects in the outer portion of the disk like water behind a dam, and a hotter, more-ionized state that sends a tidal wave of gas surging toward the center.

“Each outburst clears out the inner disk, and with little or no matter falling toward the black hole, the system ceases to be a bright source of X-rays,” said John Cannizzo from Goddard. “Decades later, after enough gas has accumulated in the outer disk, it switches again to its hot state and sends a deluge of gas toward the black hole, resulting in a new X-ray outburst.”

This phenomenon, called the thermal-viscous limit cycle, helps astronomers explain transient outbursts across a wide range of systems, from protoplanetary disks around young stars to dwarf novae — where the central object is a white dwarf star — and even bright emission from supermassive black holes in the hearts of distant galaxies.

“Bright X-ray novae are so rare that they’re essentially once-a-mission events, and this is the first one Swift has seen,” said Neil Gehrels from NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland. “This is really something we’ve been waiting for.”

An X-ray nova is a short-lived X-ray source that appears suddenly, reaches its emission peak in a few days, and then fades out over a period of months. The outburst arises when a torrent of stored gas suddenly rushes toward one of the most compact objects known, either a neutron star or a black hole.

The rapidly brightening source triggered Swift’s Burst Alert Telescope twice on the morning of September 16, and once again the next day.

Named Swift J1745-26 after the coordinates of its sky position, the nova is located a few degrees from the center of our galaxy toward the constellation Sagittarius. While astronomers do not know its precise distance, they think the object resides about 20,000 to 30,000 light-years away in the galaxy’s inner region.

Ground-based observatories detected infrared and radio emissions, but thick clouds of obscuring dust have prevented astronomers from catching Swift J1745-26 in visible light.

The nova peaked in hard X-rays — energies above 10,000 electron volts, or several thousand times that of visible light — on September 18. It reached an intensity equivalent to that of the famous Crab Nebula, a supernova remnant that serves as a calibration target for high-energy observatories and is considered one of the brightest sources beyond the solar system at these energies.

Even as it dimmed at higher energies, the nova brightened in the lower-energy, or softer, emissions detected by Swift’s X-ray Telescope, a behavior typical of X-ray novae. By September 19, Swift J1745-26 was 30 times brighter in soft X-rays than when it was discovered, and it continued to brighten.

“The pattern we’re seeing is observed in X-ray novae where the central object is a black hole. Once the X-rays fade away, we hope to measure its mass and confirm its black hole status,” said Boris Sbarufatti from Brera Observatory in Milan, Italy, who currently is working with other Swift team members at Penn State in University Park.

The black hole must be a member of a low-mass X-ray binary (LMXB) system, which includes a normal Sun-like star. A stream of gas flows from the normal star and enters into a storage disk around the black hole. In most LMXBs, the gas in the disk spirals inward, heats up as it heads toward the black hole, and produces a steady stream of X-rays.

But under certain conditions, stable flow within the disk depends on the rate of matter flowing into it from the companion star. At certain rates, the disk fails to maintain a steady internal flow and instead flips between two dramatically different conditions — a cooler, less-ionized state where gas simply collects in the outer portion of the disk like water behind a dam, and a hotter, more-ionized state that sends a tidal wave of gas surging toward the center.

“Each outburst clears out the inner disk, and with little or no matter falling toward the black hole, the system ceases to be a bright source of X-rays,” said John Cannizzo from Goddard. “Decades later, after enough gas has accumulated in the outer disk, it switches again to its hot state and sends a deluge of gas toward the black hole, resulting in a new X-ray outburst.”

This phenomenon, called the thermal-viscous limit cycle, helps astronomers explain transient outbursts across a wide range of systems, from protoplanetary disks around young stars to dwarf novae — where the central object is a white dwarf star — and even bright emission from supermassive black holes in the hearts of distant galaxies.