As of 2025, astronomers have identified at least 14 stars within 10 light-years of the Sun. After the Alpha Centauri system, the next closest is Barnard’s Star, a solo red dwarf roughly 6 light-years away. And thanks to new observations, we now know that Barnard’s Star is orbited by four small, rocky exoplanets.

But it’s been a bumpy road. Since its discovery in 1916 by American astronomer Edward Emerson Barnard, Barnard’s star has seen several claims of orbiting worlds, dating back to the 1960s. Much more recently, a super-Earth was predicted in 2018, but this discovery was refuted in 2021.

Research published in August 2024 finally confirmed the presence of a planet orbiting Barnard’s Star, dubbed Barnard’s Star b or Barnard b for short.

And now, three additional planets have been confirmed in a paper published March 11 in The Astrophysical Journal Letters, bringing the count now to four planets.

Watching wobbles

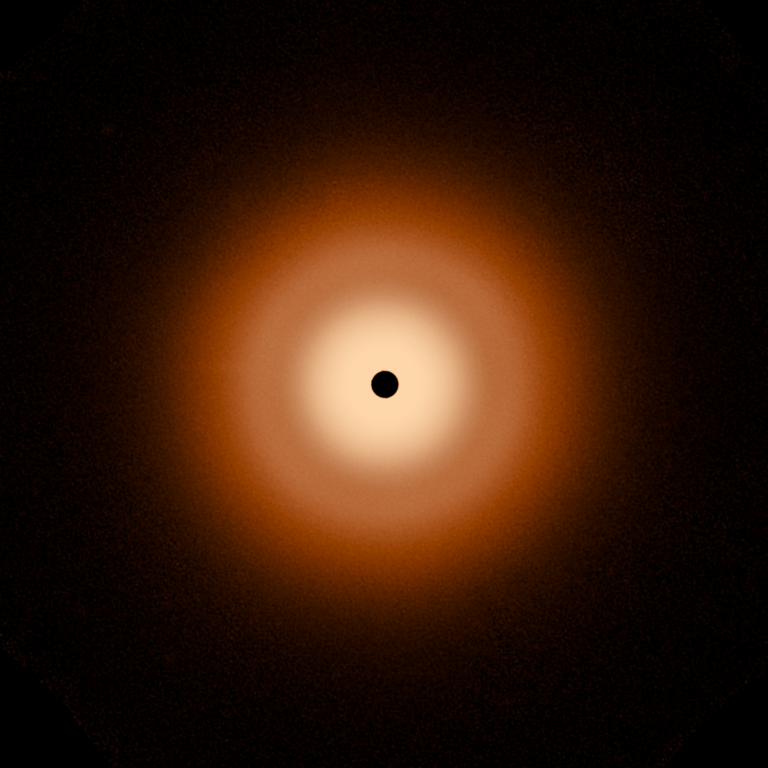

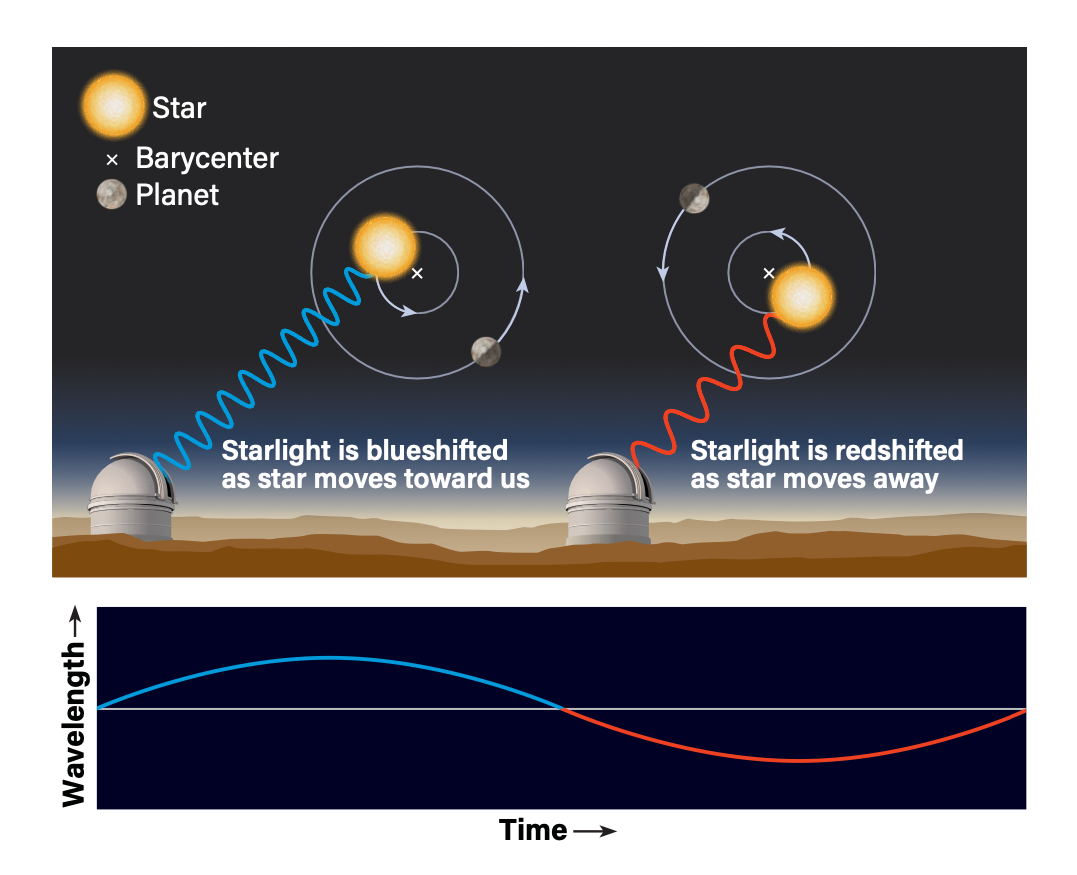

The planets were all found using the radial velocity or “wobble” method, which uses shifts in the wavelength of light from a star caused by the slight tug to and fro of an orbiting planet. Even tiny planets induce a slight wobble in their sun as the two orbit a shared center of gravity. By using instruments like ESPRESSO on the Very Large Telescope in Chile (which identified Barnard b) and MAROON-X on the Gemini North telescope in Hawaii (which found the recent three worlds), astronomers can detect the Doppler shift in light emitted from the star as it wobbles toward us and away again. The signature of this light also allows them to determine details about the planets in question, including their size.

The new research was led by a team from the University of Chicago that observed Barnard’s Star 112 times using MAROON-X between 2021 and 2023. They identified potential signals in their data during this time, but discounted them since MAROON-X was still being calibrated. This changed in late 2024, when a separate team identified Barnard’s Star b using ESPRESSO. This discovery prompted the UChicago team to revisit their data, leading to the discovery of Barnard’s Star c, d, and e.

The Barnard’s Star system

The previously discovered planet, Barnard b, is likely a rocky planet with roughly 30 percent Earth’s mass and an orbital period (or “year”) equal to approximately 3.15 Earth days.

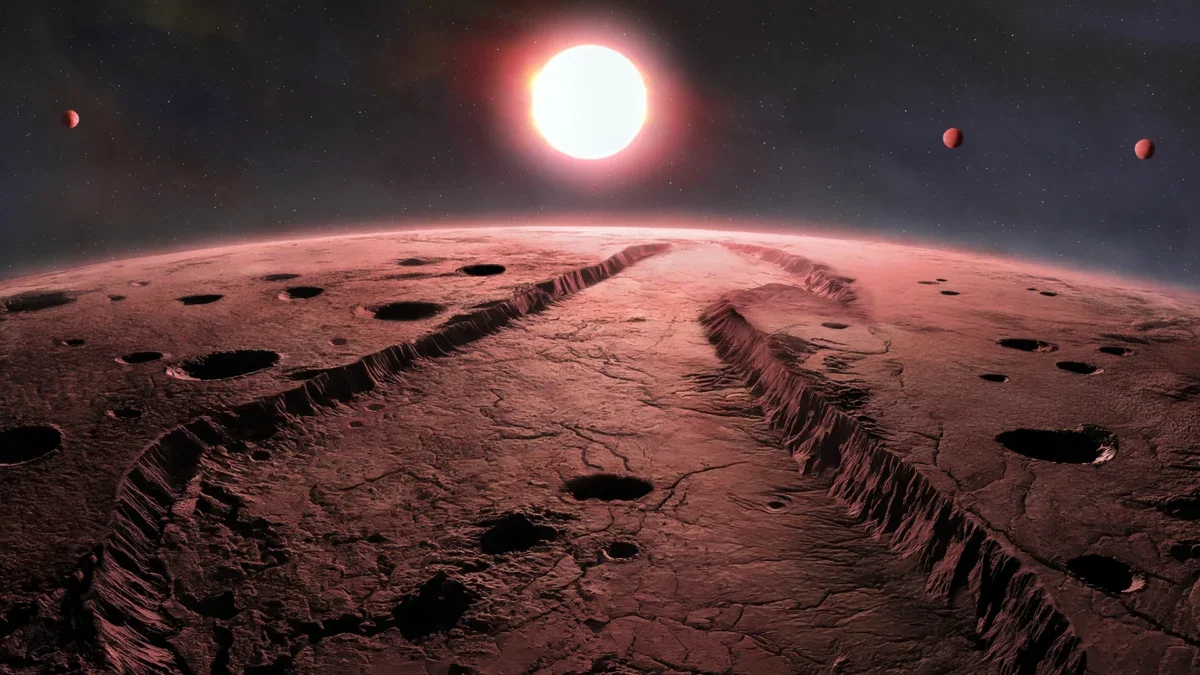

Each of the newly found planets is a smaller sub-Earth, with no more than about a third of Earth’s mass, and travels around its host star in less than seven days.

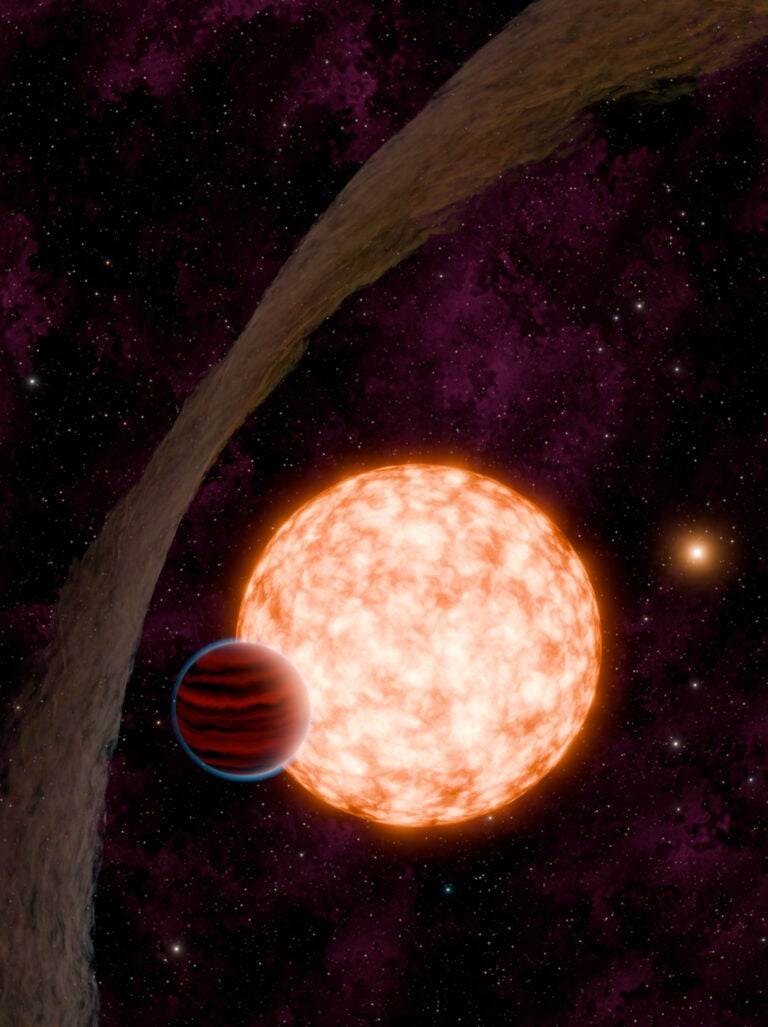

Although Barnard’s Star is a small, dim red dwarf only a little bigger than Jupiter and thus much less bright than our Sun, the four planets all orbit so closely that they are within the inner boundary of their star’s habitable zone. The habitable zone is the region around a star where temperatures allow a planet to host liquid water on its surface. So, these planets all orbit so closely that temperatures are too high for liquid surface water to remain.

The four planets are also at the mercy of their star’s bad behavior. Red dwarfs are dimmer but much more active than larger stars like the Sun. Barnard’s Star is estimated to be at least 10 billion years old and is less active than other red dwarfs, but it still suffers from occasional flare-ups of stellar activity. This includes flares in 1998 and 2019 that scientists used to deduce that planets orbiting there would have trouble holding on to their atmospheres on geological timescales.

Although the prospects of life here look dim, this discovery nonetheless shows that there are likely plenty more worlds left to find even within our own local neighborhood. Since the first exoplanet was confirmed in 1995, we have definitively found nearly 6,000 more. This number is sure to continue rising like a meteor, with amazing implications for our place in the universe.