But September’s star attraction lies closer to home. The Moon takes center stage three times during its monthly tour of the sky. In the first act, Earth’s satellite passes in front of 1st-magnitude Aldebaran before dawn September 5. Observers along a line that runs from the western shore of Lake Superior to Florida’s east coast will see the star emerge from behind the Last Quarter Moon’s dark limb as the pair rises. The farther north and east of this line you live, the higher the two objects will appear. From New York City, for example, they stand 11° above the eastern horizon when Aldebaran returns to view at 12:40 a.m. EDT.

The Moon passes in front of a much bigger and brighter star September 13. The target this time is the Sun, and Luna obscures part of it for people in southern Africa, southern Madagascar, and parts of the Indian Ocean and Antarctica. The best sites on land for this partial solar eclipse are around Cape Town, South Africa, where the event starts shortly before sunrise and peaks at 5h43m UT. The Moon then blocks 30 percent of the Sun’s surface area.

The Moon’s final and most impressive act arrives the night of September 27/28 when it dives deep into Earth’s shadow to create a spectacular total lunar eclipse. Observers across most of North America will see all 72 minutes of totality the evening of the 27th. Viewers in most of Europe, Africa, and the Middle East will witness the eclipse before dawn on the 28th. (See “Eclipse of the Super Moon” on p. 56 for complete details.)

In contrast to lunar events timed in minutes or hours, planets typically remain on display for weeks or months. Case in point: Mercury, which hangs low in the west after sunset during September’s first half. The planet reaches greatest elongation September 4, when it lies 27° east of the Sun. Although that sounds pretty impressive, Mercury remains a horizon hugger for Northern Hemisphere observers. The ecliptic — the Sun’s apparent path across the sky that the planets follow closely — makes a shallow angle to the western horizon after sunset around the autumnal equinox. Most of Mercury’s elongation translates into distance along the horizon and not altitude above it.

Saturn is a much more attractive target for evening observers. The ringed planet stands nearly 20° above the southwestern horizon as darkness falls in mid-September and doesn’t set until 10 p.m. local daylight time. A waxing crescent Moon points the way September 18 when it passes 3° north of Saturn.

At magnitude 0.6, the planet stands out against the backdrop of eastern Libra. Saturn’s only rival in this area is magnitude 1.1 Antares, located 12° to the southeast in neighboring Scorpius.

The ringed world appears best through a telescope when it lies higher in the sky during the early evening hours. Any instrument will show the planet’s 16″-diameter globe surrounded by a ring system that spans 37″ and tilts 24° to our line of sight.

You also should see Titan in proximity to Saturn. This 8th-magnitude moon passes due north of the planet September 7 and 23 and due south on the 15th. A trio of 10th-magnitude satellites — Tethys, Dione, and Rhea — orbit closer in and show up through 4-inch and larger scopes.

Remote and mysterious since its discovery 85 years ago, Pluto remains distant but is far less enigmatic thanks to the eagle-eyed sensors aboard NASA’s New Horizons spacecraft. Experienced observers can spy the magnitude 14.2 dwarf planet north of the Teapot asterism in Sagittarius through an 8-inch or larger telescope. Fortunately, magnitude 3.5 Xi2 (ξ2) Sagittarii lies nearby. Pluto spends September between 0.6° and 0.7° west of this star. Sketch or photograph the area, and return to it a few nights later. The “star” that moved is Pluto.

The ice giant world lies roughly midway between 4th-magnitude Lambda (λ) and 5th-magnitude Sigma (σ) Aquarii. Don’t confuse Neptune with a nearby magnitude 6.9 star in early September. On the 4th, the planet slides 3.6′ due north of this star. A telescope will help confirm Neptune’s identity. Under moderate magnification and steady seeing, you’ll see its 2.4″-diameter disk and blue-gray color.

As Neptune climbs higher in the southeastern sky, Uranus appears low in the east. The seventh planet, which will reach opposition in mid-October, trails about two hours behind its more distant cousin. Uranus resides in a faint part of Pisces (although, let’s face it, all of Pisces is faint), in the same binocular field as magnitude 5.2 Zeta (ζ) Piscium. You will find Zeta 17° east-southeast of Algenib (Gamma [γ] Pegasi), the star that forms the southeastern corner of the Great Square of Pegasus.

Once you locate Zeta through binoculars, Uranus should be a snap. On September 1, the planet lies 0.5° (the diameter of a Full Moon) due south of Zeta and about half that distance west-northwest of 88 Psc, a magnitude 6.0 star. Uranus shines at an intermediate magnitude of 5.7. The planet’s westward motion relative to the starry background during September carries it to a position 1.2° southwest of Zeta by month’s end.

If you target Uranus through a telescope, you’ll immediately notice its non-stellar appearance. The world’s disk spans 3.7″ and has an obvious blue-green hue.

Fortunately, the ecliptic stands nearly straight up from the eastern horizon before dawn at this time of year, so angular distance from the Sun translates into altitude. How much difference does this make? Consider that Mercury lies 27° east of the Sun at greatest elongation September 4 but appears only 3° high a half-hour after sunset. On the same day, Venus stands 28° west of the Sun and climbs 16° above the eastern horizon 30 minutes before sunrise.

The beginning of September finds Venus in southern Cancer and Mars 9° to its north. A waning crescent Moon passes between the two worlds on the 10th; Jupiter adds to the spectacle when it rises an hour before the Sun.

Venus crosses from Cancer into Leo on September 24, coincidentally the same day Mars passes 0.8° due north of the Lion’s luminary, 1st-magnitude Regulus. The Red Planet shines at magnitude 1.8 and offers a lovely color contrast with the slightly brighter blue-white star. Jupiter gleams at magnitude –1.7 just 10° below Mars. The gap between these two worlds tightens in late September; the pair will meet in mid-October.

The stunning naked-eye and binocular views of the three planets will garner lots of attention, but it’s also worth targeting Venus through a telescope. On the 1st, its beautiful 9-percent-lit crescent measures 52″ from cusp to cusp. By month’s end, the planet’s diameter shrinks to 33″ and the Sun illuminates 34 percent of the disk.

Although Mars is too small (4″ across) to show appreciable detail through a telescope, Jupiter spans a more impressive 31″. You’ll have a narrow window of visibility between the time it rises and the onset of bright twilight to view its dynamic cloud tops and four bright moons.

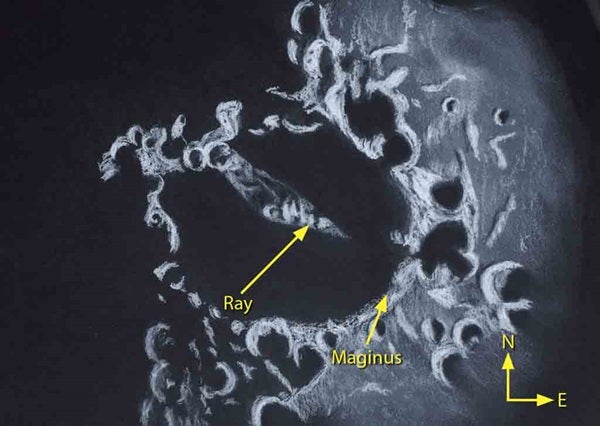

There should be a ray of hope (OK, sunshine) spreading across the floor of the battered crater Maginus on the evening of September 20. This 100-mile-wide impact feature sports a bulged-up floor, central mountain peaks, and a low rim. The last attribute is the most critical for the crater’s appearance on the 20th because it allows a prominent V-shaped splay of sunlight to reach across the otherwise dark floor.

Like so many events in astronomy, timing is everything when it comes to seeing this ray. On the evening before, Maginus remains in complete darkness; by the evening after, the Sun has risen high enough to illuminate nearly the entire crater. For the best viewing, you might have to wait until late evening when the Moon dips low in the west. See “Catch some Moon rays” in the July Astronomy for more examples of sunrise and sunset rays.

Don’t confuse the Maginus ray with the much more common ejecta rays best seen around Full Moon. The latter formed when large, relatively recent impacts excavated lighter-hued material and dispersed this debris in streaks across the Moon’s face. The most spectacular ejecta rays spread from Maginus’ northern neighbor, Tycho.

Maginus lies deep in the Moon’s southern hemisphere at a latitude of –50°. It appears closer to the lunar limb than you might expect, however, thanks to the foreshortening effect of the globe curving away from us. For the same reason, circular craters near the limb appear oval.

By the time Full Moon — and a total eclipse — arrives September 27, the Sun lies high in the lunar sky and shadows have disappeared. All that remains of Maginus are subtle features for patient selenophiles.

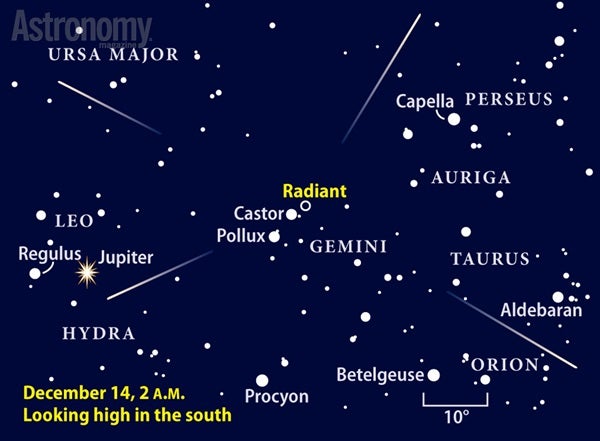

Because only a half dozen or so major meteor showers occur each year, observers often have to make due with minor events. That is the case in September. The best bet is the Epsilon Perseids, which burst on the scene with a slew of bright meteors in 2008 and delivered a similar display in 2013. In other years, however, the rate tops out at five meteors per hour.

The “shooting stars” appear to radiate from a point in Perseus near 2nd-magnitude Algol. For North American observers, the peak arrives the evening of September 9, though Perseus climbs highest just before dawn. A thin waning crescent Moon, which rises around 4 a.m. local daylight time, won’t interfere at all.

| WHEN TO VIEW THE PLANETS |

||

| Evening Sky |

Midnight | Morning Sky |

| Mercury (west) |

Uranus (southeast) |

Venus (east) |

| Saturn (southwest) |

Neptune (south) |

Mars (east) |

| Neptune (southeast) |

Jupiter (east) |

|

| |

Uranus (southwest) |

|

| |

||

Let’s piggyback on the excitement stemming from the Rosetta spacecraft’s ongoing encounter with Comet 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko by looking at the icy visitor with our own eyes. City and suburban lights will overwhelm the comet’s fuzzy glow, so you’ll need to observe under a dark sky. The object climbs highest in the east shortly before dawn. The best observing window opens as the waning Moon exits the morning sky around September 10 and lasts about two weeks.

Comets are notorious tricksters, even those like 67P that have returned to the inner solar system several times. Astronomers offer a wide range of predictions on how bright it will be, from a dim magnitude 10.5 to a feeble magnitude 13.5. If we’re on the lucky side of these estimates, an 8-inch scope will pick it up nicely; if not, you’ll need a 12-inch or larger instrument. In a final, ironic twist, we view the comet’s dusty tail through the veil of debris left behind by countless other comets. Known as the zodiacal band, this soft glow envelops the path of the planets where 67P resides.

On September 10, you can find the comet 1° south of 6th-magnitude Lambda (λ) Cancri. The pair lies almost directly above the stunning conjunction of the crescent Moon and Venus. A week later, 67P passes 2° north of the Beehive star cluster (M44). Closest approach occurs the mornings of September 16 and 17. The 5th-magnitude star Gamma (γ) Cancri lies 0.4° south of the comet on the 17th.

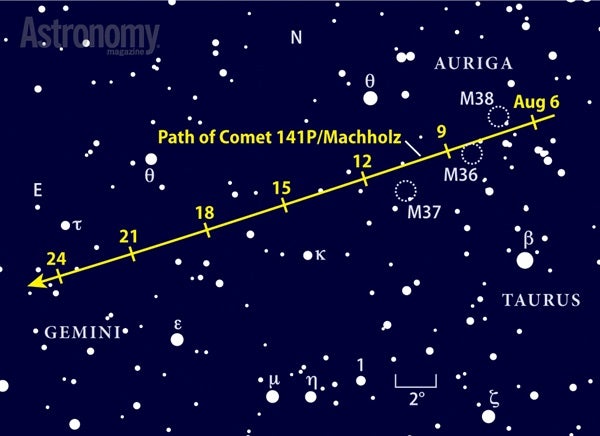

There’s a slim possibility that 67P could get upstaged by Comet 141P/Machholz if the latter ends its life with a major flare-up. Coincidentally, this dissolving ball of ice and dust is traveling in the same area of sky. The two comets cross paths September 1 when less than 1° separates them. Unfortunately, the Moon is just past Full phase then, making any visual observation a challenge even with Luna on the opposite side of the sky.

Typically, the farther out in the solar system an object lies, the more leisurely it moves relative to the background stars. Because orbital motion slows dramatically in the outer reaches of our planetary system, it’s rare to see a nearby object trudge along at an outer body’s pace. But that’s exactly what seems to happen in September when asteroid 1 Ceres (275 million miles from the Sun) traverses the same amount of sky as Uranus (1.86 billion miles away). Ceres still orbits the Sun at a faster speed than its cousin, but our line of sight from Earth makes the asteroid navigate a loop that extends barely 1°.

The upshot is that Ceres remains in the same field of view through a typical 4- or 6-inch telescope at low power. It lies in a sparse region of Sagittarius some 20° east of that constellation’s Teapot asterism. The best time for hunting the asteroid is midevening, when the Archer climbs highest in the south.

Ceres fades from magnitude 8.2 to 8.7 during September. You’ll find two noticeably brighter stars in the field — magnitude 7.1 SAO 211624 and magnitude 7.4 SAO 211729. Sketch the five or six brightest stars, and then come back a few nights later to locate the object that moved slightly — this is Ceres. The task is easiest around September 16 and 17 when the asteroid passes a nearly identical 8th-magnitude background star.

Martin Ratcliffe provides planetarium development for Sky-Skan, Inc. from his home in Wichita, Kansas. Meteorologist Alister Ling works for Environment Canada in Edmonton, Alberta.