The field of exoplanet discovery and research has veritably exploded in recent years, as our ability to find ever-smaller, more Earth-like planets around fellow Milky Way stars — and even, in rare cases, other galaxies altogether. With the Kepler telescope running out of fuel, now is the perfect time for TESS to step into the transiting planet detection scene, helping to grow our catalog of nearby planets immensely in preparation for the launch of the James Webb Space Telescope, now anticipated to occur in 2020.

You can find a more in-depth look at TESS in our July 2017 issue, or check out our free downloadable eBook, Our search for extrasolar planets, to learn more. Below is the TESS roundtable discussion, courtesy of The Kavli Foundation.

A NEW ERA IN THE SEARCH FOR EXOPLANETS—and the alien life they might host—has begun. Aboard a SpaceX rocket, the Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite (TESS) launched on April 18, 2018, at 6:51 PM EDT. The TESS mission, developed with support from The Kavli Foundation, is led by the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) and the MIT Kavli Institute for Astrophysics and Space Research.

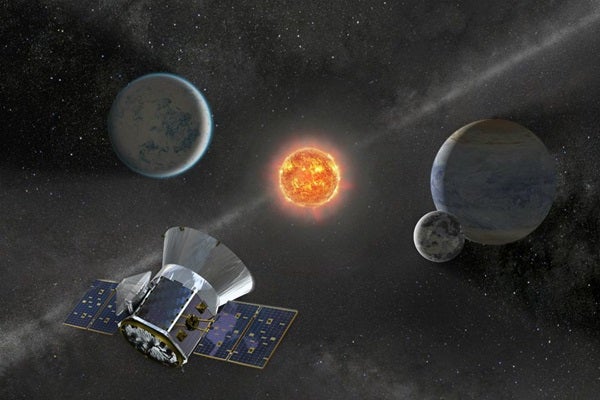

Over the next two years, TESS will scan the 200,000 or so nearest and brightest stars to Earth for telltale dimming caused when exoplanets cross their stars’ faces. Among the thousands of new worlds TESS is expected to discover should be hundreds ranging in size from about one to two times Earth. These small, mostly rocky planets will serve as prime targets for detailed follow-up observations by other telescopes in space and on the ground.

The goal for those telescopes will be to characterize the newfound exoplanets’ atmospheres. The particular mixtures of gases in an atmosphere will reveal key clues about a world’s climate, history, and if it might even be hospitable to life.

The Kavli Foundation spoke with two scientists on the TESS mission to get an inside look at its development and revolutionary science aim of finding the first “Earth twin” in the universe.

The participants were:

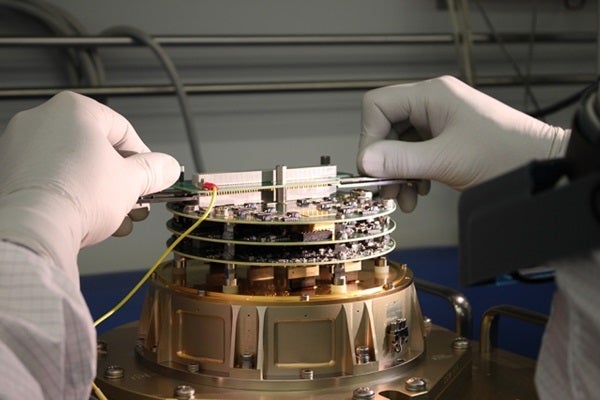

- GREG BERTHIAUME – is the Instrument Manager for the TESS mission, in charge of ensuring the spacecraft’s cameras and other equipment will perform their science tasks. Berthiaume is based at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology’s (MIT) Lincoln Laboratory and he is also a member of the MIT Kavli Institute for Astrophysics and Space Research.

- DIANA DRAGOMIR – is an observational astronomer whose focus is on small exoplanets. Dragomir is a Hubble Postdoctoral Fellow at the MIT Kavli Institute for Astrophysics and Space Research.

The following is an edited transcript of their roundtable discussion. The participants have been provided the opportunity to amend or edit their remarks.

THE KAVLI FOUNDATION: Starting with the big picture, why is TESS important?

DIANA DRAGOMIR: TESS is going to find thousands of exoplanets, which might not sound like a big deal, because we already know of nearly 4,000. But most of those discovered planets are too far away for us to do anything more than just know their size and that they are there. The difference is that TESS will be looking for planets around stars very close to us. When stars are closer to us, they’re also brighter from our point of view, and that helps us discover and study the planets around them much more easily.

GREG BERTHIAUME: One of the things TESS is doing is helping to answer the fundamental question, “Is there other life in the universe?” People have been wondering that for thousands of years. Now TESS won’t answer that question directly, but it’s a step, just like Diana mentioned, on the path to getting us the data to see where there might be other life out there. That’s something we’ve been struggling with and questioning since we were able to come up with questions.

DRAGOMIR: TESS will probably find 100 to 200 approximately Earth-size worlds, as well as thousands of more exoplanets all the way up to Jupiter in size.

BERTHIAUME: We’re trying to find planets that are Earth analogs, meaning they’ll be Earth-like in their characteristics, such as size, mass, and so on. That means we want to find planets with atmospheres, with gravity similar to Earth’s. We want to find planets that are cool enough so water can be liquid on their surfaces, and not so cold that the water is frozen all the time. We call these “Goldilocks” planets, located in a star’s “habitable zone.” That’s really our target.

DRAGOMIR: Exactly right. We want to find the first “Earth twin.” TESS will mainly find planets in the habitable zone of red dwarfs. These are stars a bit smaller and cooler than the Sun. A planet around a red dwarf can be located in an orbit closer to its star than it could be with a hotter star like our Sun and still maintain that nice, Goldilocks temperature. Closer orbits translate to more transits, or star crossings, which makes these red dwarf planets easier to find and study than planets around Sun-like stars.

Astronomers are working hard on ways that we might push the TESS data and find some planets in the habitable zone of Sun-like stars, too. It’s challenging because those planets have longer orbital periods—years, that is—than close-in planets. That means we need a lot more observation time in order to detect enough transits of the planets across their stars to say we’ve definitely detected a planet. But we’re hopeful, so stay tuned!

“One of the things TESS is doing is helping to answer the fundamental question, ‘Is there other life in the universe?'”—Greg Berthiaume

TKF: What do you need to see in order to deem any of the planets discovered by TESS as potentially habitable?

|

| TESS will discover thousands of exoplanets in orbit around the brightest stars in the sky. This first-ever spaceborne all-sky transit survey will identify planets ranging from Earth-sized to gas giants, around a wide range of stellar types and orbital distances. No ground-based survey can achieve this feat. NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center/CI Lab

|

DRAGOMIR: We want a planet to be close to Earth in size for all the reasons we just gave, but there’s a small problem with that. Those sorts of planets will probably have pretty small atmospheres, compared to how much rock makes up their bulk. And for most telescopes to be able to look at an atmosphere in detail, we actually need the planet to have a substantial atmosphere.

This is because of a technique we use called transmission spectroscopy. It gathers the light from the star that has gone through the atmosphere of the planet when the planet is crossing the star. That light comes to us with a spectrum of the planet’s atmosphere imprinted on it, which we can analyze to identify the composition of the atmosphere. The more atmosphere there is, the more material there is that can imprint on the spectrum, giving us a bigger signal.

If the light from the star is going through very little atmosphere, though, like we’d be looking at with an Earth twin, the signal would be very small. Based on what TESS finds, we’re therefore going to be starting with bigger planets that have a lot of atmosphere, and as we get better instruments, we’re going to move towards smaller and smaller planets with less atmosphere. It’s those latter planets which will more likely be habitable.

BERTHIAUME: What we’re going to look for in the atmosphere are things like water vapor, oxygen, carbon dioxide—the standard gases we see in our atmosphere that life needs and life produces. We’re also going to try and measure the nasty things that aren’t compatible with life as we know it on Earth. For instance, it would be a bad thing for biology if there were too much ammonia in a world’s atmosphere. Hydrocarbons, like methane, would also be problematic in too high an abundance.

TKF: Diana, your specialty is exoplanets smaller than Neptune—a planet four times bigger than Earth. What is our general knowledge about those kinds of worlds and how will TESS help with your research?

DRAGOMIR: One thing we know about these planets is that they are extremely common compared to planets larger than Neptune. So that’s good. We therefore expect TESS to find lots and lots of planets smaller than Neptune for us to look at.

Although small is bad for getting those atmospheric imprints we just talked about, if the stars are nearby and bright, we might still be able to get enough light for doing good studies. I’m hoping that we’ll get enough below Neptune-size that we’ll start looking at the atmospheres of “super-Earths,” which are planets twice the size of Earth or so. We don’t have any super-Earths in our solar system, so we’d love to get a closer look at one of these kinds of worlds. And just maybe, if we find a really, really good planetary candidate, we may be able to start looking at the atmosphere of an Earth-sized planet.

With my research, one more thing TESS could really help with is figuring out the boundary between a very gassy planet like Neptune and a very rocky planet like Earth. We believe it’s mostly a matter of mass; have too much mass, and the planet stars to hold into a thick atmosphere. Right now, we’re not sure where that threshold is. And that matters so we know when a planet is rocky and potentially habitable, or gassy and not habitable.

BERTHIAUME: My job as instrument manager is different from a science job, for sure. My job was to make sure that all of the pieces, all the parts that go into the four flight cameras and the image processing hardware all play and work together and give us the great data that we need for Diana to go and continue to explore exoplanets. My personal role on the mission actually ends shortly after launch. Once we’ve demonstrated that the satellite provides the data that we expect, and we deal with any surprises that may come up, then I move on and data goes off to the science community.

I definitely feel responsible for getting the quality of the data as high as it possibly can be. A lot of people worked really hard for years to build the cameras that are flying on TESS and it’s been great to be part of that team.

TKF: New exoplanet missions like the European Space Agency’s Ariel and Plato satellites are slated to begin in the late 2020s. How might these future spacecraft complement and build on TESS’ body of work?

DRAGOMIR: The great thing about TESS is that it’s going to give us a lot to choose from in terms of the best options for planets we’ll want to study. In that way, TESS will set the stage for Ariel’s mission, which is to deeply study the atmospheres of a select group of exoplanets.

The Plato mission will be looking for planets that are habitable, but around bigger stars like the Sun, whereas TESS will focus on looking for habitable planets around smaller stars. I’m happy with that because I don’t want us to put all of our eggs in one basket by only looking at red dwarf stars with TESS. Planets around these red dwarfs are very exciting right now because they’re easier to study and they transit their stars more often, making them easier to find. But at the same time, red dwarfs tend to be much more active than the Sun. When a star is active, that means it often expels bursts of radiation called flares. These flares could be very damaging to a planet’s atmosphere and make the world uninhabitable.

In the end, we of course live around a Sun-like star, and so far, we are the only “we” we know of in the universe. So for those reasons, it’s great to have Plato complementarily come along and find those planets around suns that TESS will probably not be able to find.

“The great thing about TESS is that it’s going to give us a lot to choose from in terms of the best options for planets we’ll want to study.”—Diana Dragomir

TKF: When do you expect TESS’ first discoveries of brand new worlds to be reported?

BERTHIAUME: First, it’s going to take a while to get TESS into its unique orbit. It’s the first time we’re putting a spacecraft in a new kind of far-ranging, highly elliptical orbit, where the gravity from the Earth and the Moon will keep TESS very stable, both from an orbit perspective and from a thermal perspective. So a big part of what’s going to happen over the first six weeks is just achieving that final orbit.

Then there’s a period of time where there’ll be data collected to make sure the instruments are working as expected, as well as getting our data processing pipeline tuned up. I think we’ll start to see interesting results come out sometime this summer.

DRAGOMIR: Because TESS is observing so much of the sky, it’s going to see lots of things that are happening in real-time, not just exoplanets crossing stars. As for those stars, we can learn a lot about their properties and even measure their masses quite precisely by doing asteroseismology with TESS. This technique involves tracking brightness changes as sound waves move through the interiors of stars—just like how seismic waves pass through the Earth’s rock and molten insides during earthquakes.

We’ll also be studying the flaring activity of the stars, which as we spoke about earlier might make close-in, temperate planets around red dwarf stars uninhabitable.

Moving up in size, scientists will want to search the TESS data for evidence of small black holes. These extreme objects, formed when colossal stars explode, can orbit normal stars that are still “alive,” so to speak. These systems will help us better understand how those black holes form and how they interact with companion stars.

And then finally, going even bigger, TESS will look at galaxies called quasars. These ultra-bright galaxies are powered by supermassive black holes in their cores. TESS will help us monitor how quasars’ brightness changes, which we can link back to the dynamics of their black holes.

TKF: The James Webb Space Telescope, hailed as the successor to the Hubble Space Telescope, has long been talked about as a primary instrument for doing the detailed follow-up observations on promising exoplanets found by TESS. However, James Webb’s launch, already delayed multiple times, just got pushed out yet another year, to 2020. How will the ongoing James Webb delays affect the TESS mission?

DRAGOMIR: The James Webb delay is not so much of a problem because it actually gives us more time to collect great target planets with TESS. Before we can use James Webb to really observe candidate exoplanets and study their atmospheres, we first need to confirm the planets are real—that what we think are planets are not false positives caused, for instance, by stellar activity. That confirmation process takes weeks, using support observations from ground-based telescopes. It will then also take weeks to months to obtain the mass of the planets. We measure that by registering how much planets cause their host stars to experience slight “wobbles” in their motion over time, owing to the planets’ gravities, which are determined by their mass.

Once you have that mass, plus the size of an exoplanet based on how much starlight it blocks during a TESS detection, you can measure its density and determine if it’s rocky or gaseous. With this information, it is then easier to decide which planets we want to prioritize, and the more we can make sense out of what James Webb will tell us about their atmospheres.

TKF: Spacecraft sometimes have humorous or even profound extra elements built into them. One example: the “Golden Records” on the twin Voyager spacecraft, which contain images and sounds of life and civilization on Earth, including the Taj Mahal and birdsong. Are there any such items included on TESS? Any subtle maker’s marks or messages?

BERTHIAUME: One of the things that’s flying along with TESS is a metal plaque that has the signatures of many of the people who worked on developing and building the spacecraft. That was an exciting thing for us.

DRAGOMIR: That’s cool. I didn’t know that!

BERTHIAUME: Also, NASA ran an international contest inviting people from around the world to submit drawings of what they thought exoplanets might look like. I know many children participated. All of those drawings were scanned onto a thumb drive and they’re flying along with TESS. The spacecraft’s orbit is stable for a century at least, so the plaque and the drawings will be in space for a long time!

—Adam Hadhazy, Spring 2018