Research published on August 20 in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences shows that specific signatures of water ice exist atop the cold, dark craters near the Moon’s poles — proving the existence of lunar surface ice for the first time.

This story probably sounds familiar, and that’s because it isn’t the first time we’ve found water particles on the Moon. Water was detected back in 2009 when NASA’s Lunar CRater Observation and Sensing Satellite (LCROSS) shot into the south pole’s Ceabeus crater and exposed its subsurface, but this only proved that water exists within the Moon, but not necessarily on the Moon’s surface. Other instruments have also detected reflective surfaces that resemble surface ice, but things like reflective soil could easily explain that away, rendering the findings inconclusive.

To finally get some hard evidence, a group of scientists looked back at data from NASA’s Moon Mineralogy Mapper (M3), a visible and infrared spectrometer that rode aboard India’s Chandrayaan-1 orbiter during its 2008-2009 tour. M3 was capable of directly measuring how molecules on the Moon’s surface absorb infrared light, which distinguishes surface ice from liquid water, water that’s held in minerals and water that’s hidden under the surface. It was also able to detect the specific reflective properties that are often given off by surface ice.

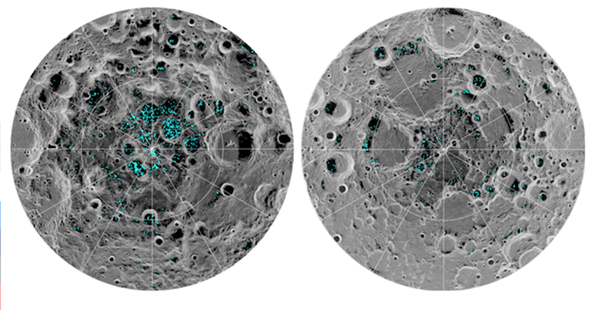

When they combined these two factors, they found reflective properties, as well as definitive interactions between molecules and infrared light, that indicate the presence of water ice on the lunar surface. The Moon’s south pole showed high concentrations of ice in lunar craters, whereas the north pole’s ice was more spread out across the surface.

Why ice was found congregating near the poles and in craters isn’t a complete mystery, either. Deep, frigid craters are often referred to as “cold traps” — areas so cold that water vapor inside them freezes and is unable to escape for significant periods of time, possibly billions of years. And due to the Moon’s tilt and rotation, the cold traps near the poles are shielded from direct sunlight and only reach -250 degrees Fahrenheit (-121 degrees Celsius). Compared to the maximum equatorial temperatures of 260 degrees Fahrenheit (126 degrees Celsius), the cold, polar basins are more likely to hold on to water.

And this is good news for astronauts. The surface ice might be easier to access than underground water, which could be useful in future manned missions. The amount of surface ice is unknown, but if there’s enough, missions could potentially use it as drinking water, convert it to oxygen for breathing, or use it as rocket fuel by converting it to oxygen and hydrogen.

There’s still a lot we don’t know about the newfound surface ice, but further exploration could help us understand how it got there, and what its role was in the Moon’s mysterious formation and evolution.