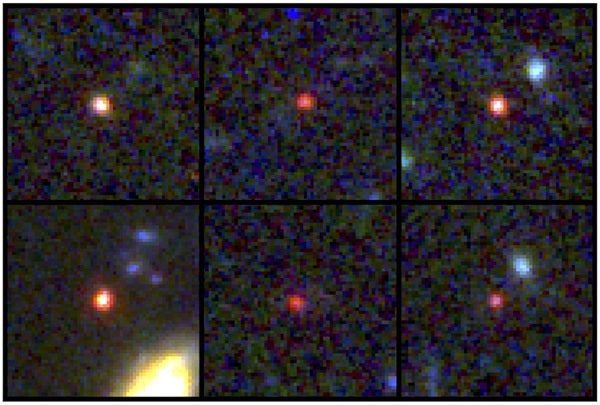

When the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) first delivered unprecedented images of some of the universe’s earliest galaxies, it left astronomers scratching their heads.

These distant galaxies, which formed within only a few hundred million years of the Big Bang, seemed too bright, too big, and too evolved for their age. And if that were the case, it would indicate the standard model of cosmology may have some significant issues.

However, new research, published in The Astrophysical Journal Letters, suggests a phenomenon called “bursty star formation” can explain this celestial puzzle – all without upending our current understanding of the universe.

“The key is to reproduce a sufficient amount of light in a system within a short amount of time,” said Guochao Sun, a Postdoctoral Fellow at Northwestern who led the study, in a press release. “If star formation happens in bursts, it will emit flashes of light. That is why we see several very bright galaxies.”

Shedding light on the universe’s first galaxies

The young galaxies captured in stunning detail by JWST challenged established astrophysical concepts. That’s because they appeared only shortly after the Big Bang yet possessed a luminosity that implied a mass and maturity far beyond their years. That’s because according to the standard model of cosmology, galaxies should start off quite small and grow through repeated galaxy mergers over a long period of time.

“The discovery of these galaxies was a big surprise because they were substantially brighter than anticipated,” said Claude-André Faucher-Giguère, an astronomer at Northwestern and co-author of the new study. “Typically, a galaxy is bright because it’s big. But because these galaxies formed at cosmic dawn, not enough time has passed since the Big Bang. How could these massive galaxies assemble so quickly?”

To probe this apparent problem, the researchers utilized advanced computer simulations carried out as part of the Feedback of Relativistic Environments (FIRE) project. These FIRE simulations are built to accurately model galaxy formation and growth by taking into account how stellar feedback (energy, mass, momentum, etc.) contributes to galactic evolution.

According to the research, the new simulations showed that the early galaxies captured by JWST could indeed owe their surprising brightness to a process known as bursty star formation. And not only that, but the simulations also closely replicated both the overall brightness and abundance of the unexpectedly bright galaxies JWST observed.

Bursty star formation

Instead of the steady rate of star formation typically observed in more modern and massive galaxies like the Milky Way, bursty star formation features short, intense periods of stellar birth and death followed by longer, quieter phases.

“Bursty star formation is especially common in low-mass galaxies,” said Faucher-Giguère. And though research on the subject is still ongoing, he said that “what we think happens is that a burst of stars form, then a few million years later, those stars explode as supernovae. The gas gets kicked out and then falls back in to form new stars, driving the cycle of star formation.

“But when galaxies get massive enough, they have much stronger gravity,” he said. “When supernovae explode, they are not strong enough to eject gas from the system. The gravity holds the galaxy together and brings it into a steady state.”

According to the simulations, this flash-bulb approach of bursty star formation can lead to some early galaxies emitting so much light that it inflates their implied mass. And perhaps most importantly, if this explanation is confirmed, it would avoid any required revisions or adjustments to the standard model of cosmology.

JWST helps us revisit assumptions

As JWST continues its vigilant watch, each image, each spectrum of light, helps raise new questions about the cosmos. And it’s these unexpected questions that drive astronomers to seek out new answers and insights.

“The JWST brought us a lot of knowledge about cosmic dawn,” Sun said. “Prior to JWST, most of our knowledge about the early universe was speculation based on data from very few sources. With the huge increase in observing power, we can see physical details about the galaxies and use that solid observational evidence to study the physics to understand what’s happening.”