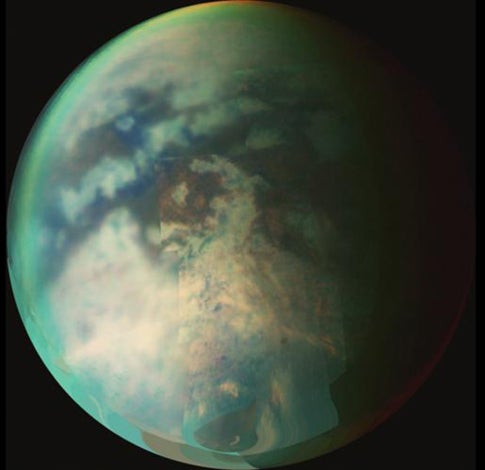

On Tuesday, scientists at the American Geophysical Union meeting in San Francisco announced significant new findings from Saturn’s moon Titan. The surprises include the moon’s largest known mountain range, which is coated with multiple layers of organic material; odd clouds that may be created like orographic clouds (those that form due to mountains) on Earth; and glimpses of a tectonic system on the moon that may explain how all these processes tie together in Titan’s history.

“We see a massive mountain range that kind of reminds me of the Sierra Nevada Mountains in the western United States,” says Bob Brown, team leader of the Cassini Visual and Infrared Mapping Spectrometer (VIMS). Brown presented his results along with Dennis L. Matson, Cassini’s project scientist, and Rosaly Lopes, Cassini radar team member.

“You have to remember that Titan is the most earthlike place in the solar system,” says Lopes, “except it’s in a deep freeze.” If Titan were Earth, the newly discovered mountains would lie south of the equator, somewhere in New Zealand. They stretch 93 miles (150 kilometers) long, are about 19 miles (30 km) wide, and probably stand about nearly a mile (1.5 km) high. The mountains are surprising, in part, because Titan’s surface is clearly an active one that is relatively young, with active erosion and other processes going on. What could have created such a mammoth chain of mountains?

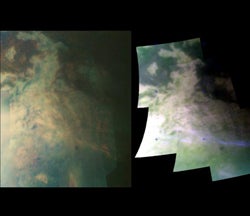

Processes that could have formed the mountains puzzled astronomers. So too did the nature of the mountains themselves. “These mountains are probably as hard as rock,” says Larry Soderblom, a Cassini team member at the U.S. Geological Survey, “made of icy materials, and are coated with different layers of organics.” Soderblom emphasizes the strange nature of what Cassini scientists know about the composition of the mountains. “There seem to be layers and layers of various coats of organic ‘paint’ on top of each other on these mountaintops,” he says, “almost like a painter laying the background on a canvas.”

Strangely, Brown and Lopes also found that weird clouds seem to form near the mountains, and “It’s difficult to explain,” says Brown, “how they do it.” After analyzing several scenarios, however, Brown feels the clouds form when methane is pushed over ridges, cools, and condenses. This produces a fog that resembles orographic clouds on Earth.

Excitingly, Brown suggests these results are giving Cassini scientists the first possibility of understanding an emerging geological picture of Titan. “Some problems require all the data from all the instruments,” he says. “But we won’t understand Titan geologically until we have data from both instruments at high resolutions.”