(Inside Science) — I was born and raised in Hong Kong — the Pearl of the Orient. It’s one of the most vibrant cities in the world and is famous for its neon-lit night markets. I also did not see the Milky Way until I was 30, when I visited Monument Valley in the Navajo Nation.

There, I felt a visceral appreciation in being able to see the night sky the way humanity had seen it for millennia, and I wished I could’ve experienced it without having to undertake the multiday road trip. While it may be difficult to convert the collective feeling of loss of my fellow city kids into a dollar amount, light pollution can also harm human health, waste money, and disrupt ecosystems.

But it is also important for us to have lights.

Electric lights have enabled adults to work and party and children to learn and play past sundown. Lights in our neighborhoods make us feel safe, lights on the roads help us see where we’re going at night, and lights in our offices, factories, shops, restaurants and warehouses bolster a nighttime economy that has become an integral part of our cities.

We clearly need light in our modern society, but we may have gone overboard. And compared with toxic chemicals in our water and air, light pollution may seem less tangible as a threat.

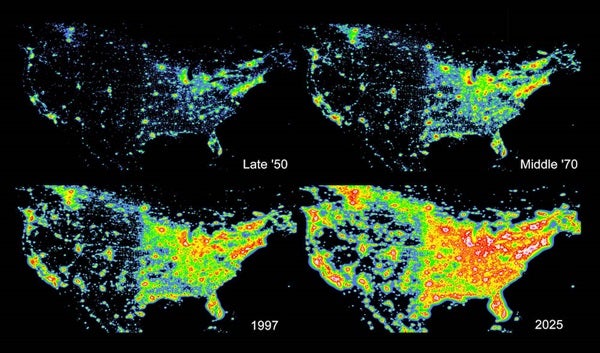

“I feel that light pollution [regulation] is basically 60 years behind where air pollution [regulation] is. Think about before the Clean Air Act, when there were very few regulations for what you can release into the air,” said Daniel Mendoza, the co-director of the Consortium of Dark Sky Studies at the University of Utah in Salt Lake City.

If we want more people to experience the magic of a dark sky close to home, we’ll have to think more carefully about how we use artificial light. What benefits does light give us? What harms does it do? And how can we be smarter about the ways we use light to maximize the benefit while minimizing the brightness?

Public safety

“Sunlight is said to be the best of disinfectants; electric light the most efficient policeman,” wrote Louis Brandeis, a former U.S. Supreme Court justice, in 1933.

“The fear of crime due to darkness is something that’s as old as civilization. They had oil-based streetlamps in ancient Rome. It’s not a new idea,” said Aaron Chalfin, a criminologist from the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia.

This fear of crime is perhaps more than just a feeling; according to Chalfin, there is evidence supporting the intuition.

“There have been a few papers that looked at the changeover to daylight savings time. Basically, all of a sudden, it’s dark outside when it used to be bright just a day ago, or vice versa, and they find that certain crimes, like robbery and auto vehicle theft, can be quite sensitive to lighting conditions,” said Chalfin.

A separate study led by Chalfin and his colleagues also found evidence that supports the idea of darker streets leading to more crime. The researchers looked at a six-month period in public housing developments in New York City and noticed a significant reduction in certain types of crime for areas that received extra lighting.

However, these findings don’t necessarily mean we should install as many lights on as many streets as possible. For one thing, with limited public funding, there may be other more cost-effective ways to deter crime. It is also possible for streetlights to only shift crime to different areas within the city or to a different time without reducing crime overall. These factors must be considered as part of the ongoing conversation regarding policing and the equity of public safety.

Moreover, said Chalfin, while there is reasonably good evidence that lighting conditions can affect crime in the short term, there is a lot more uncertainty about longer-term effects.

There is also the question of whether the results of these studies can be generalized, or whether they differ from city to city. Indeed, some studies find no safety benefits from lighting.

“We did some research for the National Institute for Health Research [in the U.K.] to find out whether there was any evidence that reducing street lighting was associated with any increase in crime or road traffic crashes, and we found no evidence that it was,” said Phil Edwards, a population health statistician from the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine in the U.K.

When you consider other factors related to crime, such as income, education, gang presence, and even the local weather, it is difficult to generalize and quantify the long-term impact of street lighting on crime.

But even though the data is inconclusive, one thing is clear: We, as humans, have a shared fear of the dark.

Monsters in the dark

People often want more lighting not because some studies have shown that lighting reduces crime, but because lighting makes them feel safer, said Chalfin.

Most of us have probably experienced a fear of the dark. Some evolutionary biologists have linked this fear to the fear of predators from a time when humans were not on top of the food chain. And this innate anxiety, difficult to quantify with numbers, probably plays a part in the lack of public will to get rid of street lighting.

“You have to take into account the views of the communities,” said Edwards. Without the support of the public, changes are simply not possible. Because ultimately, scientists don’t plan cities — government officials, often elected by the people, do.

“In the U.K., there are people who are very vocal about this, and they would say things like ‘How dare you turn the lights out? We’re paying our [taxes]!’ There was even an opposition [when a local township was planning on reducing street lighting] where the community got together and said ‘Look, we’ll pay more — how much more do we need to pay to keep our lights on?'” said Edwards.

While people may struggle to change their preferences about street lighting in their local neighborhood, there are other sources of light pollution, such as those along highways and in industrial and commercial buildings, that may be easier to curtail.

Blinded by the lights

In 2012, the Federal Highway Administration, under the U.S. Department of Transportation, published an update to the 1978 handbook for road lighting design. The update included considerations for the negative impact of excessive lighting, while the older approach mainly focused on recommending the minimal lighting requirements — for example, the minimum lighting needed for a stretch of road leading up to an intersection, given the speed limit and the curvature of the road.

So, what does the data say about the correlation between accidents and streetlamps on highways?

In 1992, the International Commission on Illumination, a nonprofit organization headquartered in Vienna, Austria, published a report that examined 62 studies of lighting and road accidents from 15 countries. While 85% of the studies claimed their data showed lighting to be beneficial in preventing nighttime accidents, only about one-third showed statistical significance. Among that one-third, the reported accident reduction ranged widely, from 13 percent to as much as 75 percent.

How is this huge discrepancy possible? Can’t one just set up an experiment with two identical roads, one with light and one without, and compare the numbers?

In addition to logistical difficulties and ethical concerns for such an experiment, the light versus no-light way of thinking is perhaps itself a false dichotomy, since the efficacy of street lighting depends on how the lights are set up.

“Here’s an example: Say you’re driving on the highway at night, and someone behind you turns on their brights. It flashes on your rearview mirror and you get temporarily blinded,” said Mendoza. “The intention is to have appropriate lighting, and that we are not discussing or arguing for removal of all lighting.”

There are instances where reduced lighting can actually improve its intended functionality.

“Sometimes you have a bright streetlight, and then 30 meters down the road is another one, but there is kind of a ‘light trough’ in between where it is much darker and your eyes can’t see,” he said. “If we dimmed these lights, these troughs would appear less deep, and your eyes can see better.”

There are also other sources of light besides streetlamps lining our roads, some of which probably do more harm than good when it comes to preventing accidents.

“One of the biggest hazards is electronic billboards, as they are sparsely regulated, if at all. Some of them don’t even have a night mode, meaning they are as bright at night as they are during the day when they are competing with the sun,” said Mendoza. These billboards can be especially dangerous, say, when they display a blindingly white advertisement right after one with a darker color scheme. “They are a huge distraction that could be really dangerous.”

Sleepless bright nights

Speaking of distractions, lighting at night can also affect sleep and human health.

While people may be most aware of the effects of looking at smartphones and TV screens at night, outdoor lighting can also invade people’s bedrooms. Growing up, I remember being able to read my comic books using the streetlight shining through my bedroom window, long after my mom had turned out the light and told me to go to bed.

Researchers have noticed the effect this modern way of living may have on our bodies, most notably through the disruption of our circadian rhythm.

“Although it is difficult to prove whether artificial light can harm you directly — it’s not as straightforward as something like smoking, for example — what it does is it alters your circadian rhythm, which can lead to a wide range of health problems,” said Mendoza.

For one thing, people with disrupted circadian rhythms often don’t get enough sleep. In 2014, the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention declared sleep deprivation to be a “public health epidemic,” and some researchers consider it to be a rising global epidemic. Lack of sleep has been linked to a variety of health problems, ranging from relatively unsurprising ones such as depression to certain forms of cancer and even Alzheimer’s.

“Currently, that’s how a lot of people view the world. If you’re going to a city, you expect it to be all lit up at night. There’s an expectation in the public that good governance is about lighting up the streets at night. So, turning the lights off is seen by some people as regressing and stepping back,” said Edwards, the public health expert from the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine. “That is probably something that needs to change.”

Dead birds and baby turtles

Humans aren’t the only species affected by artificial lights.

“I believe that we can have vibrant cities and dark skies, but we need to understand the multiplicity of the problem, to understand who the stakeholders are. And not only the ones who are speaking out loud, but also the passive stakeholders, including animals and vegetation,” said Vellachi Ganesan, a lighting designer from the University of Utah in Salt Lake City.

Audiences of the BBC’s Planet Earth II may remember the harrowing scene where baby sea turtles mistake city lights for moonlight and crawl into oncoming traffic or fall into storm drains.

The disruption of bird migration is another problem. According to a study published in 2017, the Sept. 11 memorial light in Manhattan — which has been turned on only one night a year — affected the behavior of about 1 million birds over a seven-year span.

“If we know the specific times when certain types of birds migrate through an area, then we can ask ourselves: How many businesses need to have lighting turned on at night during those times? Maybe it’s harder for an area with a lot of restaurants and pubs, but what about other areas?” said Ganesan. “We can have a smart system where certain buildings would turn off their lights at a certain time, or parking lots with the lighting level set at 20 percent until someone drives into them.”

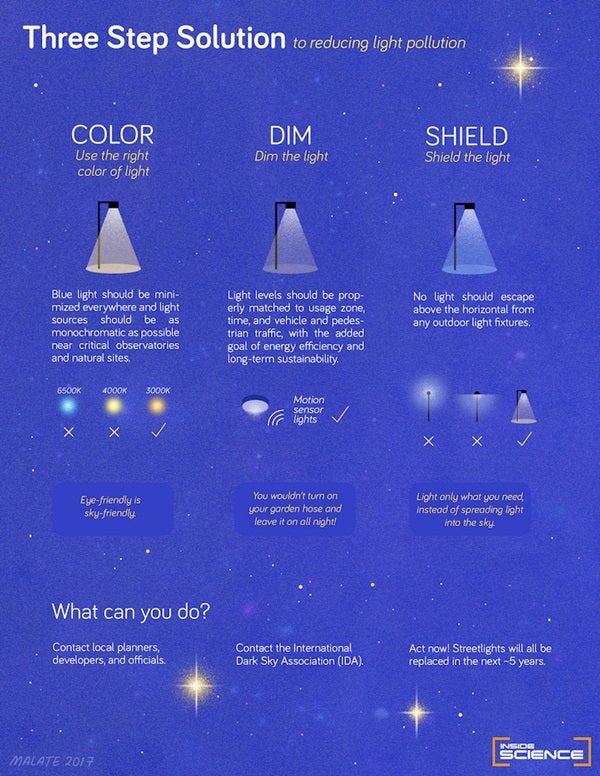

The best solutions to light pollution are not necessarily about the overall amount of light, but what is “the right light in the right place at the right time,” said Edwards.

And better lighting design can save more than birds and sea turtles — it saves money too.

Money to be made

“It’s estimated that in the U.S., every year, there’s about 1.2 to 1.8 billion dollars’ worth of wasted electricity from poorly pointed light. That’s just light that basically goes up towards the sky and doesn’t illuminate anything, or lighting that is unnecessary,” said Mendoza.

According to Edwards, in the U.K., there have been local municipalities where lights are turned off at midnight and back on at 5 am. “And the local authorities were able to say that they were saving hundreds of thousands of pounds in energy costs just by reducing street lighting,” said Edwards. “You also have to consider the amount of coal that is being burnt just to keep those lights on all night every night in every city — that’s a hell of a lot of carbon dioxide.”

Some communities have even turned having a dark sky into a money-making business opportunity.

“For instance, Utah has embraced astrotourism as one of its economic strategies, and now people would come from all over the U.S. to see the Milky Way. Because that has proven to be a viable economic strategy, we’re seeing more and more places trying to get certified as dark sky places,” said Ganesan.

“But we do have to be careful, and not say things like ‘You must get rid of all lights’ or ‘We have to live in the dark forever.’ We’ll have to try to educate people and to promote the evidence and the science for better lighting,” she said.

Unlike most environmental pollution, light pollution is not a byproduct of technology. The light, the product that we want, is the pollutant itself. Because of this, the only way to mitigate light pollution is to reduce and better manage the way we use light.

This story was originally published on Inside Science. Read the original here.