Tianwen-1 should reach Mars in February 2021, where the spacecraft will separate and deploy a Mars-orbiting satellite, as well as a lander and rover combo.

The orbiter’s capabilities are comparable to other spacecraft already circling Mars. It packs medium and high-resolution cameras, plus radar and instruments to study Mars’ magnetism and chemical composition. But the lander/rover is the real star of the show.

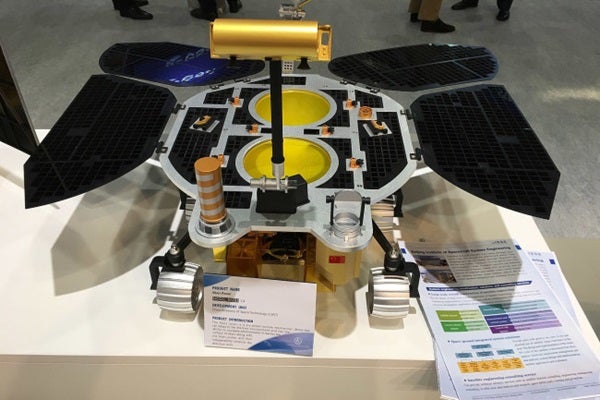

Once the lander touches down on solid ground, it will deploy a sophisticated, six-wheeled, solar-powered robotic rover. The 530-pound rover will travel across the martian surface looking for evidence of life on Mars, as well as studying the martian soil chemistry and searching for signs of past and present water.

The mission’s goals are similar to those of NASA’s latest Mars rover, dubbed Perseverance, which is also set to launch between July 30 and August 15.

However, while NASA has recently built up a track record of successful rover landings, this will be China’s maiden attempt. History hasn’t been kind to first-timers on Mars. Even after four previous successful landings, NASA engineers still refer to their rover landing sequences as “seven minutes of terror.”

Mars mission failures

The Red Planet is a notoriously hostile place to send a spacecraft.

Humanity’s first two attempts to land on Mars ended in failure. In 1971, the Soviet Union’s Mars 2 spacecraft made it all the way to the surface, only to crash land. The Mars 3 mission, following right on its heels, landed on the surface, but then failed to send back a single full image. Five years later, the U.S. made it look easy when NASA’s Viking landers successfully touched, spending years returning pioneering data.

But things haven’t always gone smooth since then. Dozens of other Mars missions have also failed. In fact, half of all missions to Mars didn’t survive. Perhaps most famously, NASA’s $327 million Mars Climate Orbiter turned into a fireball back in 1999. Why, you ask? One team of engineers used metric units and another used English units.

Fortunately, the odds of success have improved some recently, with NASA and other space agency’s deploying a string of pioneering missions. And in 2014, India put its Mars Orbiter Mission into orbit, becoming the first country to accomplish the feat on its first attempt.

But even some recent “successes” have been beset with problems. For example, NASA’s Mars InSight lander has gathered the first direct evidence of martian earthquakes, but it’s also spent over a year trying to drill more than a couple inches beneath the martian surface. The mission’s main goal is to reach a depth of some 16 feet.

Chinese rovers

Despite the historic difficulty of landing on Mars, China may have a leg up.

In the last 10 years, China has sent two rovers to the Moon. Starting back in 2002, Chinese engineers began developing a lunar rover named Yutu, which ultimately deployed in 2010 and went on to become the longest operational lunar rover in history. In 2019, they followed that success up with the Yutu-2 rover, which became the first spacecraft to softly touch down on the farside of the Moon. For the past year and a half, Yutu-2 has been uncovering new details about the ground beneath the mysterious lunar farside.

But Mars is much farther away than the Moon. Plus, it has significantly more gravity, as well as a thin-yet-noticeable atmosphere to overcome. So, it’s far harder to land on Mars than the Moon.

Thankfully for China, they don’t have to completely start from scratch. Their rover will also make use of lessons learned by NASA’s previous Mars rovers. For instance, Tianwen-1 will land using a system of parachutes, rockets and inflatable airbags similar to what NASA has employed in the past. (Due to the enormous size of NASA’s latest rovers, they now use a fascinating sky crane maneuver.)

This also isn’t China’s first attempt at reaching Mars.

In 2011, Russia and China partnered on the Phobos-Grunt mission. The spacecraft was designed to travel to Mars and land on its Moon, Phobos, then return samples back to Earth. The mission would’ve also released China’s first Mars spacecraft, the Yinghuo-1 orbiter. However, a malfunction left Phobos-Grunt — and the Chinese orbiter — stuck in Earth orbit.

This time, they hope things will be dramatically different.

Life on Mars

The rover’s timing couldn’t be better. It’s set to arrive at perhaps the most fascinating point in the history of space exploration — as astronomers, planetary scientists, and biologists all attempt to understand the martian environment.

For decades now, scientists have known that the Red Planet once held vast oceans, and possibly life. But a string of tantalizing clues have recently surfaced suggesting that Mars’ water wasn’t confined to the ancient past. Rivers and lakes existed there surprisingly recently. And in some places, it appears there’s even still liquid water tucked away beneath the surface today.

All of this makes some astronomers suspect we’ll eventually find evidence of life on Mars, whether it be past or present.

And now they have a good idea of where to look, too. Orbiting spacecraft, as well as NASA’s Curiosity rover, have started to catch whiffs of methane gas drifting up from beneath Mars’ surface in some places. On Earth, such signals can be created by microbial life.

To find out the source of the methane, space agencies will have to go to these places and collect samples. For example, NASA’s Perseverance rover will land in Jezero Crater, home to a former river delta, within days or weeks of Tianwen-1. Meanwhile, the Chinese orbiter will spend a few months surveying for an ideal place to land inside Utopia Planitia, according to mission scientists writing in Nature Astronomy.

The quest to solve Mars’ mysteries makes the name of China’s latest mission even more fitting. Tianwen comes from the title of an ancient Chinese poem, and it means “questions to heaven.”

And while Tianwen-1 and Perseverance are unlikely to definitely resolve the question of life on Mars, they both represent humanity’s most serious attempt to find an answer yet. Each space agency plans to follow up in the years ahead with missions that can go to Mars and return samples back to Earth. And, perhaps, those samples will bring us the first firm evidence of alien life.