If all the worlds in our solar system entered an Earth impersonation contest, Titan would steal the show. Sure, human visitors to Saturn’s largest moon would die instantly without supplemental oxygen and protection against the cold — a frigid -290 degrees Fahrenheit — but the similarities shouldn’t be discounted. With a rich trove of organic molecules and weather patterns resembling our own, scientists consider Titan one of the likeliest harbors for extraterrestrial life.

The problem is, it lies just short of a billion miles away.

NASA’s Cassini spacecraft did capture more than a decade of data on Titan while orbiting Saturn alongside it. And in 2026 the agency plans to launch a drone, called the Dragonfly, which will scour the moon’s surface for signs of chemical processes that could breathe life into inanimate material. That mission won’t land until 2034, however.

In the meantime, a research team led by chemists at Southern Methodist University is studying those same processes here on Earth. In the decidedly non-celestial setting of a Dallas, Texas, laboratory, they’ve created what they call Titan-in-a-test-tube: the conditions of a remote, exotic world reproduced in a tiny glass cylinder.

A familiar scene

Naturally, that’s no small task. Even Tomče Runčevski, the experiment’s principal investigator, doesn’t claim a perfect understanding of the environment. “It is incredibly difficult to mimic Titan,” he said at the fall meeting of the American Chemical Society, acknowledging that they don’t even know how many chemicals exist there. But, he added, “it’s better to start from something, and then to build on that.”

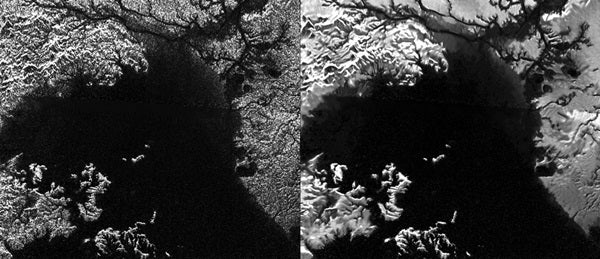

What we do know is that beneath the smoggy, orange haze that masks the world below, Titan is a wondrous place. It’s the only moon with a substantial atmosphere, which, like Earth’s, is composed mostly of nitrogen. It’s also the only other heavenly body of any kind known to sport liquid rivers, lakes and seas on its surface — though they obviously aren’t made of H2O, which freezes at temperatures well above those on Titan. “On Earth we have water,” Runčevski said. “On Titan, the same role of water is played by methane.”

These streams and pools give rise to a climate with hydrological cycles similar to the ones that sustain us. Methane evaporates from the surface, condenses in the atmosphere and rains down to refill the reservoirs from which it came. It’s a reprise of our own home planet in its early years, before these same phenomena somehow begat the world we see today. If it happened here, why not there?

Foundations of life

After replicating these features in the test tube, the researchers added two carbon-based compounds believed to be mixed in with all that methane: acetonitrile and propionitrile. Despite their status as common organic solvents, familiar to any chemist, their structures as solids are poorly understood. But Runčevski and his colleagues found that on Titan, they are typically polarized mineral crystals and could serve as templates for the assembly of other organic compounds — a gathering with the potential to generate biotic matter.

Rather than speculate on the possibility of alien life, though, Runčevski prefers to focus on demystifying its origins. “In my opinion, for now we cannot answer that question,” he said. “There is so much to be learned about the basics of what can lead to life — what is there on Titan, what was there on Earth when life started.” A better grasp of how compounds like acetonitrile and propionitrile behave under various circumstances could help with modeling prebiotic chemistry.

An improved picture of the moon’s conditions — the nature of its terrain, what chemicals are present and in what form — could also yield useful insights for the Dragonfly mission. “We’ll learn something about the next of kin to Earth, and I do believe that’s very important,” Runčevski said, reiterating that Titan may be our best bet in the search for galactic neighbors. “In order to detect that life, in order to understand it … we do need to know a little bit more about how this surface would look like.”