Data collected during several recent flybys of Titan by NASA’s Cassini spacecraft provide supporting evidence to scientists who think the saturnian moon contains active cryovolcanoes spewing a super-chilled liquid into its atmosphere.

“Cryovolcanoes are some of the most intriguing features in the solar system,” said Rosaly Lopes, a Cassini radar team investigation scientist from NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) in Pasadena, California.

Rather than erupting molten rock, it is theorized that the cryovolcanoes of Titan would erupt volatiles such as water, ammonia, and methane. Scientists have suspected cryovolcanoes might inhabit Titan, and the Cassini mission has collected data on several previous passes of the moon that suggest their existence. Imagery of the moon includes a suspect haze hovering over flow-like surface formations. Scientists point to these as signs of cryovolcanism.

“Cassini data have raised the possibility that Titan’s surface is active,” said Jonathan Lunine, a Cassini interdisciplinary scientist from the Lunar and Planetary Laboratory, University of Arizona, Tucson. “This is based on evidence that changes have occurred on the surface of Titan, between flybys of Cassini, in regions where radar images suggest a kind of volcanism has taken place.”

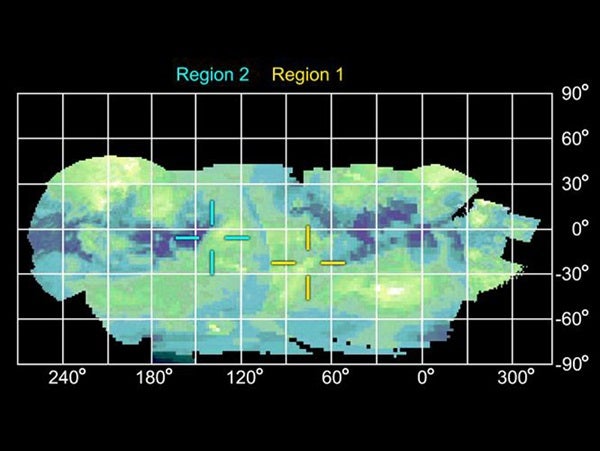

What led some Cassini scientists to believe that things are happening now were changes in brightness and reflectance detected at two distinct regions of Titan. Reflectance is the ratio of light that radiates onto a surface to the amount reflected back. These changes were documented by Visible and Infrared Mapping Spectrometer data collected on Titan flybys from July 2004 to March 2006. In one of the two regions, the reflectance of the surface surged upward and remained higher than expected. In the other region, the reflectance shot up but then trended downward. There is also evidence that ammonia frost is present at one of the two changing sites. The ammonia was evident only at times when the region was inferred to be active.

“Ammonia is widely believed to be present only beneath the surface of Titan,” said Robert M. Nelson of JPL, a scientist for Cassini’s Visual and Infrared Mapping Spectrometer team. “The fact that we found it appearing at times when the surface brightened strongly suggests that material was being transported from Titan’s interior to its surface.”

Some Cassini scientists indicate that such volcanism could release methane from Titan’s interior, which explains Titan’s seemingly continuous supply of fresh methane. Without replenishment, scientists say, Titan’s original atmospheric methane should have been exhausted long ago.

But other scientists familiar with the spectrometer data argue that the ammonia identification is not certain, and that the purported brightness changes might not be associated with changes on Titan’s surface. Instead they might result from the transient appearances of ground “fogs” of ethane droplets very near Titan’s surface, driven by atmospheric rather than geophysical processes. Nelson has considered the ground fog option, stating, “There remains the possibility that the effect is caused by a local fog, but, if so, we would expect it to change in size over time due to wind activity, which is not what we see.”

An alternative hypothesis to an active Titan suggests the saturnian moon could be taking its landform evolution cues from a moon of Jupiter.

“Like Callisto, Titan may have formed as a relatively cold body, and may have never undergone enough tidal heating for volcanism to occur,” said Jeffrey Moore, a planetary geologist at the NASA Ames Research Center, Moffett Field, California. “The flow-like features we see on the surface may just be icy debris that has been lubricated by methane rain and transported down slope into sinuous piles like mudflows.”