“The distance still separating Rosetta from 67P is now far from astronomical,” said OSIRIS Principal Investigator Holger Sierks from the Max Planck Institute for Solar System Research (MPS) in Germany. “It’s a trip of less than 12,000 kilometers [7,500 miles]. That’s comparable to traveling from Germany to Hawaii.”

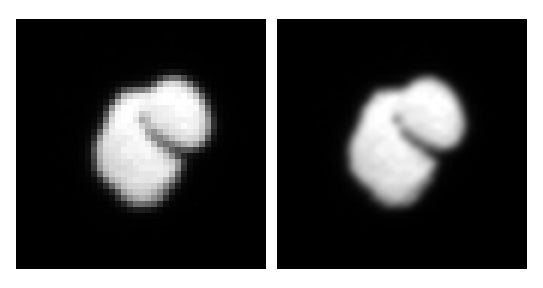

However, while taking a snapshot of Mauna Kea, Hawaii’s highest mountain, from Germany is an impossible feat, Rosetta’s camera OSIRIS is doing a great job at catching ever clearer glimpses of its similarly sized destination. Images obtained July 14 clearly show a tantalizing shape. The comet’s nucleus consists of two distinctly separate parts.

“This is unlike any other comet we have ever seen before,” said Carsten Güttler from MPS. “The images faintly remind me of a rubber ducky with a body and a head,” he added with a laugh.

How 67P received this duck-like shape is still unclear. “At this point, we know too little about 67P to allow for more than an educated guess,” said Sierks. In the next months, the scientists hope to determine more of the comet’s physical and mineralogical properties. These could help decide whether the comet’s body and head were formerly two individual bodies.

In order to get an idea of what seems to be a unique body, the observed image data can be interpolated to create a smoother shape. “There is, of course, still uncertainty in these processed filtered images, and the surface will not be as smooth as it now appears,” Güttler said. “But they help us to get a first idea.”