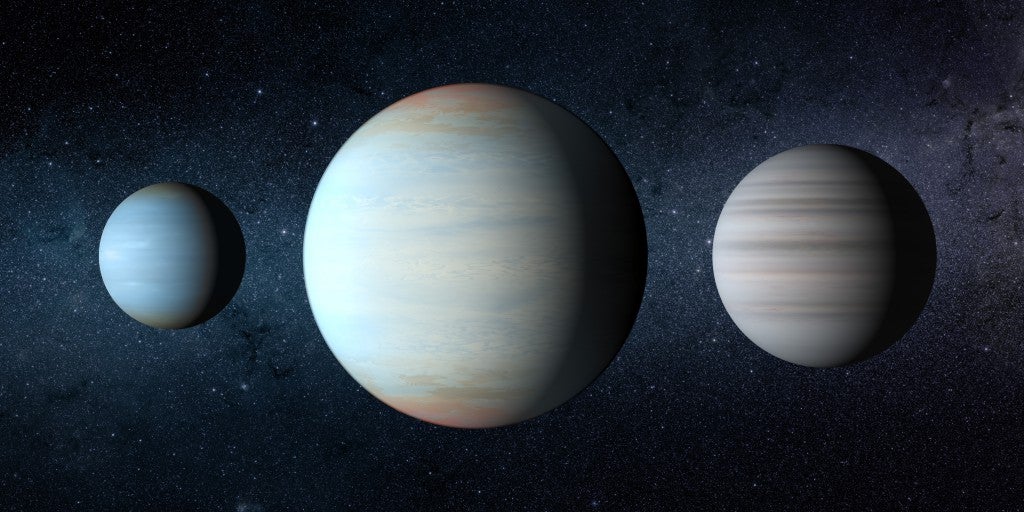

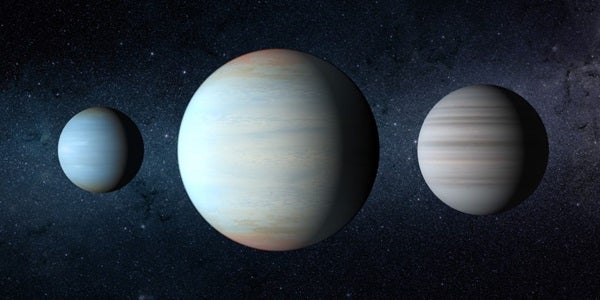

The three planets in the Kepler 47 system are illustrated here with the newest, largest planet in the middle.

NASA/JPL-Caltech/T. Pyle

Like the planet Tatooine from Star Wars, two suns — one bright, one dim and red— rise over the horizon of Kepler 47d. But unlike dry and sandy Tatooine, this planet’s surface is gassy and indistinct. The system also holds two smaller planets; one planet closer to the double suns, and one farther out. Both lack a solid surface. If you visited in a spaceship, all the planets would be easy to spot because they’re packed, along with their stars, into a space smaller than Earth’s orbit around the Sun. This week, astronomers on Earth announced that they’d only just now discovered the middle planet, making an already noteworthy system even more unique.

In fact, Kepler 47 is the only known multi-planet system orbiting a binary star. And it just solidified that place of honor by revealing a third planet hiding between the two already known planets. This tightly packed system has little in common with our solar system, and astronomers are therefore eager to learn all they can from it.

New planet creeps into view

Astronomers first spotted Kepler 47d back in 2012 using NASA’s Kepler space telescope, but the data were inconclusive. Observing a transit – when a planet passes in front of its star, causing a dip in light – requires a fair amount of luck. The planets must be perfectly aligned with their star and an Earth observer. And this one’s not quite perfect.

“The orbital planes are pretty closely aligned but not exactly,” Jerome Orosz, the lead author of the planet’s discovery paper, tells Astronomy. “There’s a few degrees of tilt. The angle of the orbital planes is changing with time over hundreds of years.” The first time Kepler 47d crossed its star in the data it did so just barely, enough to make astronomers suspicious, but not enough to be conclusive. But as the Kepler mission continued, the orbits came more into alignment until the signal from the middle planet was unmistakable. Orosz and his team published their findings Tuesday in the Astronomical Journal.

This change in the planet’s orbit wouldn’t affect its seasons – the Earth is also constantly precessing in the same way over long periods, with relatively little impact to the planet or the life on it.

That said, the seasons and temperature ranges on all three of these weird planets are a challenging and intriguing puzzle. Astronomers have no way of knowing at this point whether the planets tilt, as Earth does, which gives us most of our seasonal changes. But as the planets and stars orbit, the amount of energy reaching each planet would change drastically, especially as each world got close to the brighter of the two stars. “Your seasonal calendars get pretty complicated,” Orosz notes. Despite these changes, the outer planet seems to reside continuously in the habitable zone of the system. And while Kepler 47c is likely a gaseous planet with no solid surface, it may have moons that could host life.

To make things even more complicated, astronomers don’t think any of the planets could have formed on their current orbits. Instead,

each would have formed farther away from their stars and then migrated in. And migration is hard on moons, as it’s easy for them to get stripped away or left behind. Planets orbiting near their stars also have a harder time holding onto their moons. “If you magically move Saturn to where Venus is, lots of the longer period satellites wouldn’t be stable,” Orosz notes. And there’s not much spare room in the Kepler 47 system to begin with.

Putting the system together

The two stars in the system – one Sun-like, one smaller and cooler – orbit each other every seven-and-a-half days. Next out is Keper 47b, which orbits every 49 days and is about three times the size of Earth. The new planet, Kepler 47d, orbits every 187 days and is 7 times the size of Earth, while the last planet, Kepler 47c, has a 303-day orbit and is 4.7 times Earth’s size.

The planets’ masses are trickier to pin down, since Kepler only saw transits, which simply reveals how broad a planet is. But because the two stars and three planets all tug on each other, scientists have some idea about their masses, and they’re all surprisingly light for their sizes. The middle planet is roughly the density of Saturn – already famously light enough to float in a bathtub – while the outermost planet is less than half that dense. “Density is important, but by itself not necessarily helpful,” Orosz says. “If it’s a Saturn mass and density, then it’s a gas giant. But if it’s Earth mass and Saturn density, that’s very different.” That would mean these planets are unlike anything in our solar system, and scientists are always excited to find something new.

It’s still possible there are more planets lurking in the Kepler 47 system, though they’d have to be hiding farther out from the stars, which decreases the likelihood of them transiting and revealing themselves.

And while Kepler 47 remains the only multi-planet system around a binary star, that may be a trick of perception. Orosz said he wouldn’t be surprised if many of the circumbinary systems astronomers know about host other planets. Finding them will be a challenge, since most of them won’t transit. But as more observatories come online and study more systems, it’s almost guaranteed that astronomers will find more systems like Kepler 47.

Editor’s Note: An earlier version of this story incorrectly listed the orbital period of Keper 47d. The planet orbits its host stars in 187 days.