New observations from NASA’s Spitzer Space Telescope strongly suggest that infrared light detected in a prior study originated from clumps of the very first objects of the universe. The recent data indicate this patchy light is splattered across the entire sky and comes from clusters of bright, monstrous objects more than 13 billion light-years away.

“We are pushing our telescopes to the limit and are tantalizingly close to getting a clear picture of the very first collections of objects,” said Dr. Alexander Kashlinsky of NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center, Greenbelt, Md., lead author on two reports to appear in the Astrophysical Journal Letters. “Whatever these objects are, they are intrinsically incredibly bright and very different from anything in existence today.”

Astronomers believe the objects are either the first stars — humongous stars more than 1,000 times the mass of our sun — or voracious black holes that are consuming gas and spilling out tons of energy. If the objects are stars, then the observed clusters might be the first mini-galaxies containing a mass of less than about one million suns. The Milky Way galaxy holds the equivalent of approximately 100 billion suns and was probably created when mini-galaxies like these merged.

This study is a thorough follow-up to an initial observation presented in Nature in November 2005 by Kashlinksy and his team. The new analysis covered five sky regions and involved hundreds of hours of observation time.

Scientists say that space, time and matter originated 13.7 billion years ago in a tremendous explosion called the Big Bang. Observations of the cosmic microwave background by a co-author of the recent Spitzer studies, Dr. John Mather of Goddard, and his science team strongly support this theory. Mather is a co-winner of the 2006 Nobel Prize for Physics for this work. Another few hundred million years or so would pass before the first stars would form, ending the so-called dark age of the universe.

With Spitzer, Kashlinsky’s group studied the cosmic infrared background, a diffuse light from this early epoch when structure first emerged. Some of the light comes from stars or black hole activity so distant that, although it originated as ultraviolet and optical light, its wavelengths have been stretched to infrared wavelengths by the growing space-time that causes the universe’s expansion. Other parts of the cosmic infrared background are from distant starlight absorbed by dust and re-emitted as infrared light.

“There’s ongoing debate about what the first objects were and how galaxies formed,” said Dr. Harvey Moseley of Goddard, a co-author on the papers. “We are on the right track to figuring this out. We’ve now reached the hilltop and are looking down on the village below, trying to make sense of what’s going on.”

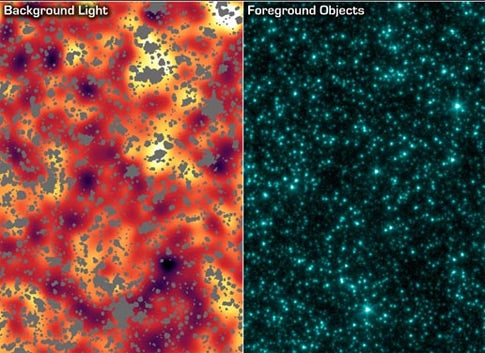

The analysis first involved carefully removing the light from all foreground stars and galaxies in the five regions of the sky, leaving only the most ancient light. The scientists then studied fluctuations in the intensity of infrared brightness, in the relatively diffuse light. The fluctuations revealed a clustering of objects that produced the observed light pattern.

“Imagine trying to see fireworks at night from across a crowded city,” said Kashlinsky. “If you could turn off the city lights, you might get a glimpse at the fireworks. We have shut down the lights of the universe to see the outlines of its first fireworks.”

Mather, who is senior project scientist for NASA’s future James Webb Space Telescope, said, “Spitzer has paved the way for the James Webb Space Telescope, which should be able to identify the nature of the clusters.”