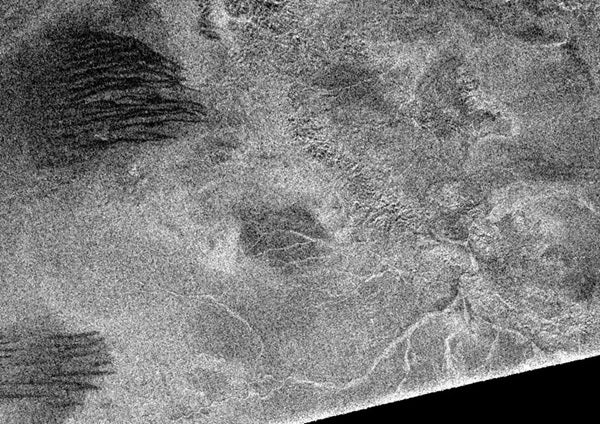

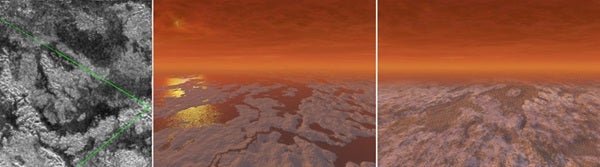

Radar images returned by the Cassini spacecraft now circling Saturn contained a surprise about the gas giant’s planet-size moon Titan: Its frozen surface is covered with dunes that rival Earth’s deserts. “We’ve been bewildered for some time by the forms we’ve seen in the Cassini data,” says Ralph Lorenz, Cassini team member at the Lunar and Planetary Laboratory in Tucson, Arizona. “The exciting thing is that we can now start to make sense of things on Titan,” he says.

Lorenz and others believe the dunes — one of the few earthlike formations seen on the bizarre moon — may consist of pulverized water ice. Titan’s surface comprises primarily water ice frozen rock-hard in Titan’s frigid temperature (–290º Fahrenheit, –179º Celsius). Titan’s ice plays the same role that stone does on Earth. Relentless winds may break down the ice into particles similar to terrestrial sand. The roughly parallel dunes spread across regions up to 930 miles (1,500 kilometers) long and are similar in form to the majority of dunes seen on Earth in sites such as Africa’s Namib Desert.

But even more alien processes may be at work, Lorenz reports in the May 5 issue of Science. A constant rain of organic material drizzles from Titan’s ruddy sky. This sooty sludge may pile up into material that is blown into the dune-like formations visible in Cassini images.

The dunes’ shapes and locations are consistent with this unique tidal wind, which may dominate the near-surface environment. “This is probably one of the neatest implications of our study,” says Lorenz. The circulation of Titan’s atmosphere may echo that of Earth’s Hadley cells, air columns that bring dry air to desert regions while circulating moist air into higher latitudes.

On Titan, any moisture is in the form of liquid methane. Titan’s chilly temperature holds methane to a consistency of thin gasoline. If a Hadley cell-like dynamic is present on Titan, researchers may see more dune-covered areas across Titan’s equatorial region. Nearer the poles, liquid methane may pool into ponds, flowing rivers, or even vast lakes. Future Cassini passes will image higher latitudes. With Cassini’s continued return of rich data, it may be a simple matter of time before scientists decode this mystery.