Targets for June 9–16, 2016

Naked eyes: Three Boötes double stars

Small telescope: Ruby Crucis

Large telescope: Spiral galaxy M94

In basketball, a player achieves a “triple-double” when he or she reaches 10 or more in three statistical categories. This week’s naked-eye object is a selection of three double stars in the constellation Boötes — my very own triple-double.

The three stars are Kappa (κ), Iota (ι), and Pi (π) Boötis. Kappa slightly outshines the other two. It shines at magnitude 4.5, some 45 percent brighter than each of the others, which glow at magnitude 4.9. Once you find each of the three stars without optical aid, point a small telescope their way to reveal the double nature of each.

Kappa divides into stars of magnitudes 4.6 and 6.6, and 13.4″ separates the pair. The components are blue-white and white, or blue and white, depending on how your eyes see color. You’ll find this nice pair 1.8° west of magnitude 4.0 Theta (θ) Boötis.

Iota Boötis is an easy split through any telescope, and it also lies near Theta Boötis. To find it, just look 1.5° west-southwest of Theta or 0.6° southeast of Kappa. The magnitude 4.9 primary is yellow-white, and the magnitude 7.5 secondary glows white. The separation is a wide 38″.

Finally, you’ll find Pi Boötis 6.5° east-southeast of brilliant Arcturus (Alpha [α] Boötis), the sky’s fourth-brightest star. Pi’s magnitude 4.9 primary is white (or blue-white), and the magnitude 5.8 secondary is yellow (or yellow-white). The stars of this pair sit closer than our other two doubles — 5.6″ — but that’s still an easy split through a 3-inch telescope.

The southern sky’s ruby

This week’s small-telescope target is one of the sky’s reddest stars. Amateur astronomers call it Ruby Crucis because of its color, but the star’s scientific designation is DY Crucis. It sits in the southern constellation Crux.

Ruby Crucis is incredibly easy to find if you can observe south of about latitude 25° north. First locate magnitude 1.3 Mimosa (Beta [β] Crucis). Train your telescope on that brilliant star, crank the magnification past 100x, and look just 2′ to its west.

The only aspect that makes this observation a bit tough is that you have to move Mimosa out of the field of view so you can see Ruby Crucis without all of the glare Mimosa creates.

Like most of the sky’s super-red stars, Ruby Crucis is a variable. Its magnitude ranges from 8.4 to 9.8. The nearer you can view it to its minimum brightness, the redder it will appear.

A tightly wrapped spiral

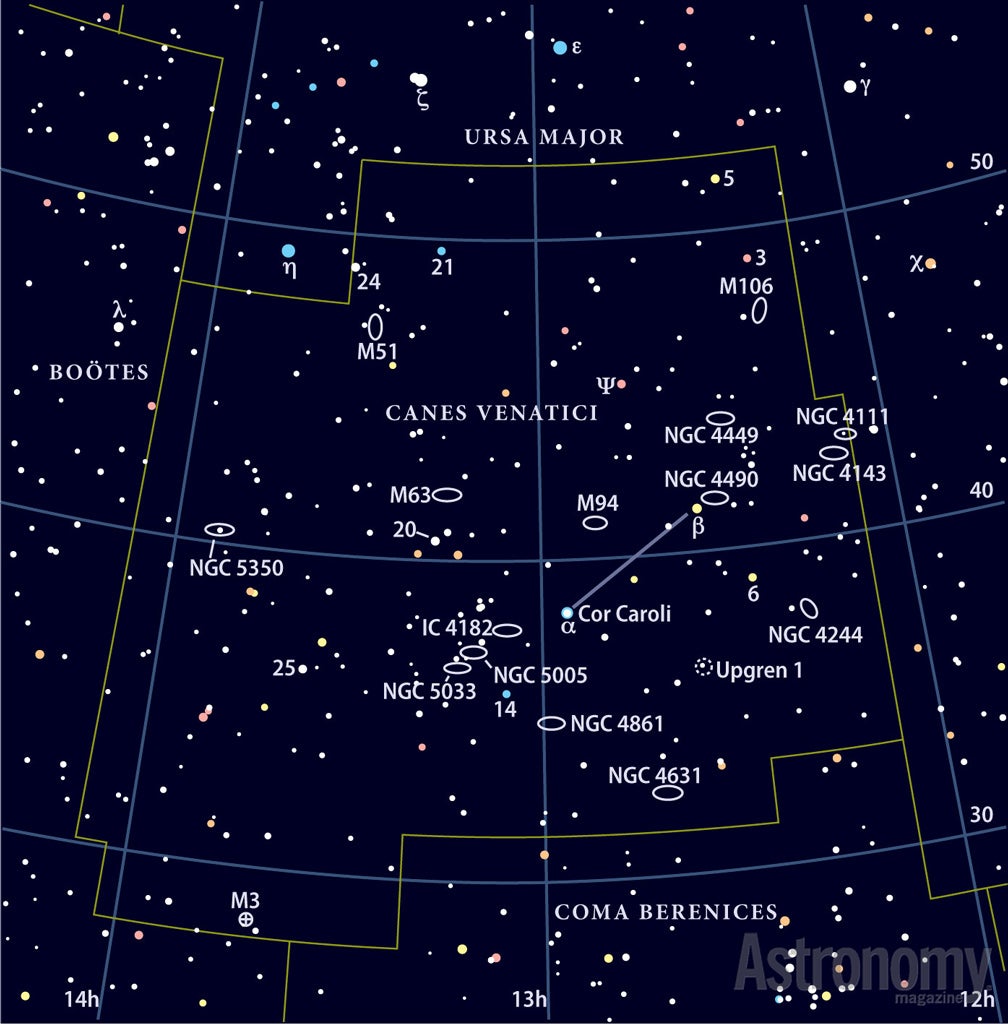

When does a face-on spiral galaxy not look like a spiral galaxy? When it’s this week’s large-telescope target: M94. This notable object is the brightest galaxy in the constellation Canes Venatici. It shines brightly (for a galaxy) at magnitude 8.2 and measures 13′ by 11′. Because of its tightly wrapped spiral arms, an observer using a small telescope might classify it as an elliptical galaxy. Look for it 3° north-northwest of magnitude 2.9 Cor Caroli (Alpha [α] Canum Venaticorum).

Pierre Méchain discovered M94 March 22, 1781. Messier observed M94, determined its position, and added it to his catalog just two days later. He called it a “nebula without star.”

British astronomer and author Admiral William H. Smyth (1788-1865) gave a more detailed description, but it certainly doesn’t describe a galaxy: “A comet-like nebula; a fine, pale-white object with evident symptoms of being a compressed cluster of small stars. It brightens toward the middle.”

Through an 11-inch telescope, you’ll see the galaxy’s tiny nucleus surrounded by a bright disk that measures only 30″ across. A much fainter oval halo surrounds the disk. Increase your telescope’s aperture to 16 inches, and you’ll begin to resolve the tightly wound spiral arms close to the nucleus.

Expand your observing at Astronomy.com

The Sky this Week

Get a daily digest of celestial events coming soon to a sky near you.

Observing Basics

Find more guidance from Senior Editor Michael E. Bakich with his Observing Basics video series.