Key Takeaways:

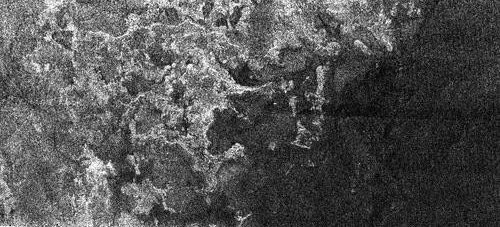

With each orbital pass by Saturn’s planet-size moon Titan, NASA’s Cassini spacecraft reveals more territory. Following the third radar-mapping pass, completed September 7, scientists are piecing together clues of a geologically active world. Beneath the thick orange fog, Cassini has charted windswept areas resembling desert sands, canyons cut by some kind of fluid, and mountains with vast flows of material.

Scientists so far have identified two types of drainage erosion on Titan. The first is a series of deeply cut channels roughly 0.6 mile (1 kilometer) across and 650 feet (200 meters) deep. These valleys are long, tracking as far as 120 miles (200 km) across the icy surface. The angular canyons have few tributaries and seem to follow faults in Titan’s crust.

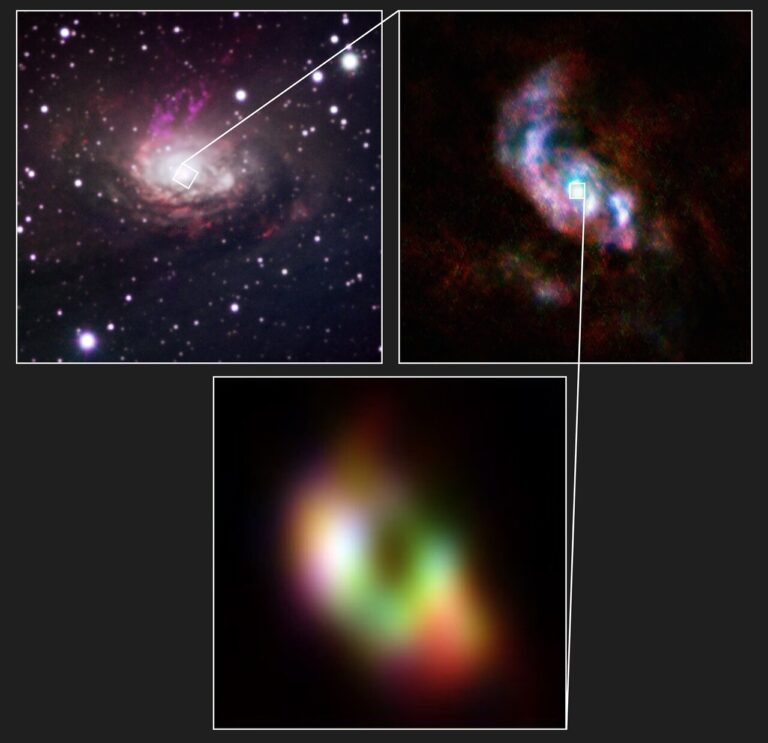

Another telltale sign of Titan’s geologic activity plays out as cryovolcanism, or ice volcanoes. Researchers note a large circular structure about 110 miles (180 km) across, provisionally called Ganesa Macula. The domed feature has radar-bright flanks radiating from a central depression. This depression could be an eroded impact crater, but Lopes believes it bears the profile of a volcanic caldera. “It definitely looks cryovolcanic. There is a dome, similar to the pancake domes on Venus, with large flows.” The flows stretch 55 miles (90 km) to the southeast, apparently transporting material along the mountain’s flanks.

Titan’s cryovolcanoes could be triggered by tidal heating — the flexing of interior material resulting from Titan’s elliptical orbit around Saturn. Along with the channels, ridges, and valley networks, Titan’s landscape bears witness to a dynamic, active world.